George H. Williams was a Democratic politician and officeholder in Oregon from the mid-1850s to the early twentieth century. He was chief justice of the territorial supreme court, a delegate to Oregon’s constitutional convention, U.S. senator from Oregon, the first Oregonian to serve in a presidential cabinet, a member of national and international diplomatic commissions, and mayor of Portland. For his service and serenity, the Oregonian referred to him as “Oregon’s Grand Old Man.” He was, Oregonian editor Harvey Scott remarked, “a man who never lost his equipoise, nor even studied or posed to produce sensational or startling effects.”

Born in Lebanon, New York, on March 26, 1823, Williams was educated in public and private schools and read at law in Pompey Hill, New York, learning from an established Whig lawyer. In 1844, he became a lawyer and removed to Iowa, where he was elected judge, serving from 1847 to 1852. He also purchased a newspaper, the Lee County Democrat (later the Iowa Statesman), owning it until 1852.

Williams was active as a Democrat in state politics and was known as a practical politician who avoided partisanship. He became friends with Iowa’s U.S. senators, George Jones and Augustus Dodge, and attracted attention from Stephen A. Douglas, a powerful senator from Illinois. Williams had campaigned for Franklin Pierce in 1852 and was a presidential elector; and with strong support from Douglas, Pierce rewarded Williams with appointment as chief justice of the Oregon Territory Supreme Court in 1853.

Williams arrived in Oregon by steamship from San Francisco on July 2, 1853, accompanied by his wife Kate. On the territorial court, he held circuit in the Willamette Valley, based in Salem, while Matthew Deady was judge for southern Oregon Territory and Cyrus Olney served the northern territory. The first major case Williams heard was Holmes v. Ford (1853), which raised the issue of slavery. Williams ruled that slavery was not legal in Oregon, considering that the territorial legislature had not expressly legalized it. In Vandorf v. Otis (1854), he ruled that an Indian wife had legal claim to half of a 640-acre claim made by herself and her husband under the Oregon Donation Land Law.

During his first decade in Oregon, Williams became president of the Willamette Woolen Company in 1856, a trustee of Willamette University the same year, and an investor in the Oregon Printing and Publishing Company in 1863. Although he was a strong Democrat, he kept at a distance from the Salem Clique Democrats who led the party in Oregon Territory. Nonetheless, one witness reported that he was “a forcible orator” and physical, “his arms going up and down with a regular tilt-hammer motion which earned him the uneuphonious but significant soubriquet of ‘Old Flax Break.’”

In 1857, Williams was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and played an important role in framing the state constitution by publishing his “Free State Letter” in the July 28 Oregon Statesman, in which he argued against both slavery in Oregon and the residency of free Blacks. His position was based on his practical approach to politics. He was anti-slavery, but he never made a speech castigating the institution as immoral. Nonetheless, pro-slavery Democrats criticized him, but as he said years later, “I knew what I was doing. It was the only argument I could make to the people.”

Williams left the territorial bench in 1859, went into private practice with A. C. Gibbs in Portland, and actively supported the Union during the Civil War. He abandoned the Democratic Party as unpatriotic and became a Republican. The Oregon Senate selected him as a U.S. senator in 1864. He wrote the first Reconstruction Act and the Tenure of Office Act in 1867, which led to the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson in 1868. Williams voted to convict Johnson in the Senate trial.

When U. S. Grant became president, Williams was a vocal supporter and trusted adviser. Grant selected him for membership of the Joint High Commission in 1871 to resolve conflicts with Great Britain over Civil War claims, and in December of that year he appointed him attorney general of the United States. Williams prosecuted cases against the Ku Klux Klan for two years, increasing convictions of Klansmen fourfold.

Grant nominated him as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in early December 1873, but he met fierce resistance from the legal establishment because Williams lacked sufficient judicial experience and had mixed government funds with his private accounts—actions that did not rise to illegality but stained his reputation. Several key senators and Oregon politicians, including J. W. Nesmith and Henry Corbett, forced Grant to ask Williams to withdraw his candidacy in January 1874. The controversy damaged Williams’ standing sufficiently that Grant pressed Williams to resign as U.S. Attorney General in April 1875.

Williams returned to Oregon in 1881 as a partner in a private law practice. In 1901, as a reformist-minded politician, he stood as president of the Direct Democracy League, which worked to expand participation in Portland’s electoral politics. In 1902, under a new city charter, Williams ran for mayor on a reformist ticket and won, becoming reportedly the oldest mayor in the nation. His tenure was during the Lewis and Clark Exposition, a time of civic exuberance, but his administration was plagued by police corruption and his failure to stem gambling and prostitution. A grand jury indicted him in January 1905 for failing to order police to close gambling halls, but the county district attorney dismissed the charge. Williams lost his bid for re-election in 1905 to Harry Lane.

Williams was married twice, first to Kate Antwerp in Iowa in 1850 (she died in 1863) and second to Kate George in Oregon in 1867. He had one child by his first marriage and adopted two children during his second. Williams died on April 4, 1910.

-

![]()

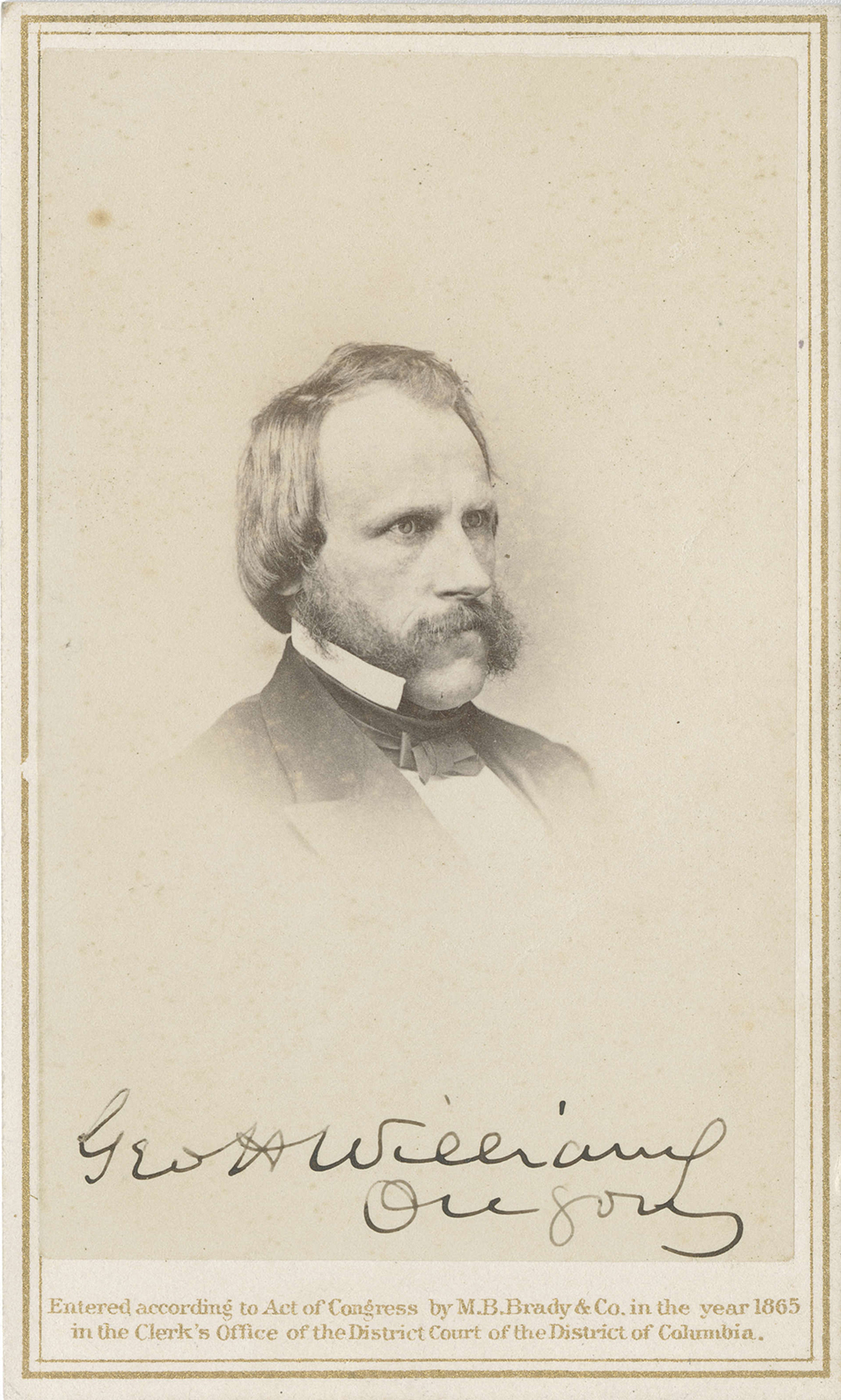

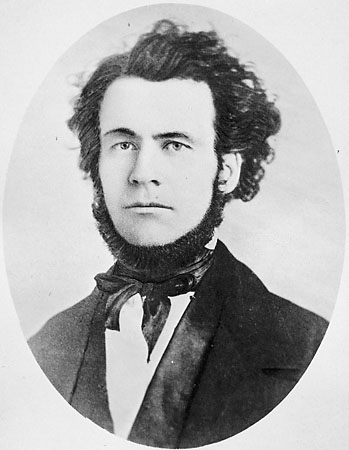

George H. Williams, 1865.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_1122_A_1 -

![]()

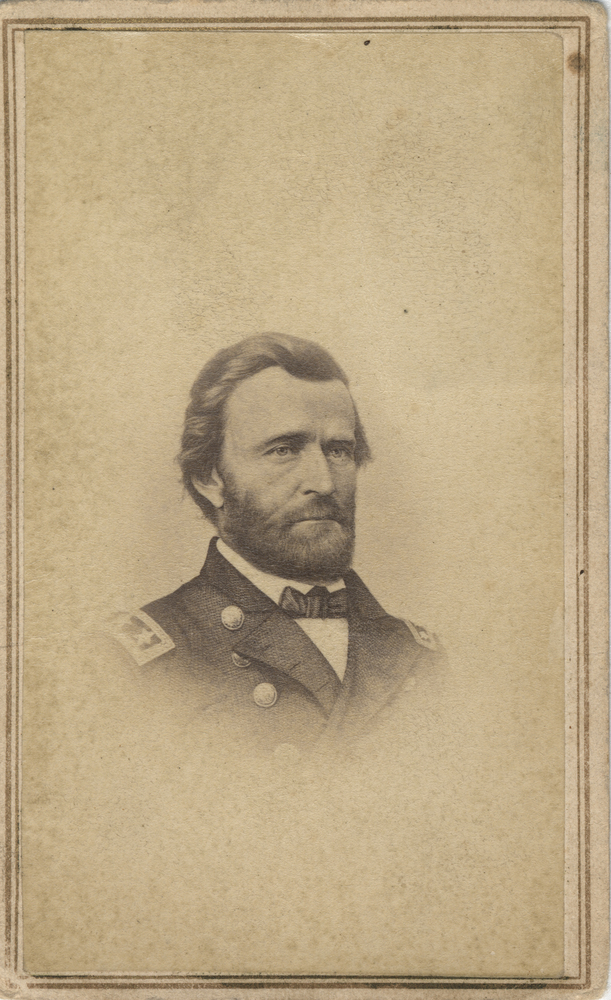

George H. Williams.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_1122_A_2 -

![]()

Kate George Williams, 1895.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi13413

-

![]()

House of Judge Williams, NW 18th and Couch, Portland.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Orhi68433

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Henry W. Corbett (1827-1903)]()

Henry W. Corbett (1827-1903)

In early 1851, Henry W. Corbett, an ambitious, twenty-four-year-old adv…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

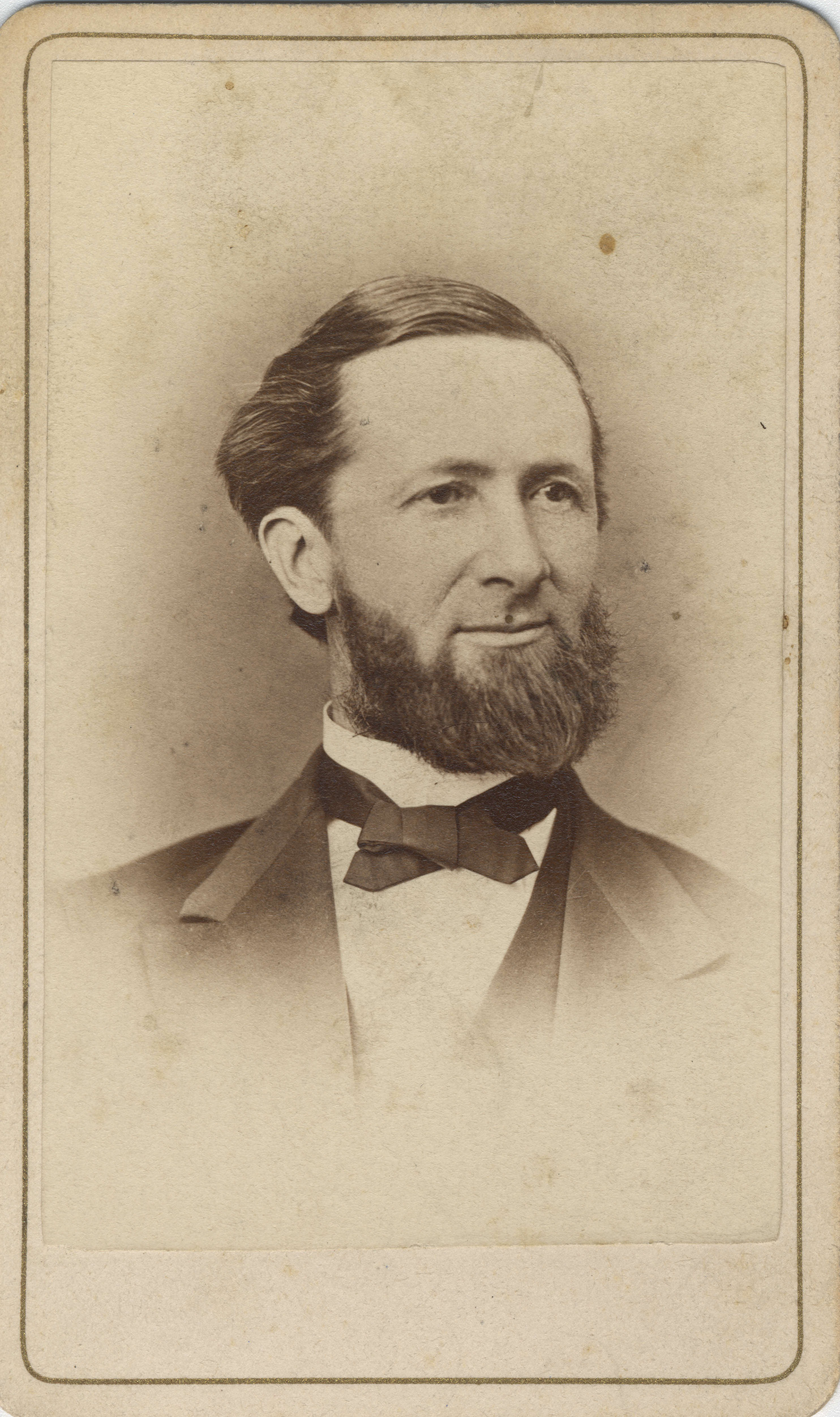

![James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)]()

James Willis Nesmith (1820–1885)

James Nesmith was a prominent figure in the Oregon Territory and in Ore…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Matthew Deady (1824-1893)]()

Matthew Deady (1824-1893)

Matthew Paul Deady was a lawyer, politician, and judge in the Oregon Te…

-

![Salem Clique]()

Salem Clique

Thomas Dryer, the first editor of the Oregonian, named the Salem Clique…

-

![Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)]()

Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)

Ulysses S. Grant, a native of Ohio, graduated from the U.S. Military Ac…

-

![United States v. Tom (1853)]()

United States v. Tom (1853)

In United States v. Tom, the Oregon Territorial Supreme Court questione…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Johnson, David Alan. Founding the Far West: California, Oregon and Nevada, 1840-1890. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992: 148-149.

Teiser, Sidney. “Life of George H. Williams: Almost Chief-Justice, part one.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 47.3 (September 1946): 255-258.

Scott, Harvey W. “An Estimate and the Character and Services of Judge George H. Williams.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (June 1910): 223.

Williams, George H. “Political History of Oregon from 1853 to 1865.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 2.1 (March 1901): 1-35.

Woodward, W.C. The Rise and Early of Political Parties in Oregon, 1843 to 1868. Portland, Ore.: J.K. Gill, 1913.