Flowing 113 miles westward from the Blue Mountains, the North Fork John Day River drains a 1,850-square-mile section of north-central Oregon. Included in the Oregon Scenic Waterways Program and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, the North Fork hosts the largest spawning population of wild spring chinook and summer steelhead in the Columbia River system.

The North Fork’s corridor has long been important to southern Plateau Indians and their ancestors. The river’s watershed is within the ceded boundaries of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation, and the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs have a long tradition of using riverside sites for fishing, hunting, camping, root digging, and berry picking.

The lure of gold brought miners to the North Fork as early as 1855. Active mining of the gravel and sands of the river and its tributaries, using a process known as placer mining, began in earnest in 1861 at places such as Otter Bar (near Dale) and above Desolation Creek. Larger-scale placer and lode mining in the 1880s lasted into the 1950s, and one study suggests that the North Fork produced nearly two million dollars in gold by 1914. Placer mining significantly changed the river’s fabric and flow, displacing two to three million cubic yards of river deposits through the use of dredges, draglines, flumes, and floating wash plants. Mining continues on a small scale on the North Fork through recreational panning, handwork, small-scale placer exploration, and small suction dredges. Remnants of the river’s mining past can be seen in abandoned cabins and mounds of tailings piles.

The discharge of the North Fork, including the tributary Middle Fork, averages about 1,300 cubic feet per second, as measured by a stream gage at river mile 15.3, just downstream from Monument. The discharge ranges from 120 to 3,650 cubic feet per second through the year, with highest discharge in the months of April and May, when snowmelt is at its highest across the basin.

Establishment of the 121,800-acre North Fork John Day Wilderness in 1984 protected key sections of the river’s headwaters and drainage. In 1988, Congress passed the Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which designated almost half of the North Fork as wild and scenic. That same year, Oregon Ballot Measure 7, the Oregon Rivers Initiative, designated a section of the North Fork, from Big Creek to Monument, as an Oregon State Scenic Waterway.

The North Fork is designated a national wild and scenic river for 54.1 miles, from its headwaters in the Baldy Creek Unit of the North Fork John Day Wilderness to its confluence with Camas Creek, west of Dale. It possesses all three national wild and scenic river classifications: wild, scenic, and recreational. The first 3.5 miles of the river is classified as wild, followed by 7.5 miles classified as recreational, as the river bends west. At Trail Creek, the river returns to wild status for 24.3 miles, carving a broad loop through the heart of the wilderness along the North Fork John Day Trail Hiking Trail. At Big Creek, the classification changes to scenic for 10.5 miles to Texas Bar Creek, and the 8.3-mile stretch to Camas Creek is classified as recreational. Between Camas Creek and Monument, the Middle Fork enters the river, and the adjacent landscape transitions to open ponderosa pine forest, to savannah, to high desert sage and juniper ranchland, continuing to its confluence with the John Day River near Kimberly.

The U.S. Forest Service, through the Umatilla and Wallowa–Whitman National Forests, manages the river’s wild and scenic portions and adjacent forest and wilderness areas, and the Bureau of Land Management provides camping opportunities and boating access on the lower river. Popular recreational activities on the North Fork include fishing, floating, camping, hiking, and recreational gold panning. On the North Fork John Day Trail, near the river’s confluence with Trout Creek, sits the Home Mines Cabin, featured as the Bigfoot Hilton in William L. Sullivan’s account of his solo backpacking trek across Oregon, Listening for Coyote.

-

![]()

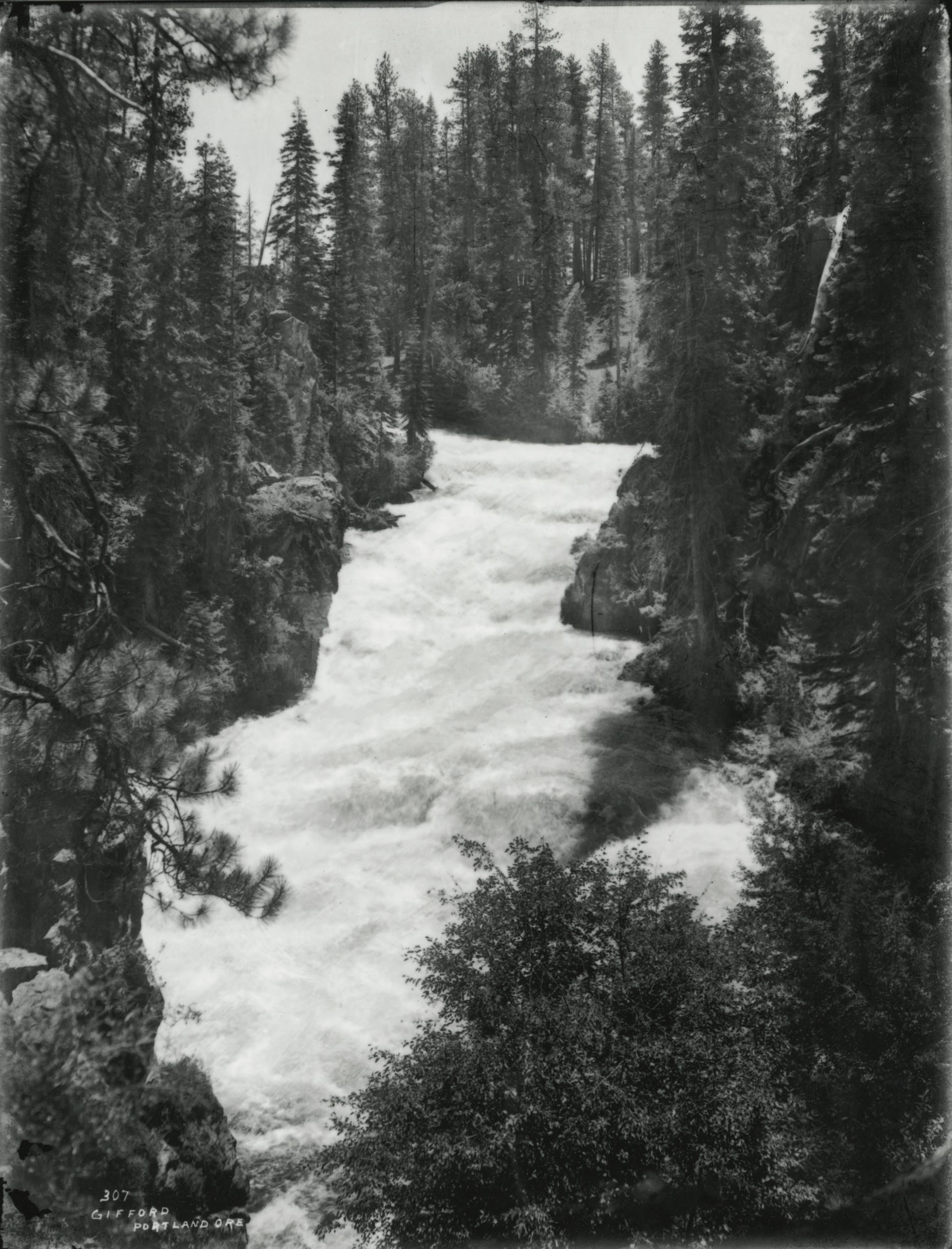

North Fork John Day River, near Monument, Oregon, 2008.

Courtesy USGS, photo by Patrick Miller

-

![]()

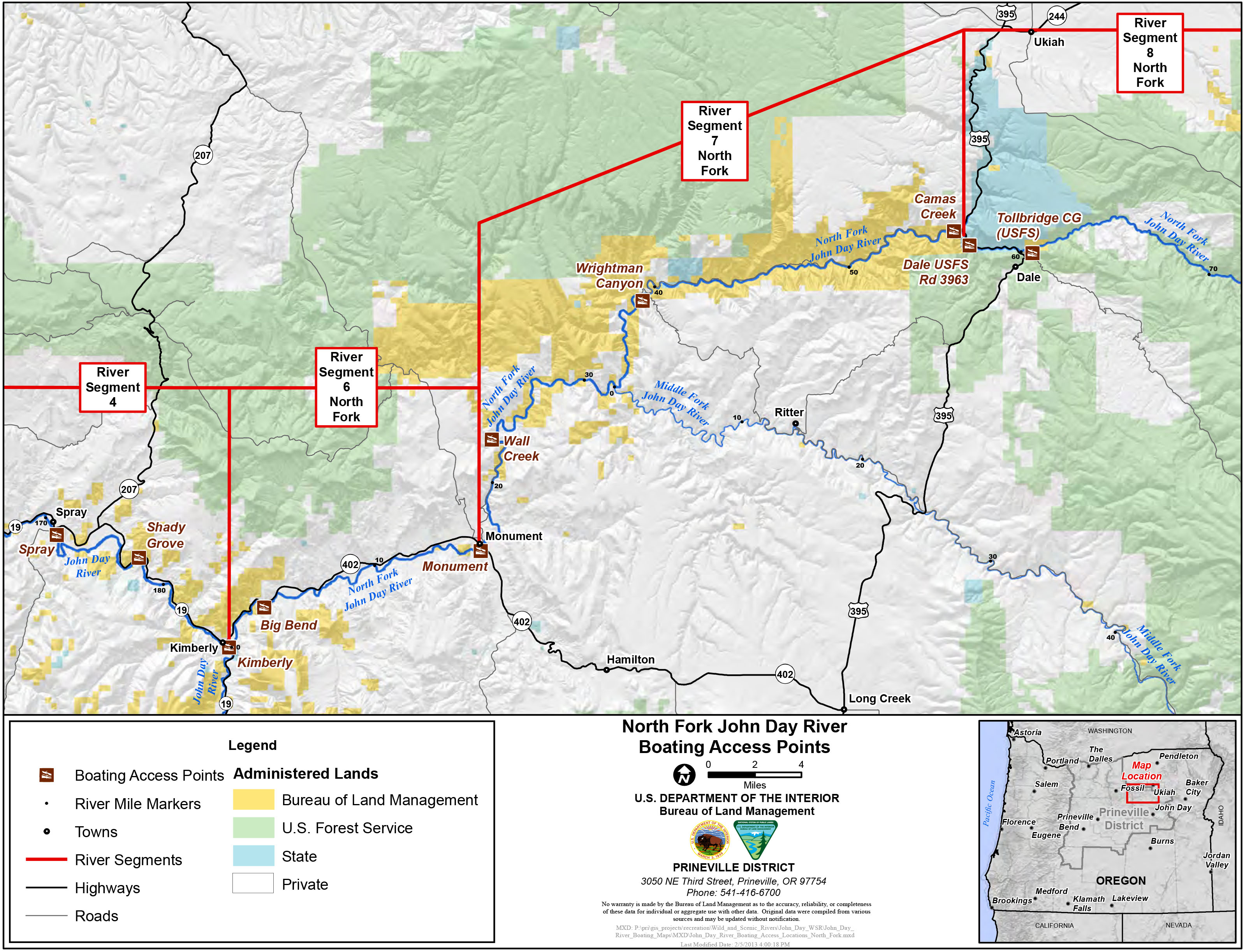

BLM access map to the North Fork John Day River.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management,

Related Entries

-

![Blue Mountains]()

Blue Mountains

The Blue Mountains, perhaps the most geologically diverse part of Orego…

-

![John Day River (north-central Oregon)]()

John Day River (north-central Oregon)

The 281-mile-long John Day River in north-central Oregon is the longest…

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![South Fork John Day River]()

South Fork John Day River

From its headwaters in the fir and ponderosa pine forests of Grant and …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Palmer, Tim. Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Corvallis, Ore.: Oregon State University Press, 2014.

Sullivan, William L. Listening for Coyote: A Walk Across Oregon's Wilderness. Corvallis, Ore.: Oregon State University Press, 2000.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, John Day River (North Fork), https://www.rivers.gov/rivers/john-day-nf.php, accessed January 8, 2018.

U.S. Forest Service. Decision Notice and Finding of No Significant Impact, Environmental Assessment for the North Fork of the John Day Wild and Scenic River Management Plan, 1993.