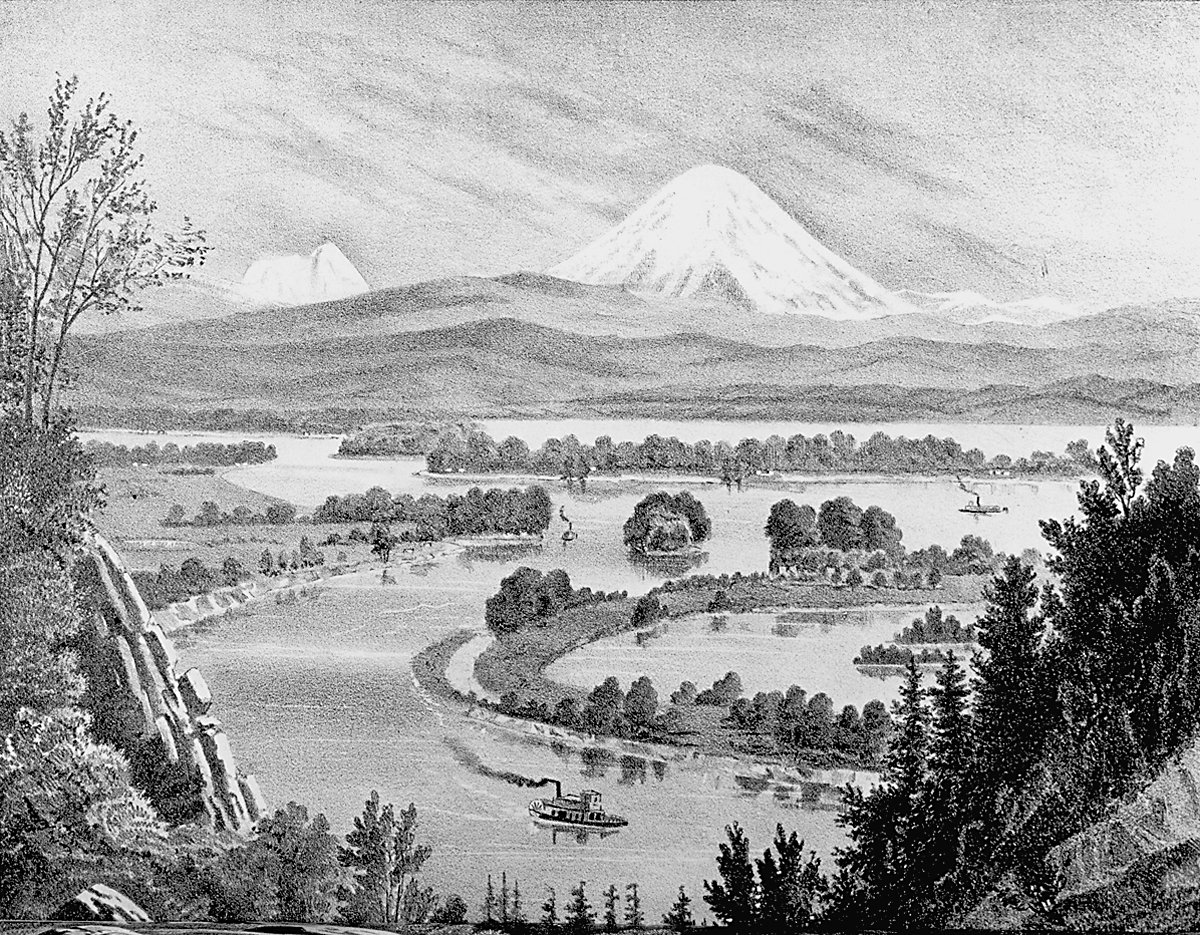

The Albany area—situated at the confluence of the Calapooia and Willamette rivers and surrounded by one of the broadest and most level stretches of the Willamette Valley—embodied the promise of the Oregon Country in the mid-nineteenth century. Named the Linn County seat in 1851, and linked to markets by regular steamboat service, Albany prospered as a political and commercial center, typifying much of the early development in the mid-Willamette Valley.

The lower Calapooia River was an important wintering area for Native peoples, accommodating a number of regular village sites; the mouth of the river served as a summer village site for remnants of different Kalapuya Indian bands in the early 1850s.

Devastating small pox and malaria epidemics had decimated the Native population of the area by 1845 when Hiram Smead filed the first land claim at the site of Albany. Smead was soon followed by other migrants, including Thomas and Walter Monteith, who acquired Smead’s claim in 1848 and laid out the town of Albany—named after the capital of their home state of New York.

Between 1849 and 1855, the nearby rival town of Takenah vied with Albany for dominance, until the two were combined in 1855 by an act of the Territorial Legislature. The contest between Takenah and Albany represented a larger divide between a working-class, Democratic segment with pro-Confederacy sympathies (Takenah), and a merchant-class, Republican, pro-Union element associated with the Monteiths (Albany). Soon commercial development transformed Albany into a prosperous shipping, processing, and production center for the region's growing agricultural economy. By the mid-1860s, five Albany-based riverboats plied the Willamette from Corvallis to Portland, making the city’s downtown business area an important regional commercial district.

The arrival of the Oregon and California Railroad in 1871 greatly furthered Albany's growth, as did the 1880 completion of a canal bringing drinking water and hydropower from the Cascade foothills to the growing city. The railroad and the canal project also brought seventy to eighty Chinese-born residents, who occupied a one-block section of downtown. The city’s largely white workforce was employed by a number of small factories and food processing centers.

With the Great Depression and World War II, significant changes altered the town's course. One of these was the closing of Albany College, first established in 1867, and its relocation to Portland in 1938, where it was opened as Lewis and Clark College in 1941. Another economic change occurred during the timber-harvesting boom of the 1930s and 1940s, when the city became a major lumber processing center. In 1940, Albany hosted the first World Championship Timber Carnival, an annual event that drew crowds for five decades before being discontinued.

World War II brought new growth to Albany when military contracts for lumber products added jobs in the region’s timber industry, a trend that would continue during the post-war housing boom. The city also provided off-base housing for nearby Camp Adair (an Army training and cantonment camp from 1942 to 1946), and became a center for shopping and entertainment for the personnel at the camp.

In 1942, the U.S. Bureau of Mines established a research center on the old Albany College campus, focusing on the development of new metallurgical processes. First known as the Northwest Electro-development Facility, the site produced titanium and zirconium and fostered the growth of a new rare metals industry in Albany led by internationally recognized companies like the Oregon Metallurgical Company (Oremet) and Wah Chang.

In the late twentieth century, the rare metals industry had become part of a diversified manufacturing base that included old mainstays like lumber and agricultural processing, as well as government services, healthcare, shipping, and distribution. The establishment of Linn-Benton Community College in 1966, and the growth of Linn County's grass seed industry ("Grass Seed Capital of the World") added to this general trend of diversification. Nevertheless, the rapid decline of the timber industry in the 1980s and 1990s hit Albany hard. The annexation of North Albany—across the Willamette River in Benton County—in 1991 allowed the city to expand during the economic contraction and brought higher-end real estate into the city limits. In the next two decades, North Albany saw significant population and economic growth.

As it was in its beginning years, Albany is still a vital commercial, social, and economic hub of the Willamette Valley. The city also carefully guards its physical history. Two residential neighborhoods and the downtown commercial district were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in the early 1980s. Together they preserve the greatest variety of historic housing styles in Oregon and remain the cornerstones of the city's identity.

-

![]()

First Street, Albany, Oregon, c. 1910.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba007996

-

Albany, Oregon.

River traffic at Albany

Related Entries

-

![Adair Village]()

Adair Village

The city of Adair Village is located in Benton County about seven miles…

-

![Albany Arts Festival]()

Albany Arts Festival

The Albany Spring Arts Festival was a highlight of Albany from 1970 unt…

-

Albany Democrat-Herald

Newspapers on the western frontier were partisan and frequently flaunte…

-

![Albany streetcar system]()

Albany streetcar system

The Albany Street Railway Company began operation on August 30, 1889, w…

-

![Albany Timber Carnival]()

Albany Timber Carnival

From 1941 through 2000, the Albany Timber Carnival was held almost ever…

-

![Allann Bros Coffee]()

Allann Bros Coffee

In the new American coffee culture, Albany-based Allann Bros Coffee car…

-

![Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s]()

Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s

In 1972, historian Alfred Crosby introduced the term Columbian Exchange…

-

![Grass seed industry]()

Grass seed industry

The Willamette Valley, with its temperate climate, wet winters, and ari…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Mae Yih (1928–)]()

Mae Yih (1928–)

Upon her election to the Oregon House of Representatives in 1976, Mae Y…

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boag, Peter G. Environment and Experience: Settlement Culture in Nineteenth-Century Oregon. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

Boyd, Robert. The Coming of the Spirit of Pestilence: Introduced Infectious Diseases and Population Decline Among Northwest Coast Indians, 1774-1874. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Potts, Robert. Remembering When: A Photo Collection of Historic Albany, Oregon, vols. I-V. Albany: Linn County Historical Society, 1991.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Conflict: the Oregon Story, 1940-2000. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.