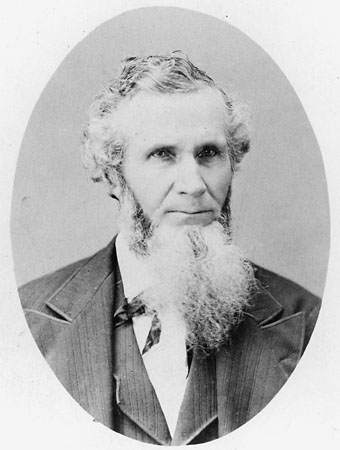

Although his time spent in Oregon was short, General John E. Wool was arguably the most important U.S. military officer to affect relations between Native and non-Native people in the Pacific Northwest. As commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of the Pacific from 1854 to 1857, the violet-eyed disciplinarian materially supported the federal government’s expansion of tribal relocation to reservations.

Born in Newburgh, New York, in February 1784, John Wool worked for a merchant at age twelve and later studied law until the outbreak of the War of 1812, when he organized and led a company of volunteer soldiers. Energetic and ambitious, he advanced to the rank of colonel and was appointed inspector general of the army in 1816. He held the position for twenty-five years, visiting forts and assessing military preparedness in the United States and Europe and actively reorganizing and innovating the antebellum army.

In 1836, Wool coordinated the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation under the Treaty of New Echota. A stickler for the letter of the law, he sought to persuade the Cherokee to relocate and instituted policies to protect Cherokee lives, property, and treaty rights. He drew the ire of Southern state authorities, who obtained his reassignment, but not before a court of inquiry had launched his image—not entirely warranted—as a humanitarian sympathetic to Native people. Promoted to brigadier general in 1841, Wool distinguished himself as a field commander during the Mexican American War and emerged a national hero. As a result, he was mentioned as a possible Democratic presidential candidate in 1852; he continued to harbor presidential ambitions into 1856.

Wool was transferred to the West in early 1854, when Secretary of War Jefferson Davis assigned him to command the Department of the Pacific, headquartered in San Francisco and later in Benicia. In California, he worked to control filibuster expeditions and vigilance committees, but his priorities soon changed. Encouraged by gold discoveries and treaties that relocated Native people to reservations and extinguished their land titles, white miners and settlers surged into northern Washington Territory and southern Oregon’s Rogue River region. Many used violence to gain access to Native lands, triggering retaliation from tribes and, in some cases, all-out war. By late 1855, the warfare in the Pacific Northwest had Wool’s attention.

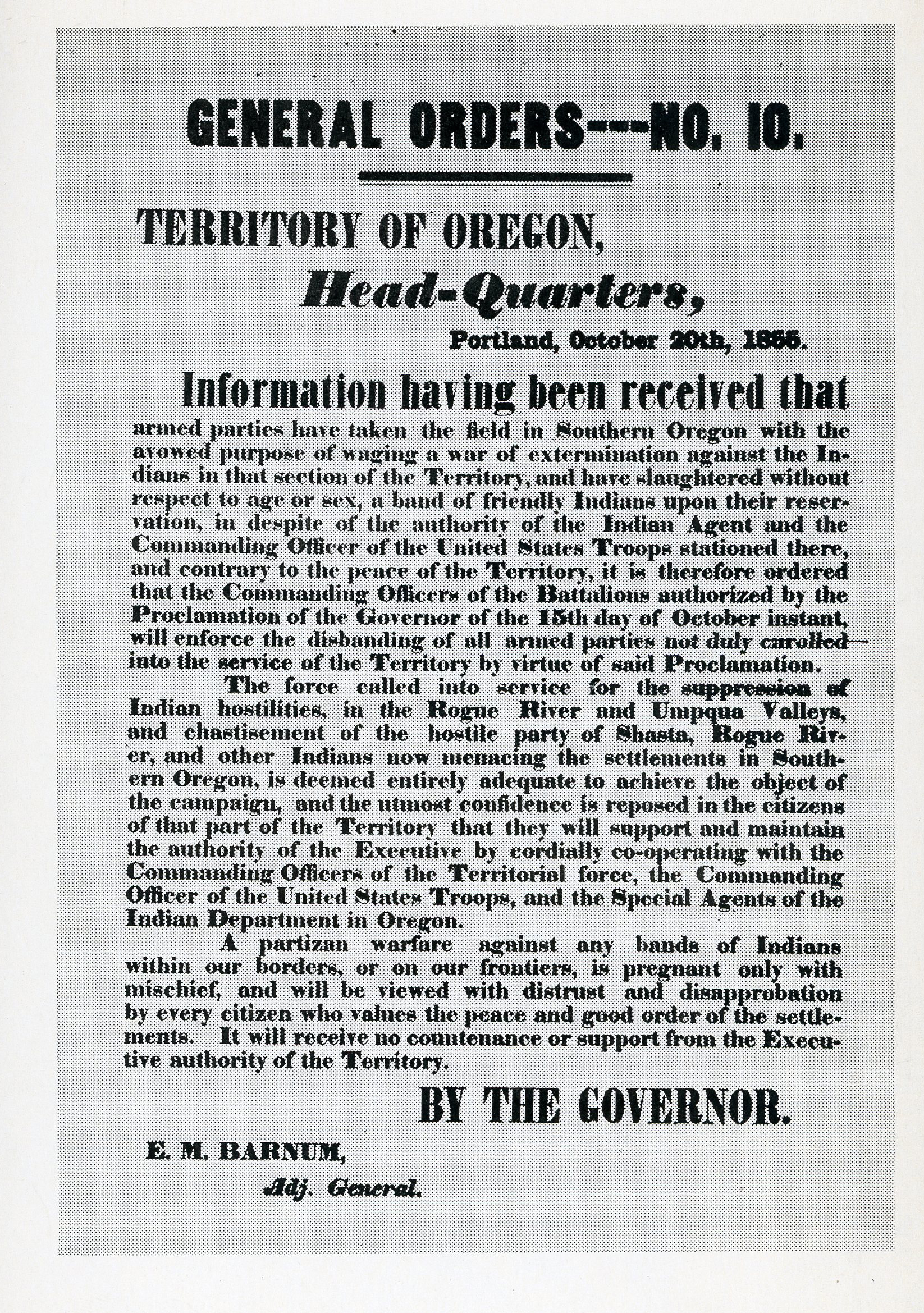

Wool arrived at Fort Vancouver in mid-November 1855 and stayed for two months, including time in Portland. He assessed federal army resources and planned a spring campaign, but he refused requests for support from territorial volunteer units already in the field, citing a lack of authority over them. This angered Isaac Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, and George Law Curry, governor of Oregon Territory, and resulted in nationwide newspaper coverage pitting Wool against the two governors in a clash between military and civil authority. A growing number of citizens and legislators charged that Wool had refused to send federal troops to the aid of volunteer soldiers and citizens, that he denied requests from the volunteers for arms and ammunition, and that his mind was, as the New York Times opined, “more on the Presidential chair than the protection of Oregon and Washington Territories.” Oregon’s legislative assembly sent a scathing memorial to President Franklin Pierce requesting Wool’s removal, as did Curry.

The tenor of Wool’s pronouncements overshadowed his public explanations: that he had strategically deployed the few troops at his command and did not require the assistance of volunteers; that for logistical reasons he planned a spring 1856 campaign to relocate tribes; and that he did not have the authority to issue arms and ammunition to civilians. Wool’s attribution of blame for the aggressions and atrocities committed by miners and volunteer soldiers—gathered from reports of the Indian Department and subordinate officers in the field—proved correct, but his decision to publicly defend his actions and to criticize the motivations of territorial citizens gave ammunition to opponents of federal Indian policy.

Wool also drew criticism for prioritizing the region’s limited military resources in Washington Territory rather than in southern Oregon. “If Gen. Wool does not send out forces to protect the citizens of Rogue River Valley,” the Oregon Argus wrote, “he deserves to have his wool taken from the top of his cocoanut.” Wool explained: “As soon as the war is terminated east of the Cascade Mountains I will be able to send all my disposable forces against the Indians on Rogue river and Puget Sound.” Returning to Fort Vancouver by steamer in March 1856, he stopped at Fort Humboldt in northern California and crafted a three-pronged Rogue River campaign for his regular army units that culminated in the Battle of Big Meadows.

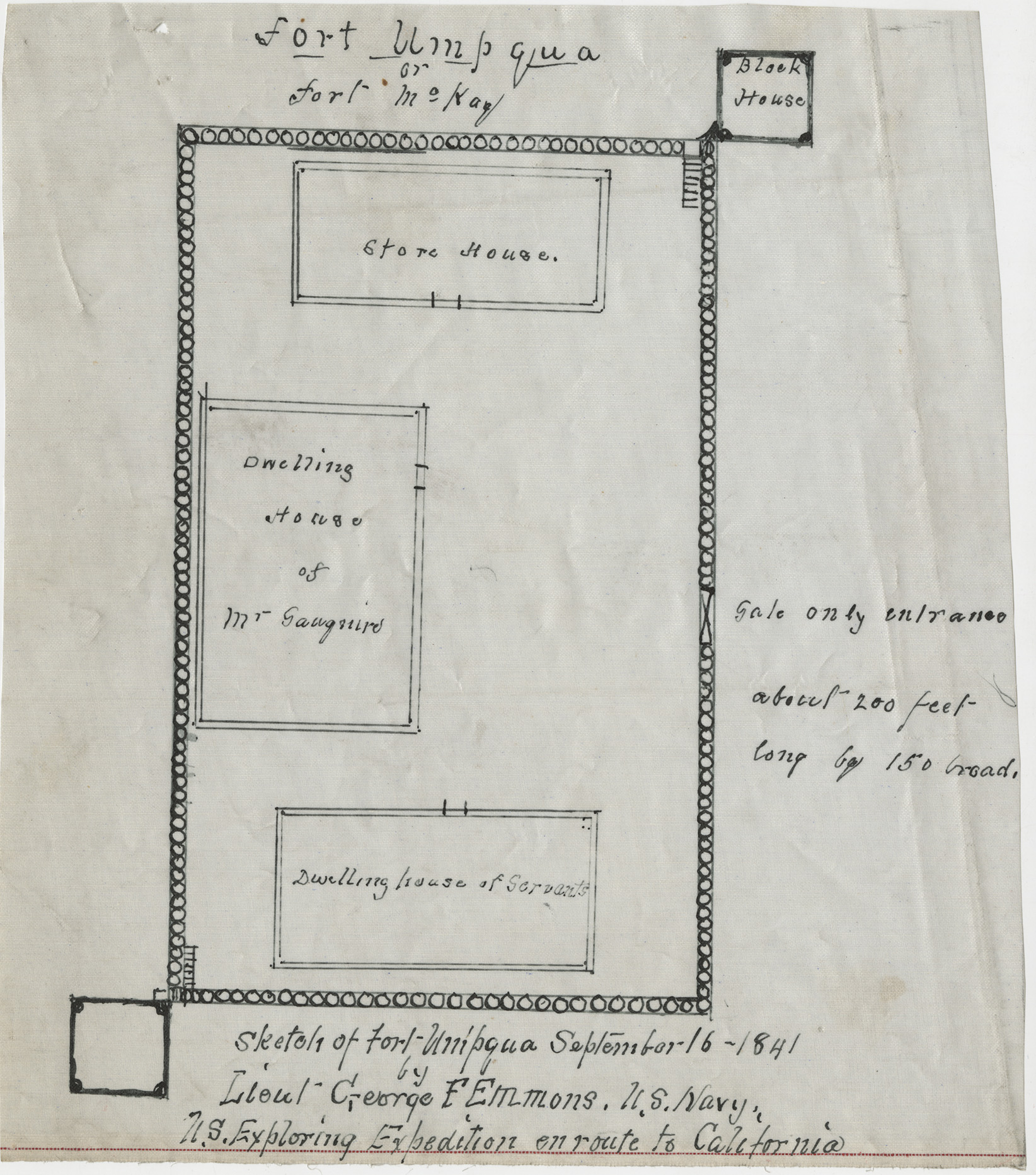

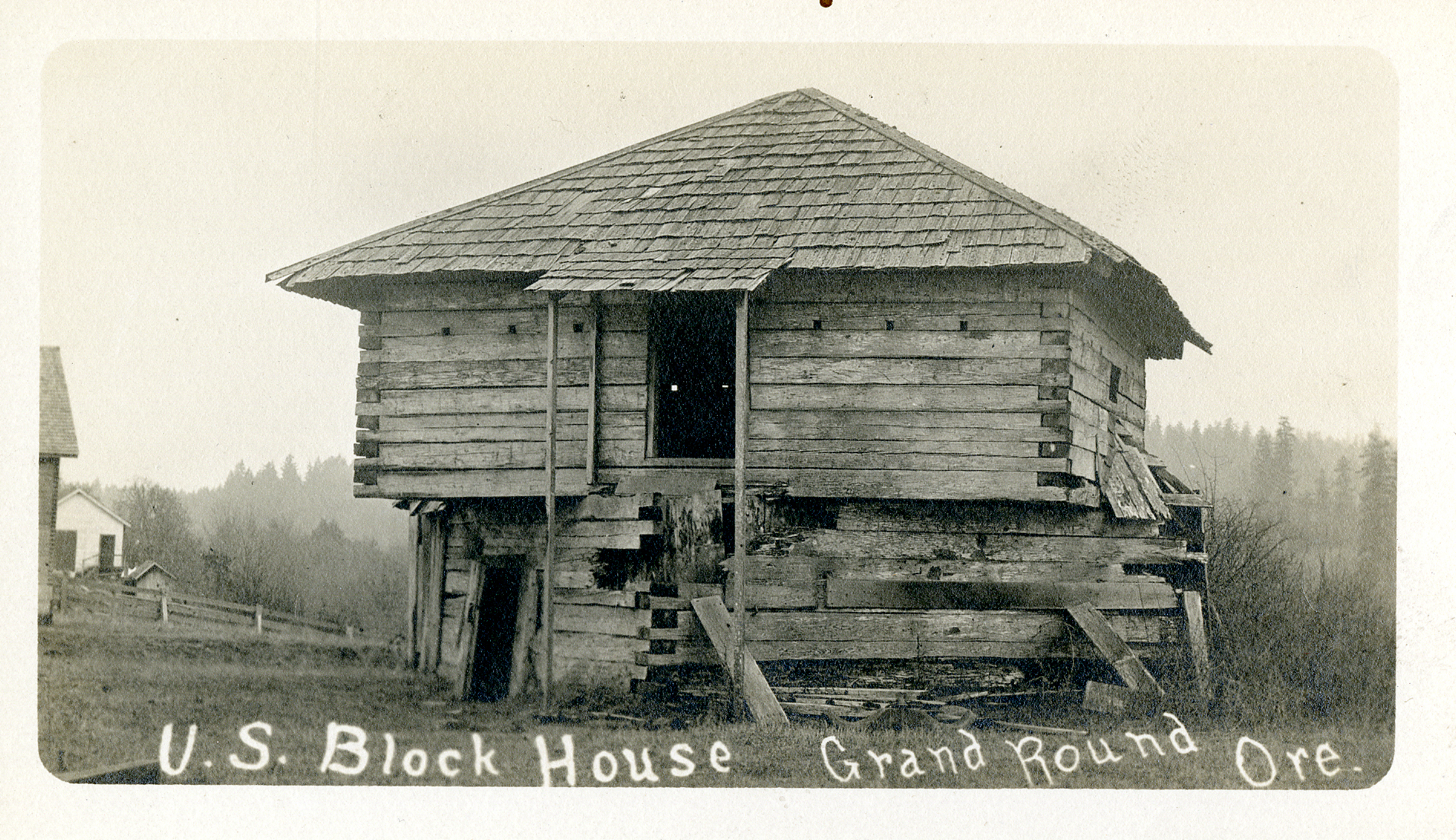

At the request of Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer and in accordance with treaties he negotiated, Wool aided in relocating tribes in southwest Oregon to temporary reserves and then to the Coast Reservation, where they could theoretically be protected from civilians bent on genocide. He also helped expand the Coast Reservation to include the Yamhill River Agency, later known as the Grand Ronde Agency, and directed the establishment of several forts, including Fort Cascades on the Columbia River in 1855 and Fort Hoskins, Fort Umpqua, and Fort Yamhill in 1856.

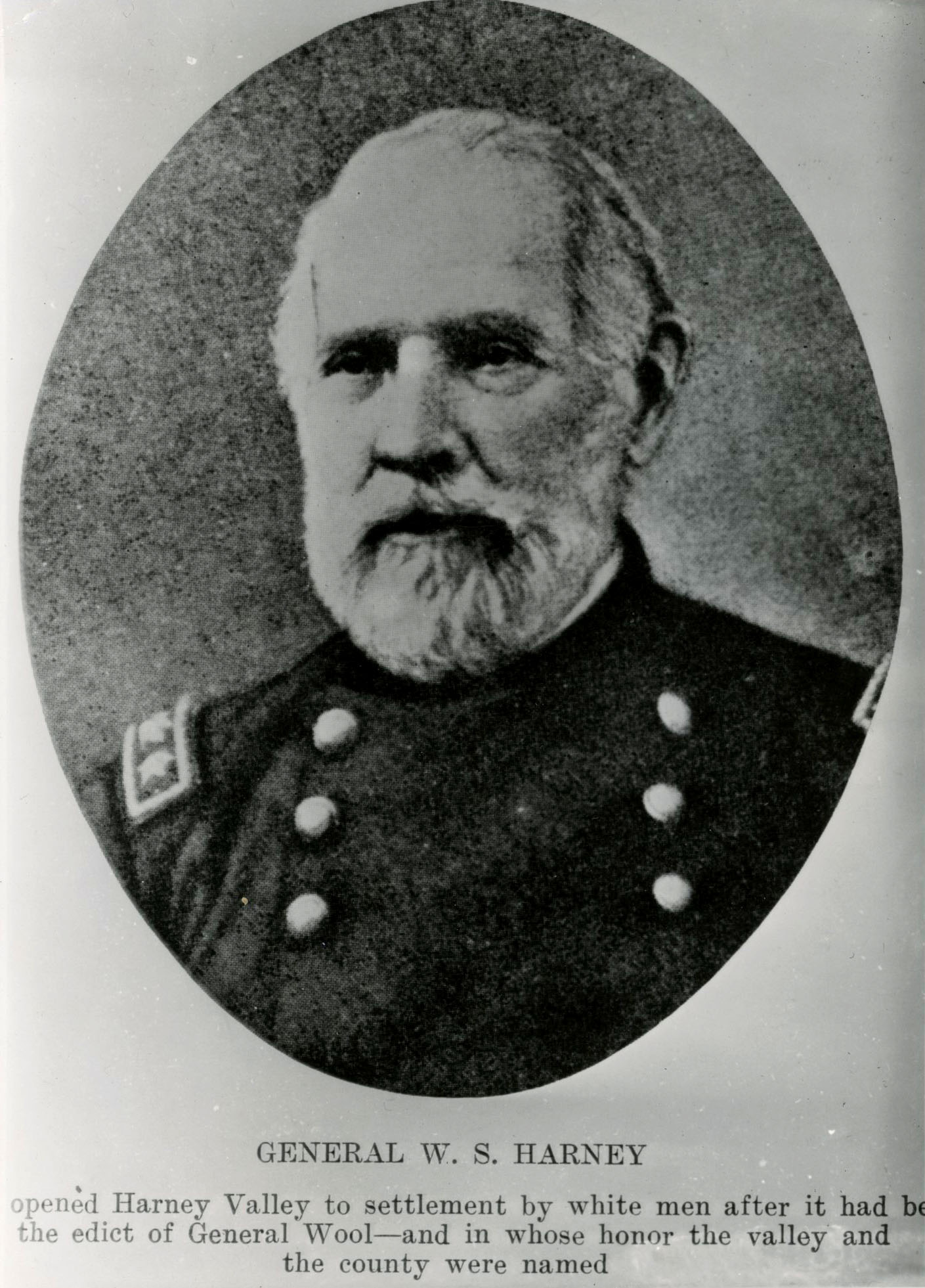

Disapproval of Wool intensified as the last Rogue River War approached its end in 1856. Combined with the ongoing public conflict with Stevens and Curry and political missteps in California, the derision proved too much for Wool to weather politically. He was reassigned to an eastern command in 1857, and the army’s structure in the West was subsequently reorganized, bringing a department-level command to Oregon and a brash new general in William S. Harney.

Wool continued his military service into the early years of the Civil War, retiring in 1863. He died at his home in Troy, New York, in 1869.

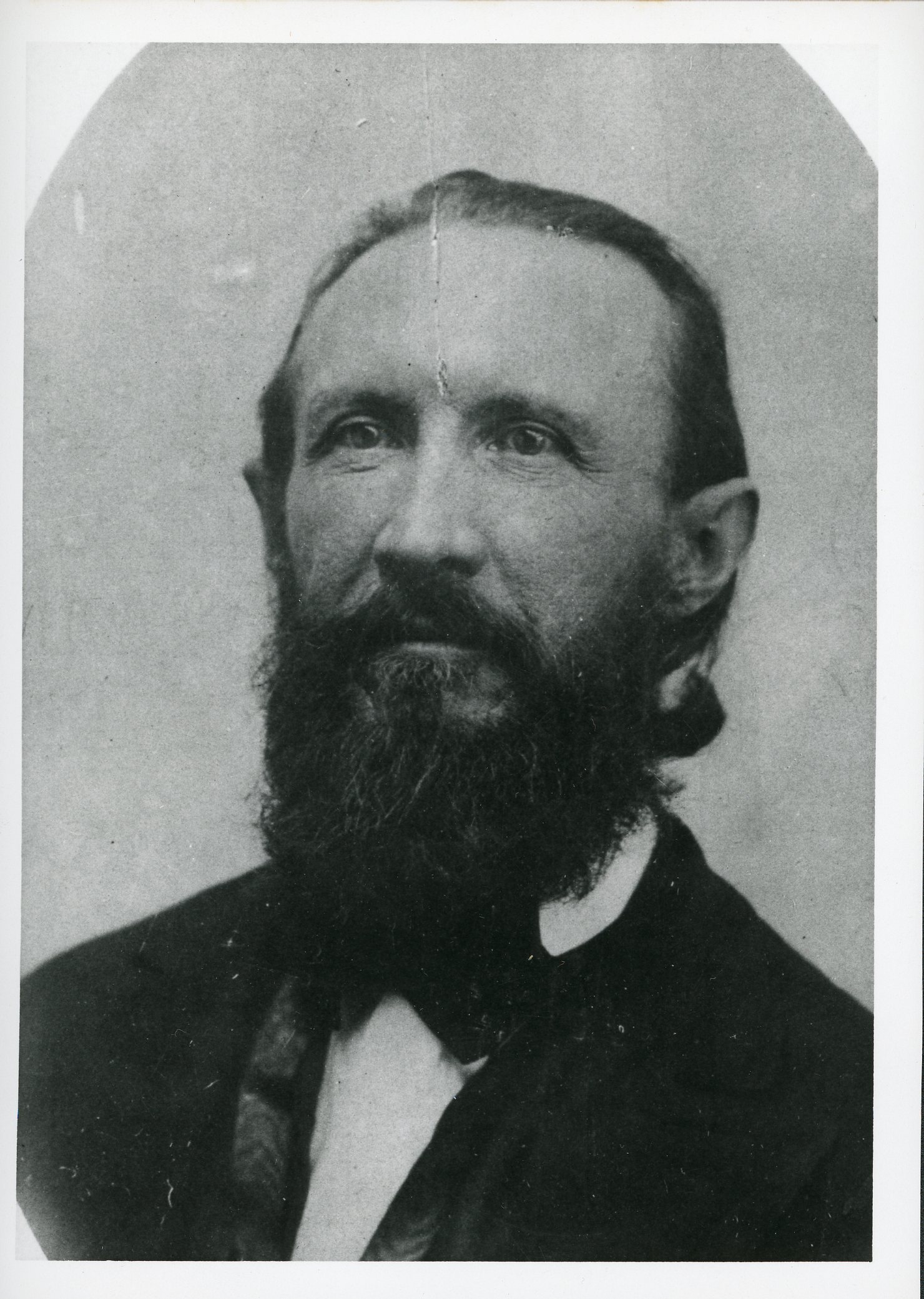

-

![]()

General John Wool.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi80188, photo file 1134

-

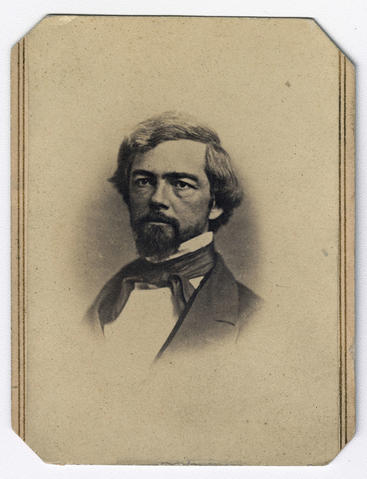

![]()

John E. Wool, full-length portrait.

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Related Entries

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)]()

Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)

Fort Umpqua was a small but important post in the Hudson’s Bay Company’…

-

![Fort Yamhill Blockhouse]()

Fort Yamhill Blockhouse

The Fort Yamhill Blockhouse is one of the few architectural remnants fr…

-

![George Law Curry (1820-1878)]()

George Law Curry (1820-1878)

A significant figure in the years before Oregon became a state, George …

-

![Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)]()

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (1818-1862)

Isaac Stevens strode through the Northwest's formative years (1853-1861…

-

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

-

![William Selby Harney (1800-1889)]()

William Selby Harney (1800-1889)

A brash, opportunistic cavalry officer with an explosive temper and a v…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ball, Durwood. Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Lewis, David G., and Robert Kentta. “Western Oregon Reservations: Two Perspectives on Place.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 111, no. 4 (Winter 2010).Terence

O’Donnell, Terence. An Arrow in the Earth: General Joel Palmer and the Indians of Oregon. Portland, Ore.: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1991.

U.S. Senate. Message of the President of the United States, Communicating . . . the Instructions and Correspondence Between the Government and Major General Wool. 33rd Cong., 2nd Sess., 1855, Ex. Doc. 16, Serial 751.

Utley, Robert M. Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848-1865. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1967.

Whaley, Gray H. Oregon and the Collapse of Illahee. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

“Gen. Wool to Col. Nesmith.” The Oregon Argus, December 8, 1855, 1.

“Gen. Wool – Gov. Curry – The Oregon and California Press.” The Oregon Argus, February 9, 1856, 2.