Populism refers to a political discourse that defines the interests of “the people”—as opposed to those of political, economic, or cultural elites—as well as to a concrete political movement of the late nineteenth century dedicated to restraining corporate power and influence and reinvigorating American democracy. The national movement was rooted in rural economic discontent and the organizing efforts of the National Farmer’s Alliance and Industrial Union, which took hold particularly among cotton- and grain-producing farmers in the South and the Great Plains in the 1880s. When the movement spread to Oregon in 1891, it gave political shape to longstanding frustrations felt by farmers and workers in Portland and across the state.

Oregon’s experience with populism at the end of the nineteenth century in many ways reflected the national movement. But it did more than that. It helped define the state’s political culture bequeathing Oregonians with the system of direct democracy, an electoral set of tools that would fulfill some of the goals of the Populist movement. They would also serve other, later movements that adopted the rhetorical strategies of populism, but with profoundly different programs.

The National Movement

The National Farmers Alliance responded to the travails of farmers in the South and Great Plains who were suffering from low commodity prices and high interest and transportation rates charged by bankers and railroads. The Alliance first sought to develop cooperative businesses that would help farmers market their crops. When cooperatives failed, the Alliance turned to governmental action, particularly a subtreasury plan devised by Texan Farmers’ Alliance leader Charles Macune, who called on the federal government to intervene in agricultural and currency markets. The plan recommended that warehouses hold crops until they rose in price, while they also served as collateral for low-interest loans issued in government-backed paper money.

It was the call for federal action that led the Farmers’ Alliance to join with other reformers, many of whom were affiliated with the Knights of Labor, to establish the People’s Party. At their 1892 convention in Omaha, Nebraska, Populists—as those affiliated with the People’s Party were known—adopted a platform that included Macune’s subtreasury plan, the nationalization of railroad and communications monopolies, the replacement of bank notes with government-issued paper currency, the treasury’s free and unlimited coinage of silver, the direct election of senators and other officials, an income tax, and opposition to the use by capital of private militias. Politically and economically, Populists posed a democratic response to the inequalities in power and wealth that had emerged during the decades after the Civil War (the "Gilded Age").

Though Populists came from varying backgrounds, they shared an understanding of economics grounded in enlightenment political economy. They believed that labor is the source of all wealth and that workers are due the fruit or reward of their labor. To Populists, the high transportation and interest rates imposed by railroads and banks appeared to be a transfer from those who did the work to those who manipulated the labor, and the resulting impoverishment of workers and farmers and the concentration of wealth and power in corporations threatened republican government.

Populism and the Farmers' Alliance in Oregon

In Oregon, the Populist movement built on these understandings and frustrations. Farmers in the Willamette Valley, for example, had long suffered at the hands of transportation monopolies and credit markets. They had responded, first under the aegis of the Oregon branch of the Patrons of Husbandry (the Grange), established in 1873, and then under a series of independent reform movements. These organized farmers attempted to enact legislative controls on railroad policies to lower the cost of shipping farm commodities. They also sought to lighten the tax burden on landed property by taxing the interest earned by bankers and other creditors, most of whom extended mortgages to Oregon farmers and lived outside the state. The tax was an effort to tap income-generating investment property and to alleviate the burden on producers.

Such efforts were weakened in the legislature and were subject to judicial review as the federal courts increasingly diminished the state’s authority over transportation systems that had more than local impact and over creditors who were not residents of the state. These efforts, frustrated by the Portland-centered Republican Party and the federal judiciary, laid the groundwork for the Farmers’ Alliance and the People’s Party.

In 1891, local chapters of the Farmers’ Alliance spread among Willamette Valley farmers. The movement also gained support in southern Oregon in such places as Jackson County, where farmers who had previously been aloof from their Willamette Valley brethren were given an institutional outlet for their growing frustrations with corporations and corrupt politicians. The local chapters acted as a social and educational society. Lecturers from the national organization prepared Oregonians for political insurgency, and local men and women lectured and debated ways to reform government and improve the economic and social position of farmers. Members of the Oregon Farmers’ Alliance called on urban and rural labor to unify to “encourage and foster agricultural and mechanical pursuits, provide a just and fair remuneration for labor, and a just exchange of our commodities.”

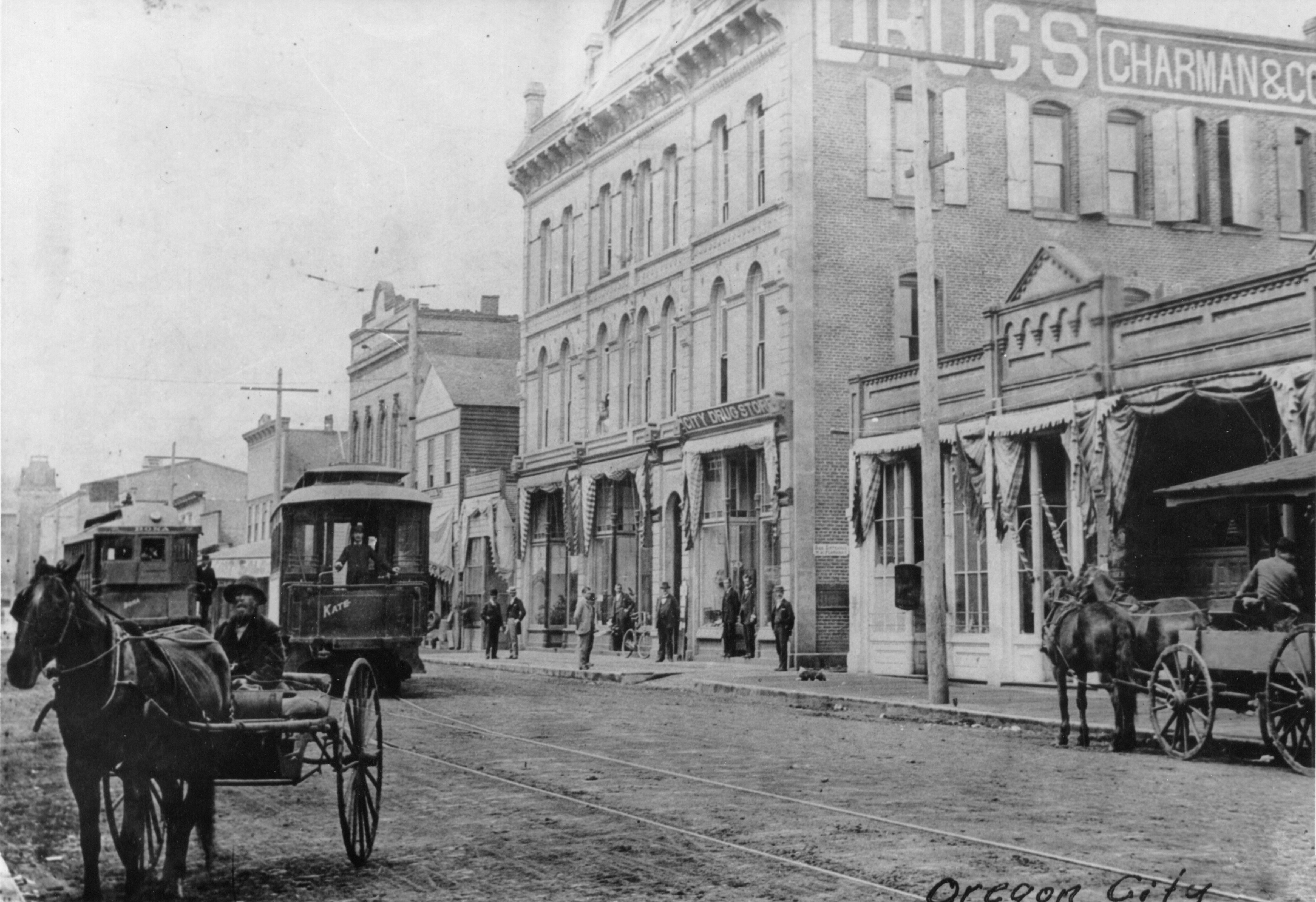

After months of organizing efforts, members of the Farmers’ Alliance gathered in Oregon City in March 1892 to found the Oregon People’s Party. The state organization adopted much of what would become the Omaha Platform of the national party and also addressed local concerns, including abolishing the state railroad commission and replacing it with a maximum-rate law, which promised to reduce freight rates by one-third. With the aim of extending their access to markets and reducing their reliance on railroad monopolies, the Oregon People’s Party called for the federal government to improve the Columbia River, including the building of a federally operated railroad to compete with the Northern Pacific. Reflecting the influence of single-taxers, the party faithful called for a graduated land tax and an end to land speculation. The party also sought to close a loophole that had allowed the urban wealthy to diminish their tax liability.

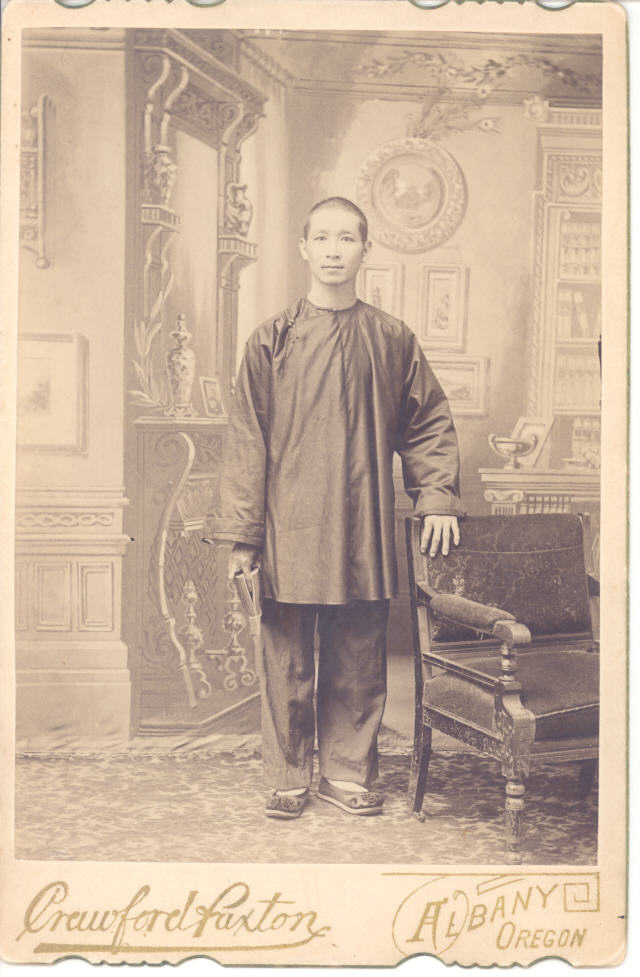

The Knights of Labor and Anti-Chinese Sentiment

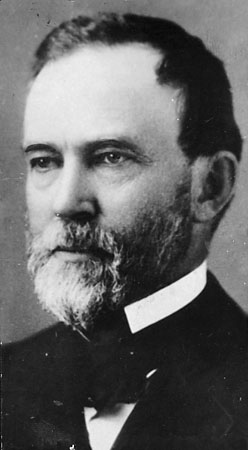

Populism also built on earlier efforts of urban workers to challenge the prerogatives of capital. Some of this had taken on an ugly form in the 1880s, as Knights of Labor organizers in Portland and elsewhere agitated for the removal of Chinese workers from Oregon workshops and factories. This movement fused a racial hatred of the Chinese with an opposition to monopolistic corporations that agitators believed used Chinese labor to degrade “white” labor and turn it into “wage slavery.” Some of those who led this effort would become leaders in Populist politics. Sue Ross Keenan, who called for the removal of Chinese in 1886, was nominated as the People’s Party candidate for school superintendent in 1892; she outpolled other People's Party nominees for local office. Daniel Cronin, the Knights of Labor organizer who had worked hard to fuse that organization’s anti-monopoly vision with Chinese removal, would become an influential leader in the Multnomah County People’s Party, one who fought to keep the local party loyal to the Omaha Platform instead of the more pragmatic strategy of fusion with the Democrats. The most visible link between Populism and the anti-Chinese movement was Governor Sylvester Pennoyer, who declared himself a Populist in 1892.

Legislative Reforms

For the most part, working-class Populists left behind the racial politics of the 1880s and focused instead on issues directly related to labor organization. The Multnomah County Convention of 1892 called for an eight-hour work day, supported the anti-Pinkerton provisions of the state platform (a reaction to corporations using detective agencies as private militias to break strikes and intimidate labor), and advocated the labeling of products produced by convict labor. The platform also called for tax reforms and the election of police and fire commissioners. Preparing for the city election of 1892, Portland Populists extended the demands of urban workers, calling for a free bridge across the Willamette River, a free employment office, free boardinghouses for the poor, and municipal ownership of local providers of electricity, water, and transportation.

At its founding, then, the People's Party of Oregon drew from diverse sources and experiences, some of them the same as the national party and some of them peculiar to local experience. And there were signs of strength. In 1892, People’s Party presidential candidate James Weaver received 40.5 percent of the vote in Oregon, and Populist tickets ran particularly well in Jackson, Klamath, Lake, Union, and Wallowa counties. In general, however, the party struggled to gain influence.

Frustrated by Republican hegemony, Populist legislators were unable to turn party measures into law. By 1896, such frustration led to a significant division between “midroaders,” who sought to maintain an independent ticket dedicated to the Omaha Platform, and “fusionists,” who sought to ride the growing enthusiasm for the free and unlimited coinage of silver. That meant lining up behind William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee for president, and supporting Pennoyer as Portland mayor. The midroaders found some success when the two Populist candidates for Congress came close to victory and a number of the party’s candidates were elected to the state legislature.

Though the People’s Party became a casualty of fusion and the 1896 election, Populist influence did not fade.

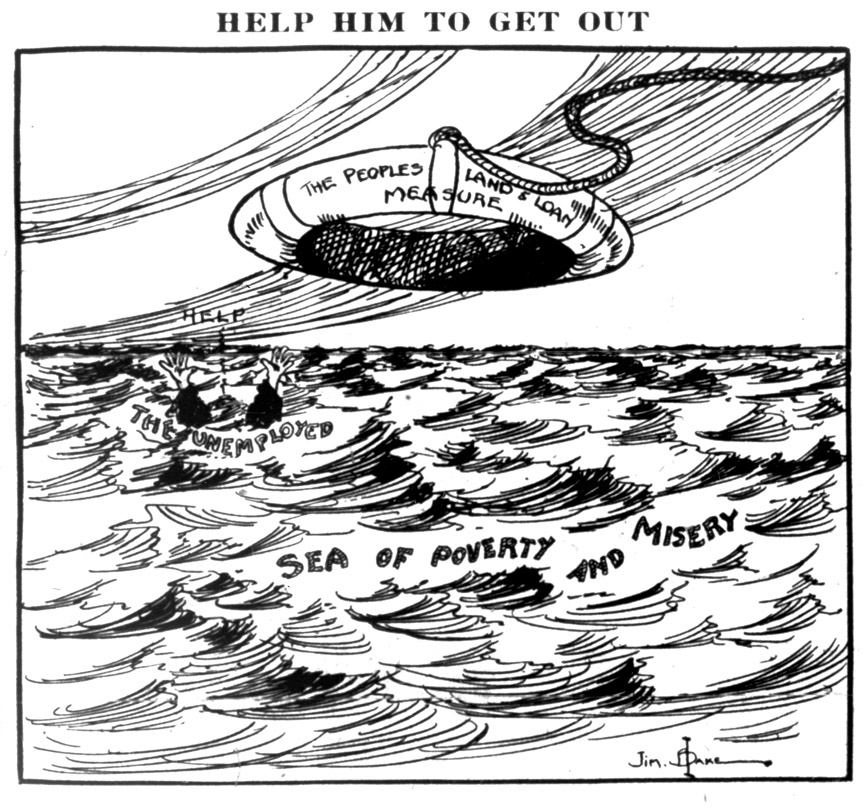

Some of the leadership had been taken with Henry George’s single tax, which sought to tax the "unearned increment" of land values that they believed accrued to the owner as a result of the labor and productivity of others. In fact, single-taxers sought to impose a tax to socialize the “unearned increment” of rising land values enjoyed by land speculators who kept their land out of production. This tax, they believed, would force land into more productive uses so that owners could afford to pay the tax. Single-taxers believed that this increase in overall productivity would stimulate the demand for labor, thereby lowering unemployment and raising wages.

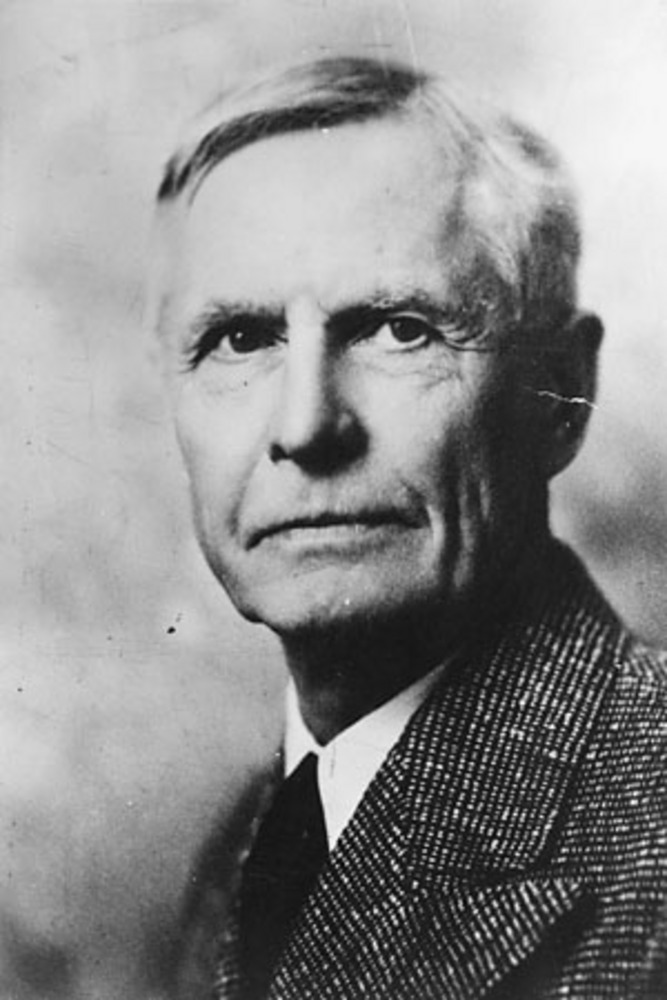

Among the leaders of the single-tax movement was William S. U’Ren, a Populist who had become convinced that the people could not rely on the state legislature, which was easily corrupted by corporate lobbyists and political hacks. U’Ren sought the remedy of direct democracy, and the campaign for that change in the state constitution would be one of the most important results of Populist influence in Oregon.

U’Ren allied the Populists with Jonathan Bourne, a silver Republican who, like many Democrats, sought the kind of expansion in the money supply that the monetization of silver would provide, as opposed to the more extreme Populist call for a government-issued paper currency. Together, they conspired to prevent the Oregon legislature from organizing itself in 1898 so that a “goldbug” Republican (those who fought any expansion of the nation’s currency) would not be elected to the U.S. Senate. This effort resulted in what is known as the “hold-up legislature,” which further disenchanted the midroaders among the Populist faithful who worried that their party was adopting the corrupt methods they so disdained in the mainstream parties.

Nonetheless, U’Ren’s labors bore fruit. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Oregon adopted the tools of direct democracy—the initiative, the referendum, the recall, and the direct election of United States senators. Once in place, those democratic instruments allowed a much more participatory democracy, and U’Ren and his allies used them in a number of unsuccessful ballot measures that aimed to enact the single tax into law.

Direct democracy brought other longstanding Populist issues to voters. Rural and urban working people challenged efforts to build an infrastructure for elite tourism amid the splendor of Oregon’s natural environment. Battles over access to fish had long roiled commercial fishermen. At first, the aim was to create opportunities for working people rather than large fishing interests. In 1890, the Columbia River Fishermen’s Protective Union, an organization of gillnet fishermen, endorsed Governor Pennoyer’s efforts to ban fixed gear, charging that the owners of those fishing methods were monopolists; and in 1895, the Oregon People’s Party adopted a plank in its platform calling for the elimination of fish wheels, seines, and traps. Commercial fishermen used the petition process to put measures on the ballot challenging the closure of rivers by the Fish and Game Commission, an agency that often tried to accommodate wealthy sportsmen eager to preserve tourist-friendly rivers.

Other populists deployed the tools of direct democracy in ensuing years. The Grange, often supported by organized labor, fought a Progressive Era battle to end the use of tax revenues for the building of scenic highways and to have the state highway commission focus on the building of “market roads” that would facilitate trade between city and farm.

In this way, the Populist insurgency of the late nineteenth century bequeathed Oregonians a means to expand the people’s engagement in lawmaking. And while there would be strong echoes of the People’s Party in the Progressive Era use of direct democracy, very different aims would eventually motivate the Ku Klux Klan and, later, the religious right, both of which separated Populist style and discourse from its substantive attack on corporate power. Such movements would define the “people” against powerful elites, but in these cases those elites were rarely defined as corporations. The Klan focused on the power wielded by the Catholic Church or by Jewish bankers, while more recent efforts by right-wing activists organized in Oregon Taxpayers United or in the Oregon Citizens’ Alliance demonized intellectual and cultural elites whom they claimed did not understand common people.

-

![]()

William S. U'Ren, 1946.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN 01831

-

![]()

Sylvester Pennoyer.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Library, ba018278

Related Entries

-

![Chinese Americans in Oregon]()

Chinese Americans in Oregon

The Pioneer Period, 1850-1860 The Cantonese-Chinese were the first Chi…

-

![Expulsion of Chinese from Oregon City, 1886]()

Expulsion of Chinese from Oregon City, 1886

On February 22, 1886, approximately forty men gathered in Oregon City a…

-

![Ku Klux Klan]()

Ku Klux Klan

Fiery crosses and marchers in Ku Klux Klan (KKK) regalia were common si…

-

![Single Tax]()

Single Tax

Virtually unheard of since World War I, the single tax was arguably the…

-

![Sylvester Pennoyer (1831-1902)]()

Sylvester Pennoyer (1831-1902)

Sylvester Pennoyer was a Democratic governor (1887-1895) and mayor of P…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Dodds, Gordon. Oregon: A Bicentennial History. New York, NY: WW Norton and Company, 1977.

Griffiths, David B. Populism in the Western United States, 1890-1900, vol. 1. Lewiston, NY: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1992.

Johnston, Robert. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland Oregon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Lalande, Jeff. “A ‘Little Kansas’ in Southern Oregon: The Course and Character of Populism in Jackson County, 1890-1900.” Pacific Historical Review (1994), 149-176.

Lipin, Lawrence M. Workers and the Wild: Conservation, Consumerism, and Labor in Oregon, 1910-30. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Lipin, Lawrence M. and William Lunch. "Moralistic Direct Democracy: Political Insurgents, Religion, and the State in Twentieth-Century Oregon. Oregon Historical Quarterly 110 (2009), 514-45.

Robbins, William G. "Town and Country in Oregon: A Conflicted Legacy." Oregon Historical Quarterly 110 (Spring 2009), 52-73.

Schwantes, Carlos. "Unemployment, Disinheritance, and the Origins of Labor Militancy in the Pacific Northwest, 1885-86," in G. Thomas Edwards and Schwantes, eds., Experiences in a Promised Land: Essays in Pacific Northwest History. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1986.