High-quality water and ideal conditions for growing hops set the stage for Oregon’s vibrant beer industry. The earliest commercial breweries in the 1850s were small, but within a few years German immigrant Henry Weinhard had bought the first liquor license in Portland and opened Weinhard City Brewery, which would brew beer for over 130 years. By 2020, Oregon was fourth in the nation in the number of breweries and tenth in the number of craft breweries.

The story of brewing in Oregon is intertwined with the history of immigration, transportation, agriculture, Prohibition, and urbanization. Liquor was popular in the West as early as the 1830s, when fur traders distilled a beverage known as “Blue Ruin,” which they traded with local Natives. Men stationed at Fort Vancouver imported beer, and missionary Hiram Bingham wrote in 1829 that they cultivated and malted barley for beer and anticipated “exporting in small quantity.” Hard liquor was popular with early white settlers, and some engaged in small-scale brewing, but it wasn’t until the 1850s that commercial beer production began in earnest in Oregon.

An 1854 issue of the Weekly Oregonian carried the first advertisement for a commercial brewery in the Oregon Territory, appearing alongside ads for whiskey, bakeries, wagon shops, and hotels. By 1859, breweries were operating in The Dalles, Jacksonville, Oregon City, and Portland. As the population grew, small breweries opened throughout the state, saloons and mercantile shops that sold alcohol were often among the earliest businesses, and even remote towns had a ready customer base in the men who worked in the mining, logging, fishing, and canning industries.

The breweries were short-lived, however, changing names frequently and leaving behind no business records. While it is difficult to accurately calculate the dates of operation or the number of breweries in Oregon during the years before Prohibition in 1920, an examination of licenses and advertisements indicates that between 1854 and 1914, the year Oregon prohibited the sale of alcohol, a hundred breweries were licensed in the state. Some of the brewers were from England, France, and Switzerland, but most were Germans who brewed and sold variations of traditional German lager or steam beer, which uses a lager yeast but is fermented at ale temperatures (62-75° F) to compensate for the lack of refrigeration. Early brewers also produced porters, including Flat, Philadelphia XXX Ale, XX Cream, and Boag’s XXX Ale.

A New Brewing Industry

The first verifiable record of a brewery in Oregon is an advertisement for the Portland Brewery and General Grocery Establishment in the August 5, 1854, Weekly Oregonian. English-born Charles Barrett, later a well-known bookstore owner, operated the business on Front Street and sold merchandise—such as sperm candles, salt ham, matches, and stone jugs—and alcoholic spirits, wine, and beer in casks and bottles. He operated the brewery from 1852 to 1855.

Many sources name Henry Saxer, who immigrated to the United States from Switzerland in 1850, as Oregon’s first commercial brewer. There is ambiguity surrounding the date he opened Liberty Brewing in Portland, and many sources have repeated the unverifiable date of 1852. Harvey Scott’s History of Portland, Oregon mentions Saxer’s as the first brewery but without a date of establishment. When Saxer died forty-three years later, the Oregonian wrote in his December 11, 1895, obituary that “Mr. Saxer came…to Oregon in 1852. He was engaged in the brewing business, and, on reaching Portland, he established what was then known as the Liberty brewing,” leaving it unclear whether Saxer opened a brewery in the city in 1852 or at some later date. The first published advertisement for Liberty Brewing was in the July 26, 1856, Weekly Oregonian, which listed Saxer and Louis (Lewis) Behrens as proprietors of a lager beer brewery at present-day Naito Parkway and Davis Street, on property they had bought that year from George Flanders. A June 20, 1857, Weekly Oregonian advertisement listed Saxer as a sole proprietor. Saxer sold the Liberty Brewing to Henry Weinhard in 1862, and by 1866 was the owner of the California Wine Depot. In his obituary, he is credited with bringing California wines to Portland. Behrens reportedly operated a brewery in Oregon City in 1858–1862 and opened a brewery in Eugene in 1867.

Henry Weinhard’s City Brewery was in a class of its own in terms of size, distribution, and reputation. Weinhard immigrated to American in 1852 and settled in the Pacific Northwest in 1856. He worked with John Muench (also spelled "Meany," "Maney," "Menig," and "Minnich") at his Vancouver Brewery for six months, selling beer to soldiers from Fort Vancouver before opening the Bottler Brewery in Portland with George Bottler. He returned to Vancouver to work with Muench and purchased the brewery from him in 1859. In 1862, Weinhard secured the first liquor license in Portland, bought Saxer’s brewery, and opened City Brewery with Bottler, which they converted into a saloon. He bought out Bottler’s interest in 1865 and until about 1871 partnered with William Dellinger to run the West Burnside Street facility. When Weinhard died in 1904, Paul Wessinger, his son-in-law, inherited the business, which in 1905 produced 35,000 barrels, more than any other brewery in the state. The company merged with the Portland Brewing Company in 1928, becoming the Blitz–Weinhard Company, and the Wessinger family was involved until the Miller Brewing Company bought the business and closed the Burnside brewery in 1999.

A Diverse Business

Most breweries had basic brewing equipment—kettles, a furnace, a mash tun, a kiln—and storage for grain. Those who bottled their beer either did so off-site or added a bottling works as part of an expansion. Where there was variety was in production. For example, Anton Ahrens, who later co-owned a brewery in McMinnville with W. R. Bachman, produced just 40 barrels at his St. Paul brewery in 1875. Charles Kiefer’s brewery in Albany (1866–1891) produced 500 barrels in 1885, a more typical annual production. Breweries with higher production included Louis Feurer’s Gambrinus Brewing Company in Portland (1875–1916), which produced 8,000 barrels in 1889 and 14,000 in 1915, and Henry Rust’s Pacific Brewery in Baker City (1874–1916), which filled 12,000 barrels in 1903.

Some brewers, such as John Kopp in Astoria, expanded his facilities to meet increased demand. The owner of Bayview Brewery in Seattle, Kopp moved to Astoria in 1884 and opened North Pacific Brewery, at one point producing 15,000 barrels a year and employing ten to fifteen people. He built a second facility in 1896, and some said the mortar for the building was mixed with beer instead of water. In 1905, he opened a branch brewery at Eighteenth Avenue and Upshur Street in Portland and established a sales and distribution office. Kopp made a variety of styles, including an Extra Fine Bohemian Lager Beer and XX Porter, and the Daily Morning Astorian reported on July 25, 1889, that his Extra Fine Steam Beer was “as good a steam beer as is made on the Pacific Coast.” As the calls for a ban on alcohol became louder in 1908, he marketed a nonalcoholic beer called Maltona.

Oregon’s hops industry was also growing during these decades. In 1867, William Wells and Adam Weisner had planted the first hop yard in Oregon at Buena Vista in the mid-Willamette Valley, and by 1895 the state was producing more hops than any state except New York. Oregon retained that position until 1915, when California took the lead for several years. Planting decreased overall during the first years of Oregon's Prohibition period (1914-1916), but after World War I Oregon’s hop production made steady gains due to the increased acreage given to the crop and the general effect of the war on agriculture in Europe. From 1922 to 1943, Oregon was the nation's largest producer of hops; and by the 1930s, following the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment in 1933, the area around Independence was called the Hop Center of the World.

Oregon brewers benefited from a well-established transportation network in the Willamette Valley, which gave them access to the Willamette and Columbia Rivers and allowed them to efficiently import ingredients and ship their products. In 1859, the Oregon Argus in Oregon City reported that a new brewery in the “flourishing city” of The Dalles on the Columbia was producing ale, porter, and lager beer and sometimes whiskey. A few years later, in 1863, newspapers advertised Ludwig’s Columbia Brewery (1859–1916) as the largest and most complete brewing establishment in the state and noted that the railroad passed “immediately in front of the Brewery,” which included a “handsomely fitted up saloon” and a “neatly furnished room for the accommodation of private parties.”

Other brewers found opportunities in other parts of the state. John Gottlieb Mehl, for example, opened the Roseburg Brewery in 1861, the first in that town. In 1866, he partnered with Swiss-born John Rast, who bought Mehl’s shares in 1871 after the brewery burned down. Mehl moved his family to Oakland, Oregon, then Coquille City, and then Bandon, opening breweries in each town. He died in 1893 while constructing the Bandon Brewery, and his wife Mary ran the Bandon business until 1896, when she sold it to Joseph Walser.

Regardless of location, there was no shortage of saloons in Oregon, and it was common practice for brewers to offer discounts or gratuities to saloonkeepers as incentives to sell their products. But unpaid bills kept profits low for smaller brewers. “To counteract such issues,” Lyndsay Danielle Smith wrote in 2018, “brewers began investing in saloons by financing fixtures such as bars, mirrors, or sideboards to saloonkeepers. Commonly, brewers added a clause in the fixture mortgages limiting the brands of beer that saloonkeepers could sell.”

Marriage, debt, and death played their parts in family business management. J. J. Holman opened the Eagle Brewery in Jacksonville in 1856 and sold the business in 1859 to Joseph Wetterer, a German brewer, who added a saloon and family residence. Wetterer’s production increased, and within a couple of years the brewery was known for its lager, distilled whiskey, and brandy. Although the business was successful, when Wetterer died in 1879 he left significant debts for his wife Frederica. The brewery closed in 1880, but her father, Joseph Sage, paid off the mortgage and transferred the property to her the next year. In 1883, she married William Heeley, a former employee, and the brewery was renamed the William and Frederica Heeley Brewery.

William Neurath opened the Grants Pass Brewery in 1887, which he soon sold to Eugene and Marie Kienlen. After an 1899 fire, the couple rebuilt and added a saloon. It’s unclear who managed the brewing operations, but Marie purportedly had a brewing degree from the New York Brewers’ Association. At the time of Eugene’s death in March 1904, the properties and business were transferred to Marie, although in August 1904 she had to pay $7,000 to Philomena Kienlen, Eugene’s legal wife in Minnesota. Four years later, Marie married Eugene’s nephew, Sam Kienlen, but the brewery closed in 1912 after Sam was repeatedly fined for selling beer on Sunday.

Prohibition

Efforts to ban alcohol in Oregon pre-dated statehood (1859); but when the Oregon Woman's Christian Temperance Union held its first meeting in 1883 at a Methodist church a few blocks from Weinhard's brewery in Portland, the "Bonnet Brigade" became an unstoppable political force. It wasn’t until voters approved the local option act in 1904, which allowed cities and counties to hold elections to ban alcohol for their residents, that Oregon took a major step toward legal Prohibition. Several cities and counties voted “dry” in the following years, and on November 3, 1914, Oregonians voted for a statewide ban on alcohol (to be enacted in 1916).

The owners of large facilities and established breweries repurposed their operations. Stockholders in Roseburg considered building a cannery to replace the Roseburg Brewing and Ice Company, and brewers in La Grande and Klamath Falls investigated converting their facilities to denatured alcohol plants. Local newspapers shared stories of sauerkraut made in kegs, candy stores replacing saloons, clothing dye made from yeast, and growing mushrooms in breweries rather than making beer.

Other breweries used their equipment in more predictable ways. The Henry Weinhard Brewery “unbranded” itself and sold vinegar, ice, soda supplies, and soft drinks under the label Weinhard's Puritan Brand Sodas. The Salem Brewery Association, opened by Samuel Adolph as the Pacific Brewery in 1866, was owned by Leopold Schmidt after 1903. Schmidt owned breweries in Olympia, Salem, and Bellingham, and during Prohibition he partnered with Northwest Fruit Products in Salem to bottle Loju, a loganberry juice. Renamed the Phez Company in 1919, it also sold other unfermented fruit juices. The brewery reopened in 1933 but was sold the following year to Emil G. Sick, who owned Sicks’ Seattle Brewing Company.

Prohibition was repealed in Oregon by initiative in 1932 and ended on the federal level in 1933. The local option was still legal, however, and a few counties and towns carried their dry status into the twenty-first century.

Craft Comes to Oregon

The only breweries in Oregon after Prohibition were the Blitz-Weinhard Company, Sicks’ Brewing Company in Salem, and Julius Roesch’s City Brewery in Pendleton (Roesch’s La Grande brewery closed in 1916). Breweries began to consolidate, and by 1980, the top ten breweries in the nation were making 93 percent of the beer. Lucky Lager, brewed in California, and Olympia and Rainier, both brewed in Washington, were the nearest that Oregon drinkers could get to local beer.

The 1970s and 1980s were decades of growth in the industry. In the early 1970s, brewer and writer Fred Eckhardt became a proponent of microbrews and urged his readers to focus on flavors and styles rather than intoxication. Writing for the Oregonian and national publications such as Celebrator Beer News and All About Beer, his promotion of small breweries was important for the growth of the Northwest beer industry. In Portland, brothers Mike and Brian McMenamin opened Produce Row Café in 1974, and Don Younger opened Horse Brass Pub in 1976. The McMenamins opened Oregon’s first brewpub in Hillsdale, a southwest Portland neighborhood, in 1985; they opened the Mission Theater & Pub in 1987, the first theater pub in the state.

Until the spring of 1980, when Charles “Chuck” and Shirley Coury opened Cartwright Brewing Company in Portland, all microbrews in Oregon were imported. Trained as a vintner, Chuck Coury had found recipes in “beautiful, old brewing textbooks” in the Multnomah County Library, and their first offering, Cartwright Portland, was a mild English-style ale, which they followed with Legal Lager and Deliverance Ale. The beer sold for nearly a dollar a bottle, more than customers expected to pay, but inconsistency was a larger issue than price. Cartwright Brewing closed in 1981, but the company had roused consumers’ appetites for locally made beer and inspired those who opened small breweries a few years later.

The year 1984 was pivotal for three Portland breweries: BridgePort, Widmer Brewing, and Portland Brewing. Winemakers Richard and Nancy Ponzi opened Columbia River Brewing (later named BridgePort) in 1984 and hired Karl Ockert as brewmaster. BridgePort Ale was their first success, followed by BridgePort India Pale Ale, Blue Heron Pale Ale, and barley wine Old Knucklehead. BridgePort was acquired by the Gambrinus Company in 1995, and the brewery closed in 2019.

Brothers Kurt and Rob Widmer also opened a brewery that year. Their first beer was a Dusseldorf-style Alt, and in 1986 they introduced their flagship Hefeweizen. Anheuser-Busch purchased a minority stake in the company in 1997, and Redhook Ale and Widmer Brothers merged in 2007 to form the Craft Brewers Alliance (later Craft Brew Alliance).

Fred Bowman and Art Larrance registered the name Portland Brewing Company in 1984, secured a franchise agreement to make Bert Grant’s Scottish Ale and Russian Imperial Stout, and opened for business in 1986. In 1992, the company named its flagship product MacTarnahan’s Amber Ale, in honor of one of their investors, Robert Malcolm "Mac" MacTarnahan. The company is now owned by the Florida Ice & Farm Company.

On July 13, 1985, Governor Vic Atiyeh signed Senate Bill 813, the “Brewpub Bill,” which gave brewers permission to make and sell beer on the same premises, allowing them to gain new customers and increase their revenue. Four new breweries soon opened in Oregon: Full Sail Brewing (Hood River) and Oregon Trail Brewery (Corvallis) in 1987 and Deschutes Brewery (Bend) and Rogue Ales (originally in Ashland) in 1988. Portland had the largest concentration of breweries, and the industry in central Oregon saw considerable growth, but breweries also opened in Albany (Calapooia, 1993), Redmond (Cascade Lakes Brewing Company, 1994), Enterprise (Terminal Gravity, 1960), Baker City (Barley Brown’s, 1998), Medford (Walkabout Brewing, 1997), Eugene (Ninkasi, 2006), Astoria (Fort George, 2007), and Corvallis (Block 15, 2008).

Education and Events

Since 1995, the Fermentation Science program in the Food Science and Technology Department at Oregon State University has been a leader in brewer education. Founded in Portland in 1979, the Oregon Brew Crew is one of the oldest and largest home brewing clubs in the United States, meeting at F. H. Steinbart, a homebrew shop founded in 1918, the oldest in the nation. Other pioneering clubs include the Heart of the Valley Homebrewers (1982, Corvallis) and the Cascade Brewers Society (1982, Eugene).

The nonprofit Oregon Brewers Guild, one of the nation's oldest craft brewer associations, was founded in 1992 to advocate for the state’s breweries. And the Pink Boots Society was founded in 2007 by Teri Fahrendorf, former brewmaster at Steelhead Brewing in Eugene, as a professional organization to support women in the brewing industry. Pink Boots members created Barley’s Angels in 2011 as an educational community for consumers; it became its own organization in 2012.

The Oregon Homebrew Festival in Corvallis, established in 1982, is the Pacific Northwest’s oldest homebrew competition; others include the KLCC Brewfest Homebrew Competition and SheBrew. The Oregon Brewers Festival, established 1988, is one of the nation’s longest running and largest craft beer festivals in the nation. Oregon also hosts the Portland Craft Beer Festival, the Festival of Dark Arts in Astoria, the Bend Brewfest, and Mt. Angel's Oktoberfest.

According to the Brewers Association, 311 craft breweries were operating in the state in 2019, making Oregon tenth in the nation, with 9.7 breweries per 100,000 adults over twenty-one years old. Although about forty breweries closed between 2014 and 2019, over the same period the state added approximately 130 new breweries. The beer industry in 2016 contributed $6.6 billion to the economy and supported over 40,000 jobs.

Much has changed since Charles Barrett’s 1854 advertisement in the Oregonian.

-

![]()

Civil War soldiers drinking beer in a Jacksonville tavern, likely the Eagle, in 1863..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Orhi21090

-

![]()

A glass carboy, used to ferment beer and wine, brought to Oregon on the Oregon Trail, c.1850..

Courtesy Oregon Historical Society Museum

-

![]()

Pacific Brewery, Baker, 1889.

Courtesy Baker County Library, e10398b

-

![]()

Columbia Saloon, Weinhard's Brewery, Portland.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 11984, photo file 1745

-

![]()

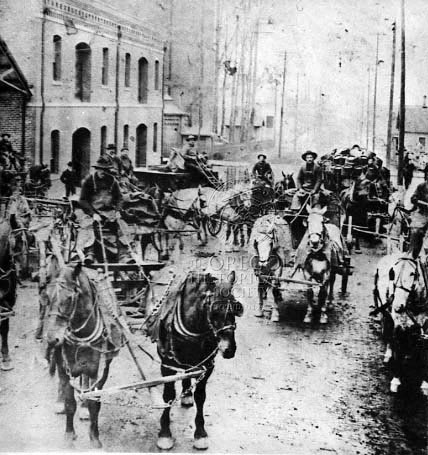

City Brewery and its delivery wagons, Portland, 1890.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Society Research Lib., Orhi11983

-

![]()

The U.S. Brewery on Harrison, Portland, 1896.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 019182

-

![]()

Salem Brewery Association, bottle house.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Cronise, 0166G022

-

![]()

William Killduff and an unknown associate drink beer in the Weinhard delivery truck, Portland, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Orhi048942

-

![]()

A display of Acme Beer, c.1930s.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 372A1180

-

![]()

Columbia Beverage Company, SE 13th and Division, Portland, 1936.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 372A1177

-

![]()

The Oregon State University Pilot Plant Brewhouse on campus.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries

-

![]()

Delegates of the Northwestern Brewmasters Convention in Seattle, 1937.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Society Research Lib., 022262

-

![]()

Blitz-Weinhard warehouse, 12th and Couch, Portland, 1950.

Courtesy Oregon HIst. Society Research Lib., 007317

-

![]()

An automatic bottle filler, handling 135 bottles at a time, at the Blitz-Weinhard Brewery, Portland, 1956.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 006615

Related Entries

-

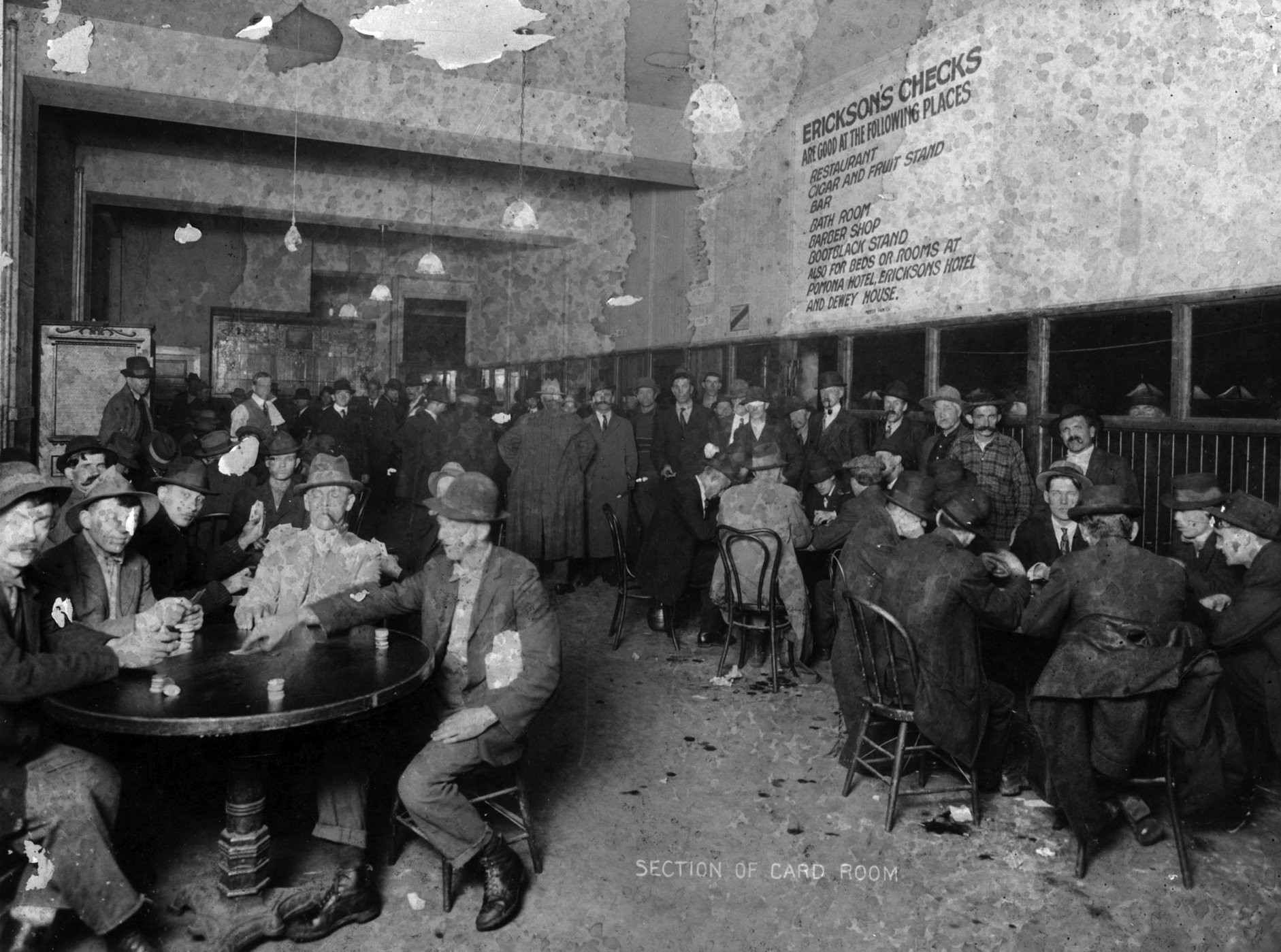

![Erickson's Saloon]()

Erickson's Saloon

Erickson’s Saloon, sometimes called the Working Man’s Club or The Erick…

-

![Full Sail Brewing Company]()

Full Sail Brewing Company

Founded in 1987 in Hood River, the Full Sail Brewing Company is one of …

-

![Hop Industry]()

Hop Industry

Hops are perennial, cone-producing, climbing plants native to Europe, A…

-

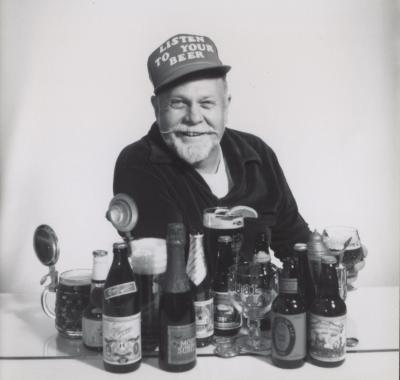

![Otto Frederick "Fred" Eckhardt (1926–2015)]()

Otto Frederick "Fred" Eckhardt (1926–2015)

Friends and fans called Fred Eckhardt a muse, an icon, a founding fathe…

-

![Rast Brewery]()

Rast Brewery

The inaugural issue of the Roseburg Ensign, on April 30, 1867, advertis…

-

![Salem Brewery Association]()

Salem Brewery Association

The Salem Brewery Association, incorporated in 1903, was at one time th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abernathy, Jon. Bend Beer: A history of brewing in Central Oregon. Charleston, SC: American Palate, a Division of The History Press, 2014.

Alworth, Jeff. The Widmer Way: How Two Brothers Led Portland's Craft Beer Revolution. Portland, Ore.: Ooligan Press, 2019.

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. History of Oregon; Vol. 2: 1848-1888. San Francisco, Calif: History Co., 1888.

Blue, George. "Green's Missionary Report on Oregon." Oregon Historical Quarterly 30.3 (1929).

Bull, Donald, and Manfred Friedrich. The Register of United States Breweries, 1876-1976. Trumbull, Conn: Bull, 1976.

Busse, Phil. Southern Oregon Beer: A Pioneering History. Charleston, SC: American Palate, a Division of The History Press, 2019.

Dunlop, Pete. Portland Beer: Crafting the Road to Beervana. Charleston, SC: American Palate, a Division of The History Press, 2013.

Elkins, Al. “Henry Weinhard.” Brewery Collectables Club of America, 2016. https://www.bcca.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Henry-Weinhard.pdf

Hankel, Evelyn G. “Early Astoria Breweries" Clatsop County Historical Society Cumtux 9.3 (1989).

Ingraham, Aukjen T. “Henry Weinhard and Portland's City Brewery.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 102.2 (2001).

Kopp, Peter A. Hoptopia: A World of Agriculture and Beer in Oregon's Willamette Valley. University of California Press, 2016.

Meier, Gloria and Gary. Brewed in the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Ford Press, 1991.

Portrait and Biographical Record of Portland and Vicinity, Oregon: Containing Original Sketches of Many Well-Known Citizens of the past and Present. Chicago: Chapman Pub., 1903.

Smith, Lyndsay Danielle. “A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920,” MA Thesis, Portland State University, 2018.

Stursa, Scott, and Margarett Waterbury, Distilled in Oregon: A History & Guide with Cocktail Recipes. Charleston, SC: American Palate, 2017.

Sulerud, George L. Station Bulletin 288: An Economic Study of the Hop Industry in Oregon. Agricultural Experiment Station, Oregon State Agricultural College, Corvallis, Or, 1931 http://bit.ly/2Ijsmkp

Van, Wieren D. P., and Donald Bull. American Breweries II. West Point, PA: Eastern Coast Brew[er]iana Association, 1995