The arrival of Latinos in Oregon began with Spanish explorations in the sixteenth century. In 1542-1543, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, sailing from the port of Navidad in Mexico, reached what is today the California-Oregon state line. Explorations by Spaniards continued with Sebastián Vizcaíno’s arrival on the Oregon Coast in 1602-1603. One of Vizcaíno's commanders, Martín de Aguilar, kept a log that contains one of the first written descriptions of the Oregon Coast. Vizcaíno set out from Mexico in 1602 in search of usable harbors and the mythical city of Quivira. While exploring along the northern California coast, a storm separated Vizcaíno and Aguilar's ships. Aguilar continued up the coast and is thought to have sighted and named Cape Blanco. He may have sailed as far north as Coos Bay. In 1774, Juan Perez reached the Oregon Coast to become the first European to describe Yaquina Head and make landfall in the present-day Oregon.

The late eighteenth-century Spanish explorations of Oregon and the Pacific Northwest were generally more concerned with territorial rights and Spain’s dominion in the region than treasure or commerce. They came to Oregon as part of a conquering and imperialistic empire. Mexican independence in the early nineteenth century brought a new phase for the Latino presence in Oregon.

Vaqueros and Mule Packers

In 1821, with Mexico’s independence from Spain, the nation gained a territory that stretched from the present-day Oregon-California state line to Central America. When the United States conquered Mexico’s northern territory in 1848—today’s California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas, Colorado, and part of Oklahoma—the U.S. acquired land but also established Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous cultures. Part of that cultural heritage included Spanish subjects and Mexicans in California who worked as vaqueros (horsemen and cattle herders) and mule packers.

Because of their skill, vaqueros were hired by American cattlemen to help with cattle drives to the Oregon Territory. Vaqueros such as Vicente and Juan Ortega, Francisco “Chico” Chararateguey, and Juan and Jesus Charris, who came to Harney County in the late nineteenth century to work on Peter French’s P Ranch, are considered among the pioneers of eastern Oregon.

Mexican mule packers and miners were descendants of generations of Spanish Mexicans who learned their trade in Mexico, the Southwest, and California, moving supplies from distribution points in northern California to areas as far north as the Illinois Valley in Oregon. Little is known about these early Mexican residents in Oregon; but according to historian Erasmo Gamboa, the U.S. Army used Mexican mule packers during conflicts with Indians in Oregon. In 1855-1856, for example, when the Rogue River War raged in southern Oregon, Mexican mule packers used pack trains to supply army troops with food and other necessities. Thirty-seven Mexicans served as support troops with the Second Regiment Oregon Mounted Volunteers. According to one scholar, “the first person of Latino origin listed in the [1850] Oregon census is Guadalupe de la Cruz, a thirteen-year old boy residing in Oregon City.” By 1860, twenty Mexicans, including five women, lived in Oregon City.

Railroad and Migrant Workers

The appearance of larger Latino communities in Oregon was the result of the development of northern Mexico and the American Southwest at the turn of the twentieth century, which pushed hundreds of thousands of Mexicans northward. Between 1910 and 1920, a million Mexicans came to the United States, causing a dramatic increase in the Mexican population along the U.S.-Mexico border. Mexicans moved to the Midwest, the Rocky Mountain region, and the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon.

It is difficult to measure with any certainty the number of Latinos in Oregon during the first two decades of the twentieth century. The 1910 Oregon Census reports that no Mexicans or Latinos lived in Oregon, but the issuance of money orders to Mexico from Oregon indicates that at least fifty Mexicans were in the state in 1900 and eighty-five in 1910. Just before World War I, the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, the Union Pacific Railroad, and the Oregon Short Line recruited Mexicans to work as laborers. In addition, the Southern Pacific Railroad had extensive lines in western Oregon and contributed to the Mexican presence by employing them, primarily to work in maintenance section gangs. The 1920, Oregon census placed the number of “foreign born” Mexicans at 569.

Recruitment efforts for Mexican labor increased as global conditions changed. The U.S. entry into World War I increased the demand for agricultural production. To circumvent not only the anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States during this period but also the restrictions of the 1917 Immigration Act, Mexicans were exempted from provisions of the act, in particular the $8 head tax and the literacy test. As a result, approximately 80,000 Mexicans worked in agriculture, railroads, mines, and canneries in the United States, many of them in Oregon. One of the early arrivals to Oregon was Santiago Jaramillo, a railroad worker in eastern Oregon. Jaramillo moved to Oregon in 1917 from Aguacalientes, Mexico, to work in Riverside, near present-day Ontario. Eventually, he owned and operated his own cattle ranch and farm in Ontario. In 1920, 37 Mexicans lived in Multnomah County.

Deportation

The Latino population in Oregon grew slowly between 1900 and 1930, when 1,568 permanent residents of Mexican ancestry lived in the state. That number did not account for the migrant labor force that was in Oregon for only part of the year—a small, but steady stream of people primarily from Texas, California, and Mexico. During the 1930s, Mexican Americans, Mexican nationals, and Latinos in general became targets and scapegoats for the economic fallout from the Great Depression. A practice of hiring only white laborers became the norm in many parts of the United States. Furthermore, local communities and eventually the U.S. government responded to the perceived problem by instituting what was called the Repatriation Program—the removal of Mexican American and Mexican nationals from the United States.

During the 1930s, 500,000 Mexicans, 250,000 of them U.S. citizens of Mexican ancestry, were either forced to leave the country or were deported to Mexico. For most of the decade, the Latinos in Oregon retreated into rural areas for fear of being deported. Instead of the roundups that occurred in Los Angeles, Detroit, and other cities, Oregon removed Mexicans through economic rationalization, nativist rhetoric, and coercion.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, a large number of Latinos in Oregon worked in agriculture. As the prices for commodities fell in the 1930s, so did wages, and many Mexicans left to find work elsewhere. Employers in Oregon began to hire “white workers only,” regardless of their legal status. New Deal legislation had little to no effect on Mexicans, because many were refused assistance, and most Mexican Americans were not told they were eligible for relief programs. For those people who were repatriated, it was a demoralizing and humiliating experience.

During the Depression, stoop labor—that is, hard labor in the fields—remained one of the few jobs many people refused to do, even as unemployment soared, primarily because that form of labor had been racialized during the 1920s. For many, stoop labor was Mexican labor. This also explains why, even as Mexicans were deported in the 1930s, a significant number remained employed in the Pacific Northwest, including in Oregon. The Depression revealed the vulnerability of Latinos in Oregon and other states, but it also reinforced the need for Latino labor.

Many Latinos came to work in the orchards and fields in Hood River and the Willamette Valley from California’s Imperial Valley. At the same time, the Oregon Short Line, the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company, and the Union Pacific Railroad hired increasing numbers of Latinos to maintain their tracks. As the 1930s came to a close, the United States became embroiled in global events that had a major impact on the Latino community in Oregon. From the Mexican American perspective, the 1930s were a time of great pressure due to the large deportation drives; but as the demands for labor increased during World War II, many of the communities and government officials that had supported deportation advocated importing Mexicans to the United States.

World War II and the Braceros

On the evening of March 13, 1945, Ignacio Garnica Espinosa, a bracero and a member of a section gang repairing a broken rail in Portland, was struck by an automobile. He died six days later. A few weeks earlier, on January 24, Enrique Davila Zapata was killed by a train in Woodburn while working for the Southern Pacific Railroad. Jose Luis Vargas Ferro was killed on December 26, 1944, when a track motorcar he was working on derailed near Chinchalo. As one of the Allies fighting fascism in World War II, Mexico made three crucial contributions to the war effort: a squadron of fighters for the war in the Philippines, oil, and 500,000 laborers for the agricultural and railroad industries in the United States. The battlefield for Mexicans was not Europe, Japan, or Africa but the U.S., where over 320 Mexicans died in 1943-1945.

Under a wartime agreement between Mexico and the United States, Oregon imported over 15,000 laborers from Mexico between 1942 and 1947. The workers in the Bracero Program, as it was called, were not the first Latinos in Oregon, but they represent a significant moment in the state’s Latino history. By the time the program ended, crops had been saved, and goods, people, and war materials had been safely transported.

Over 500,000 Latinos in the United States served in the armed forces, many with distinction, and many Latinos in Oregon volunteered and were drafted into service. Some never returned, dying in the service of the country. At the beginning of the 1940s, 1,280 Latinos lived in Oregon, and the war years brought a substantial increase in the Latino population, as Latinos migrated from other parts of the country and Mexican nationals came to Oregon and other states as part of an agreement signed by the U.S. and Mexico to provide emergency labor.

An estimated 15,000 Mexican men were recruited to work in Oregon as braceros, to alleviate the farm-labor shortage during the war and to work on railroad maintenance gangs. The braceros encountered sentiments that ranged from appreciation for their hard work to racism. In Oregon, the Bracero Program lasted until 1947, after which growers became responsible for transporting workers to and from Mexico, an expense that most of them could not afford.

At the same time, Mexican Americans also migrated to Oregon, and it was that labor force that growers preferred after the bracero program ended. It is unclear how many braceros broke their contract and remained in Oregon or returned to eventually become U.S. citizens.

Forming Communities in the 1950s

During the 1950s, Operation Wetback was a military operation that rounded up a million undocumented Mexicans for deportation. In Oregon, according to Lynn Stephen and Marcela Mendoza, “the city of Woodburn and other places where Mexican workers live were punctuated by the presence of sweeps through local farms and roads that picked up undocumented workers.” The May 15, 1953, Oregonian reported: “Agents Sweep Rising Tide of Mexican Illegals South to Border.” At the same time, many Oregon growers preferred to hire undocumented workers. As the Oregonian reported, “In addition to the Mexicans brought into this country legally, Oregon gets its share of the illegal hordes of wetbacks who sneak across the border to collect the American dollars U.S. farmers are glad to pay them.” During these uncertain times, Latinos were planting firm roots in Oregon.

Many of the Latinos who came to Oregon worked in such places as Nyssa, Hood River, Woodburn, and Independence. Julian Ruiz, a Tejano who immigrated to Oregon in the early 1950s, had a labor contracting business in Texas. In 1950, he and his father decided to move their operation to Oregon, where he worked as a laborer in the St. Paul area, lived in a labor camp, and worked harvesting hops and strawberries. He and his family also traveled to Prineville and Madras to pick and truck potatoes. They followed this routine until 1954, when they decided to settle in Woodburn. Eventually, Ruiz became a successful labor contractor who recruited hundreds of Latinos for jobs in Oregon.

In Salem, the Latino population remained small, but the diversity beyond the Mexican diaspora began to appear. Isabela Varela Ott, for example, moved to Salem in the early 1950s to live with her daughter and her husband, a native of Peru. The family was reportedly one of only four Latino families in the city in the 1950s and 1960s.

Growth, Development, and Resistance

As Oregon’s Latino population continued to grow during the 1950s and 1960s, individuals and organizations worked to improve Latinos’ lives in the state. KWRC in Woodburn, for example, began its Spanish radio programming in 1965, offering entertainment and information to the Latino community. The Oregon Council of Churches obtained an Office of Economic Opportunity grant in 1965 and formed the Valley Migrant League to provide social services for Latinos in six Oregon communities. The League played a vital leadership role by working with local, regional, and state officials on social and economic issues. Oregon Latinos were engaged in the civil rights movement at every level, and the United Farm Workers of Oregon, established in 1968, worked to improve conditions for Latino farmworkers.

Latinos also began to demand economic, political, and social equality. In 1973, Colegio Cesar Chavez was established in Mt. Angel, the only independent, accredited, degree-granting institution for Latinos in the country. In addition, Latino entrepreneurs started businesses like the Tortilleria Gonzales (1952) in Ontario and Panaderia Rodriguez (1965) in Nyssa, and political activists started groups such as Volunteers in Vanguard (VIVA) in Washington County (1966). Centro Chicano Cultural, established in 1969 between Woodburn and Gervais, was a cultural center for the Latino community in the state.

By 1970, the Latino population in Oregon had grown to 32,000. A new wave of Latino immigrants came to Oregon, most of them from Michoacan and Oaxaca, Mexico. Many of the newcomers found work on tree farms and in canneries, as well as the migrant farmworker circuit. Mexican crews also worked in the forest industry during the 1970s and 1980s, replanting logged-over areas, and in the 1990s and 2000s on contract crews fighting forest and range fires.

The Latino population in the United States began to change as civil wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala displaced a large number of people. Before 1960 and the civil war in El Salvador, there were about 10,000 people from that country in the U.S. Between 1979 and 1992, a million Salvadorans immigrated to the U.S. About 3,000 Central Americans came to Oregon in the 1970s and 1980s, adding to the diversity of the Latino community that had been primarily Mexican for most of the twentieth century.

The 1980s and 1990s

By the beginning of the 1980s, Latinos made up about 2.5 percent of the Oregon population, or 65,000 people. During that decade, immigration and immigrant labor once again became a contentious national issue, as the nation plunged into a recession. Growers had come to rely on undocumented workers, however, and the workers were responding to labor market conditions that had led many businesses to import low-cost labor to contend with economic competition from abroad. In 1986, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) and established the Special Agricultural Workers program (SAW). The act gave legal status to undocumented Latinos who had been in the country since 1982 and put in place new sanctions against employers who hired undocumented workers. In Oregon, 23,736 Mexicans and Guatemalans received permanent residency under SAW.

Between 1980 and 1990, the Latino population in Oregon grew by 70 percent. Most lived in cities, with only 33 percent living in rural areas. The creation of Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (Northwest Tree Planters and Farm Workers United, known as PCUN) in 1985 signaled the continued need to protect workers’ rights. In addition, as the Latino population increased in Oregon and elsewhere, new challenges appeared in attempts to pass English-only legislation and deny civil and political rights to undocumented immigrants. By 1990, 112,707 Latinos lived in the state.

The Twenty-First Century

Due to the recession in the early twenty-first century and the increase in deportations, the migration of Latinos declined nationally, but Oregon’s Latino population continued to grow. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of Latinos in the state increased by 63 percent, from 275,314 to 450,052—accounting for 43 percent of the population growth for Oregon during the decade. The increase was primarily due to an increase in the native-born population, which accounted for 65 percent of the growth in the Latino population after 2000.

Migration from Latin America had increased substantially during the 1990s. In Oregon, the immigrant population from Latin America nearly tripled between 1900 and 2000. While Latino immigrants in the 1970s had been largely young men working in the agricultural industry, women made up 43.8 percent of immigrants from Latin America in the twenty-first century. A significant number of immigrants worked in manufacturing, food and hospitality services, construction, and maintenance.

The highest concentration of Latinos in Oregon in the twenty-first century has been in towns with historic immigrant populations. Five cities have majority Latino populations, all of them in traditional agricultural and ranching areas: Gervais (67 percent), Boardman (62 percent), Nyssa (61 percent), Woodburn (59 percent), and Cornelius (50 percent). Larger cities in the Portland metro area, including Hillsboro, Gresham, and Beaverton, also saw significant increases in the Latino population, as did Bend in central Oregon and the eastern Oregon towns of Hermiston and Umatilla. Salem's Latino population reached 20 percent, according to the 2010 Census, and communities such as Independence in the Willamette Valley and Phoenix in the Rogue Valley also saw significant increases in their Latino populations. Oregon, like the rest of the country, experienced an increase in undocumented immigrants in the 2000s. In 2011, the Pew Hispanic Center estimated that there were 160,000 undocumented immigrants in Oregon, with approximately 60 to 75 percent of them from Mexico.

In demographic terms, Latinos in Oregon are a diverse mix of first-generation immigrants and long-term residents. In 1970, Latinos represented less than 2 percent of Oregon’s population. In 1980, the census reported that Latinos had increased to 2.5 percent, or approximately 65,000 people; in 1990, there were 4 percent, or 112,707 people. By 2000, the number had jumped to 8 percent, or 275,315 people.

In the twenty-first century, Latinos are the largest minority in Oregon. Census data reports that the Latino population in Oregon increased 144 percent between 1990 and 2000. By 2003, the permanent Latino population had risen to 9 percent of the state’s total population, or about 320,200 people. Based on 2013 census, almost 500,000 Latinos lived in Oregon, about 12 percent of the population—the fourteenth largest number of Latinos in the nation. Of those who identify as Latinos, 63 percent were born in the United States. In Oregon, 85 percent of Latinos are of Mexican origin, with the remaining 15 percent primarily from Guatemala, Puerto Rico, Cuba, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, unauthorized immigrants comprised roughly 5 percent of Oregon’s workforce in 2010, or about 110,000 people.

Author's note: Latino refers to persons who live in the United States and trace their ancestry to Latin America or, in some cases, the Caribbean or Spain. The term “Latino” was included for the first time in the 2000 census. In that census, people of Spanish/Hispanic/Latino origin could identify as Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or “other Spanish/Hispanic/Latino.” In the 2010 census it was noted that, “for this census, Hispanic origins are not races.” This information was gleaned from Lynn Stephen, The Story of PCUN and the Farmworker Movement in Oregon. Revised edition. Eugene, Ore.: Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies, 2012, p. 6.

-

![Manuel Vasquez in the fields. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection.]()

Manuel Vasquez .

Manuel Vasquez in the fields. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

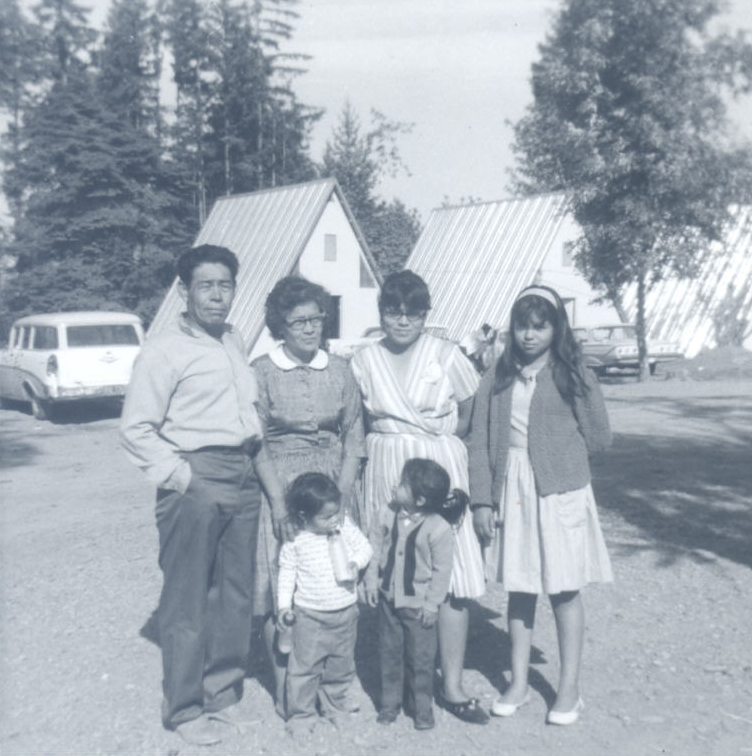

![L. Fidel, Maria, Maria Stella, Ophelia, Marisella (child on left) and unknown friend. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection.]()

A family living at Wilson Camp.

L. Fidel, Maria, Maria Stella, Ophelia, Marisella (child on left) and unknown friend. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![Unknown members of a migrant family. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection.]()

Unknown members of a migrant family.

Unknown members of a migrant family. Part of the Valley Migrant League Collection. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Alberto Salazar (1958 - )]()

Alberto Salazar (1958 - )

A charismatic distance runner who set one world and six United States r…

-

![Bracero Program]()

Bracero Program

The Mexican Farm Labor Program, also known as the Bracero Program, was …

-

Buckaroos

For over a century-and-a-half, buckaroos have done the work on the ranc…

-

![Centro Cultural de Washington County]()

Centro Cultural de Washington County

Centro Cultural de Washington County is an educational and cultural cen…

-

Charrería

Charrería is a Mexican sport that involves skillful roping, talented ho…

-

![Colegio César Chávez]()

Colegio César Chávez

Colegio César Chávez, located in Mt. Angel in the lower Willamette Vall…

-

![Eva Castellanoz (1939- )]()

Eva Castellanoz (1939- )

Eva Castellanoz—traditional artist, curandera (healer), activist, and t…

-

![Joaquin "Chino" Berdugo (1850-1931)]()

Joaquin "Chino" Berdugo (1850-1931)

Joaquin “Chino” Berdugo was a prominent vaquero leader and stockman in …

-

![Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN)]()

Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN)

Founded in April 1985, the Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (th…

-

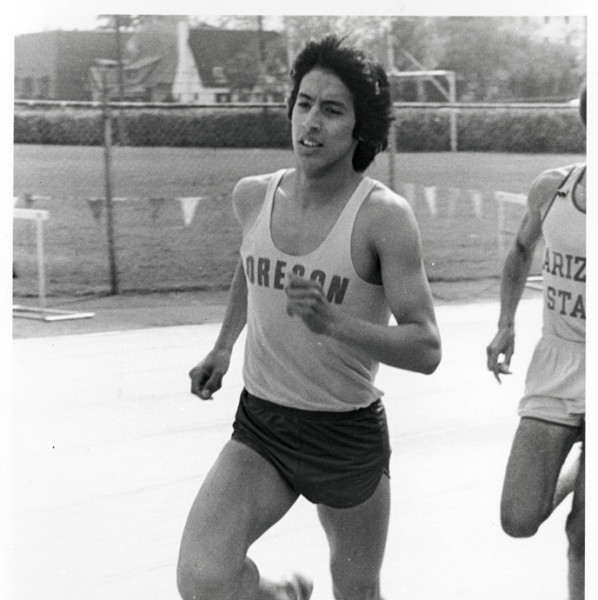

![Rudy Chapa (1957-)]()

Rudy Chapa (1957-)

“Rudy, Rudy,” chanted the fans attending the June 1978 NCAA Track and F…

-

![Susan Castillo (1951-)]()

Susan Castillo (1951-)

Susan Castillo was the first Latina elected to the Oregon State Legisla…

-

![Valley Migrant League]()

Valley Migrant League

From 1965 until 1974, the Valley Migrant League (VML) helped Oregon mig…

-

![Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center]()

Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center

The Virginia Garcia Memorial Health Center was established in 1975 to p…

-

![Woodburn]()

Woodburn

Woodburn has always had a dynamic identity. Located in French Prairie i…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Letter from G.W. Luhr, General Claims Agent, Southern Pacific Company to Honorable Alfredo Elias Calles, Consul of Mexico re death of Ignacio Garnica Espinosa SSN 724-14-5679, March 31, 1945. National Archives and Record Administration Pacific Region, Record Group 211, War Manpower Commission XII, Box 2966, Mexican Track Workers Deaths, January – June 1945.

National Archives and Records Administration, RG 211, Office File of Wartime Commission Representative in Mexico, 1943-1946, Entry 196, Box 3.

Gonzales-Berry, Erlinda V. and Marcela Mendoza. Mexicanos in Oregon: Their Stories, Their Lives. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2010.

Garcia, Jerry, and Gilberto Garcia, eds. Memory, Community, and Activism: Mexican Migration and Labor in the Pacific Northwest. East Lansing, MI: Julian Samora Research Institute and Michigan State University, 2005.

Gamboa, Erasmo and Carolyn M. Baun, eds. Nosotros: The Hispanic People of Oregon. Portland, Ore.: The Oregon Council for the Humanities, 1995.

Compean, Mario. “Mexican Americans.” Columbia River Basin Ethnic History Archives.

Cardoso, Lawrence A. Mexican Emigration to the United States: 1897-1931. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press, 1980.

Maldonado, Carlos S. and Gilberto Garcia. The Chicano Experience in the Northwest. Second Edition. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, 2001.

“New Americans in Oregon: The Political and Economic Power of Immigrants, Latinos, and Asians in the Beaver State.” Immigration Policy Center, American Immigration Council, July 2013 and Pew Research Hispanic Trends Project: “Demographic Profile of Hispanics in Oregon, 2011.”