The Manila Galleon Trade and the Wreck on the Oregon Coast

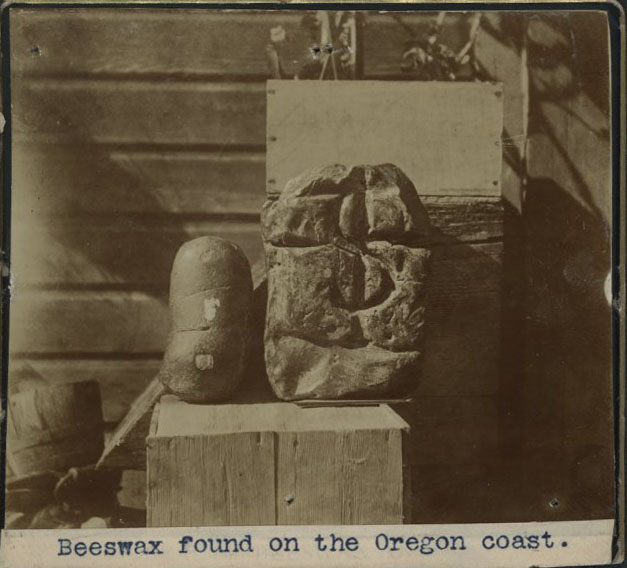

Nehalem-Tillamook and Clatsop peoples, and later EuroAmerican explorers and settlers of what is now Oregon’s north coast, knew that a large ship had wrecked on Nehalem Spit long ago. Archaeological and geological analysis has determined that it was most likely the Santo Cristo de Burgos, the Manila galleon that left the Philippines in the summer of 1693 carrying exquisite Asian trade goods. The ship was headed for Acapulco but was never seen again. Among other things, the wreck left a massive cargo of beeswax blocks, often stamped with shippers’ marks, scattered and buried on Nehalem Spit and in the vicinity of Nehalem Bay.

The Santo Cristo de Burgos was built in 1687-1688 at the Spanish shipyard of Solsogón on the island of Bagatao in the Philippines. The ship’s exact dimensions are not known, but the tonnage of Manila galleons increased over the years, as merchants wanted more cargo space for the lucrative trade to Acapulco. By the mid-seventeenth century, the Philippine shipyards were turning out galleons that had a 1,000-ton cargo capacity. Thus, it is likely that the Santo Cristo de Burgos had between 1,000 and 1,500-ton capacity, which would have been a fairly common size range at the time. Constructing such a large galleon required some two thousand trees, and the Philippines furnished forests of excellent hardwoods, including teak. Conscripted Filipinos did the toughest work of felling and stripping the trees, while other natives and Chinese craftsmen, under Spanish oversight, completed the construction and fittings.

The Manila trade route, maintained by Spain for 250 years (1565-1815), brought exotic Asian trade goods across the North Pacific to Acapulco in New Spain (now Mexico). It was a perilous, storm-ridden journey of some twelve thousand miles. Goods carried by the Manila galleons included embroidered and painted Chinese silks, lacquer furniture, ivory figurines, spices, Chinese fans, and Philippine cottons.

The captain of the Santo Cristo was Don Bernardo Iñiguez del Bayo y de Pradilla, a Basque nobleman from Tudela, Spain, who was baptized in December 1646. A member of the elite Knights of Santiago military order, he went to Mexico in 1686 and was appointed mayor of the Mexican mining town San Luis de Potosí, where he oversaw construction of the town’s first public works project. This was a deep ditch (called La Zanja) that encircled the city, and which was successful in ending the frequent disastrous flooding that devastated the residents. The viceroy of New Spain subsequently commissioned del Bayo to head the mounted cavalry of Mexico City, the position he held at the time of his appointment as galleon captain.

As captain, del Bayo sailed the Santo Cristo de Burgos back to the Philippines from Acapulco in the spring of 1691. The next voyage, leaving the Philippines in the summer of 1692, ended in a return to port, due to losing all three masts in a terrible storm in the San Bernardino Straits area. The Manila trade was the principal economic basis of the Philippines colony, and an unscheduled return to port was a serious financial blow. Spanish authorities conducted an investigation of the disaster, and Captain del Bayo was cleared of responsibility for the mishap.

The Santo Cristo was overhauled and repaired over the winter of 1692-1693. New officers were assigned, as most of the 1692 officers had been imprisoned, banished, or had their maritime careers curtailed as punishment for the calamitous return to port. Captain del Bayo was again in command. The crew included more than thirty artillerymen, who commonly traveled on Manila galleons in case of attack at sea. The rest of the crew numbered under two hundred men. Archival documents indicate that some, including all the officers, were likely Spanish; but most crew were probably Filipino, as was common on Manila galleons. There were also sixteen passengers, including six priests of the Augustinian, Dominican, and Jesuit orders, as well as merchants and military men.

According to correspondence among contemporary Spanish officials, the Santo Cristo de Burgos left the Philippines in 1693 before taking on essential supplies and crew, in order to avoid paying taxes and bonds associated with the 1692 return to port. Captain del Bayo left some thirty members of the crew in port, all of whom were essential on a Manila galleon.

The details of the wreck on the Oregon Coast will never be precisely known, but it most likely took place in the winter season, between November 1693 and February 1694. It is likely that the ship encountered several gales in the North Pacific and then storms closer to the Oregon Coast. The Santo Cristo may have been weakened by inadequate repairs in the Philippines, and the voyage would also have been hampered by deaths from scurvy among the crew. Coastal currents flow northward on the Oregon Coast in winter due to the Aleutian low-pressure systems, so it is likely that the galleon would not have been able to correct course once it got too close to the coast.

Explorers, Fur Traders, and Settlers

John Ordway of the Lewis and Clark Expedition mentioned Clatsop peoples coming to trade “bears wax” with the expedition members. Private Joseph Whitehouse’s entry for March 9, 1806, confirmed that the Clatsops were trading beeswax: “Sunday, March 9th. Several of the Natives came to the fort. They brought with them Some Small fish, Bees Wax &ca to trade with us.” A few years later, in 1813-1814, fur trader and explorer Alexander Henry also mentioned trading beeswax with Clatsop peoples “where the Spanish ship was cast away some years ago.” Over the decades, there was much speculation among coastal residents about the occasionally visible wreck.

Early Tillamook County settler Warren Vaughn recorded Nehalem-Tillamook oral traditions from the 1850s of the wreck on Nehalem Beach. The only witnesses to the wreck suffered many later shocks from epidemics, conflicts with EuroAmerican settlers, violence, and forced removals. It seems likely that the shipwreck left many survivors who lived next to the Nehalem-Tillamook and may have been dependent on them until misunderstandings and tensions caused them to kill the castaways.

Silas B. Smith, grandson on his mother’s side of Clatsop chief Coboway and son of pioneer Solomon Smith, wrote the longest account of the “Beeswax wreck,” as it was called. “Sometime ago, before the coming of the whites,” he wrote in his influential essay, published in 1899, “a vessel was driven ashore in the vicinity of where the beeswax is now found….The vessel became a wreck, but all or most of her crew survived….The crew…remained there with the natives several months, when by concerted action the Indian masacred [sic] the entire number, on account, as they claimed, that the whites disregarded their—the natives’—marital relations. The Indians also state in connection with the massacre, that the crew fought with slung-shots [sic]. It would appear from this that the [survivors] had lost their arms and ammunition.”

The Galleon Wreck and Treasure Hunting

This one ship, out of approximately three thousand shipwrecks on the Oregon Coast, has seized the imaginations of Oregonians. That may be because the ship was enormous by contemporary standards, judging by accounts of those who saw portions of it on the beach or at low tide, and its cargo included Asian porcelains and tons of beeswax—so much that early settlers mined the buried beeswax blocks and sold them for profit. Also, because the wreck occurred before EuroAmerican settlement and there was no information about it other than Native oral tradition, many stories sprang up to explain the ship’s fate.

Once EuroAmerican settlers built communities on the north coast, the cultural transmission of the tradition began to take on new facets. Early newspaper accounts, often purporting to quote “an old Indian” or “an old Indian woman” for authenticity, increasingly focused on the wreck as a treasure ship. Some tellers and newspapers conflated the shipwreck with a less-identifiable account of a ship that anchored offshore, from which men rowed ashore and buried a box near Neahkahnie Mountain—in some versions killing a crew member and leaving his body atop the buried box—before rowing away. Warren Vaughn mentioned the two traditions as separate, the latter having occurred more recently than the galleon wreck; but Samuel J. Cotton’s Stories of Nehalem, published in 1915, contained an account that conflated the two tales. Thomas Rogers, a McMinnville writer, was especially enthusiastic in writing tales about swashbuckling mariners, pirate ships, gun battles, romance, and hidden treasure, frequently focused on Neahkahnie Mountain and including a Spanish wreck as a set piece.

The result was that the Neahkahnie Mountain area and the beaches of Nehalem Spit became the state’s premier locus for treasure-hunting. Samuel G. Reed, a Portland businessman who created a development on the flanks of Neahkahnie Mountain, encouraged residents and visitors to dig for treasure, and treasure-hunting continued from the mid-nineteenth century until the late twentieth on both private and public lands. The seaward part of Neahkahnie became part of Oswald West State Park in the 1930s. From 1967 to 1999, the period when Oregon’s Treasure Trove law required a permit for treasure-seeking on state-owned lands, 93 percent of the applications focused on the Neahkahnie area.

The best-known nineteenth-century treasure hunter was Patrick Smith, the son of Hiram Smith of Bay City. Patrick Smith was known in the Manzanita area for his persistent treasure hunting, but there were many other seekers as well. Some dug trenches or deep pits, and others used hydraulic hoses in their search for treasure. Tony Mareno, a Salem house painter whose real name was Ed Fire, focused on the beach, often using heavy equipment, ranging from bulldozers to drill augurs, in his searches. Others, such as the Tillamook Treasures group and seekers Bud Kretsinger and Lloyd Grimes, thought the treasure was more likely on the flanks of Neahkahnie. Most seekers had a Spanish angle to their theories of where treasure might be hidden, ranging from interpretations of purported Spanish markings on stones to clues pointing toward Spanish colonial explorations in this distant northwest region.

A smaller number of seekers were interested in the galleon itself, beginning with E.M. Cherry, the British vice-consul in Astoria. In the 1930s, he considered excavating a visible part of the wreck as a tourist concession but abandoned the plan when it proved too expensive. Bill Warren sought to locate the underwater portion of the wreck in the 1980s. His relationships with state and local officials were prickly, however, and the state refused to grant him a permit. In 1998, just before the Treasure Trove law was repealed, LaVerne Johnson sought unsuccessfully to negotiate a contract with the state for a division of the treasures he hoped to locate on the wreck.

The Galleon in Oregon and Coastal History

The wreck of the Santo Cristo, if it is ultimately determined to be the ship that wrecked on Nehalem Spit, remains an object of Oregonians’ fascination in the twenty-first century. The details of the long-ago tragedy, taking place in a very different pre-modern world, will always remain a matter of speculation, but archival research and Native oral tradition have given us the outline of the events that led to the disaster. The enormous amount of beeswax on board the ship, scattered across Nehalem Spit in large bundles and blocks, kept the mysterious ship in people’s minds and still evokes wonder. A vast web of fables about treasure from the ship, pirate activity, and maritime tragedy continues to allure enquirers with mesmerizing folklore.

Though treasure-hunting is no longer allowed on state lands, archaeologists are continuing the search for the galleon’s remains. Visitors can see items from the wreck in regional museums: a small silver holy oil jar, an exquisite arrowhead of Chinese porcelain crafted by Nehalem-Tillamook artisans, and a block of beeswax are on permanent display at the Tillamook County Pioneer Museum. The Columbia River Maritime Museum in Astoria has in its collections beeswax and a rigging pulley from the wreck found at the end of the nineteenth century. In June 2022, timbers located in a cove just north of Neahkahnie Mountain were removed to the Museum for further testing. Initial tests indicated they dated from the time period of the Santo Cristo de Burgos. For all these reasons, Oregonians continue to be fascinated by the Manila galleon that came to grief on or near Nehalem Spit centuries ago.

-

![]()

A Manila galleon (left) moored in Manila Bay trading with a Chinese junk (right).

Courtesy of the artist, Roger Morris

-

![]()

The Manila Galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción at sea..

Courtesy of the artist, Roger Morris

Related Entries

-

![Beeswax shipwreck]()

Beeswax shipwreck

Since the earliest days of EuroAmerican settlement on the Oregon Coast,…

-

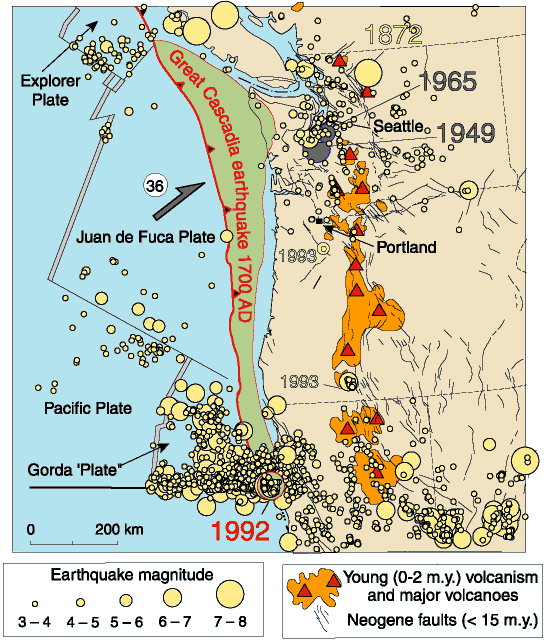

![Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Cascadia Subduction Zone]()

Earthquakes and Tsunamis in the Cascadia Subduction Zone

Sometime in the future, the Pacific Northwest, including Oregon, Washin…

-

![Hobsonville Indian Community]()

Hobsonville Indian Community

The Hobsonville Indian Community was a Native settlement on Tillamook B…

-

![Neahkahnie Mountain]()

Neahkahnie Mountain

Neahkahnie Mountain, about twenty miles south of Seaside, is a prominen…

-

![Nehalem Bay State Park]()

Nehalem Bay State Park

Nehalem Bay State Park occupies almost 900 acres on a sand spit separat…

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Frankowicz, Katie. "Long-sought Spanish Wreckage Found by Fisherman," Chinook Observer, June 22, 2022.

Fish, Shirley. The Manila-Acapulco Galleons: The Treasure Ships of the Pacific. AuthorHouseUK, 2011.

Giraldez, Arturo. The Age of Trade and the Dawn of the Global Economy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015.

Pérez-Mallaína, Pablo. Carla Rahn Philipps, trans. Spain’s Men of the Sea: Daily Life on the Indies Fleets in the Sixteenth Century. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 2005.

Schurz, William Lytle. The Manila Galleon. Boston, Mass.: E.P. Dutton, 1959.

Smith, Silas B. “Tales of Early Wrecks on the Oregon Coast, and How the Beeswax Got There.” Oregon Native Son 1 (January 1900): 443-446.