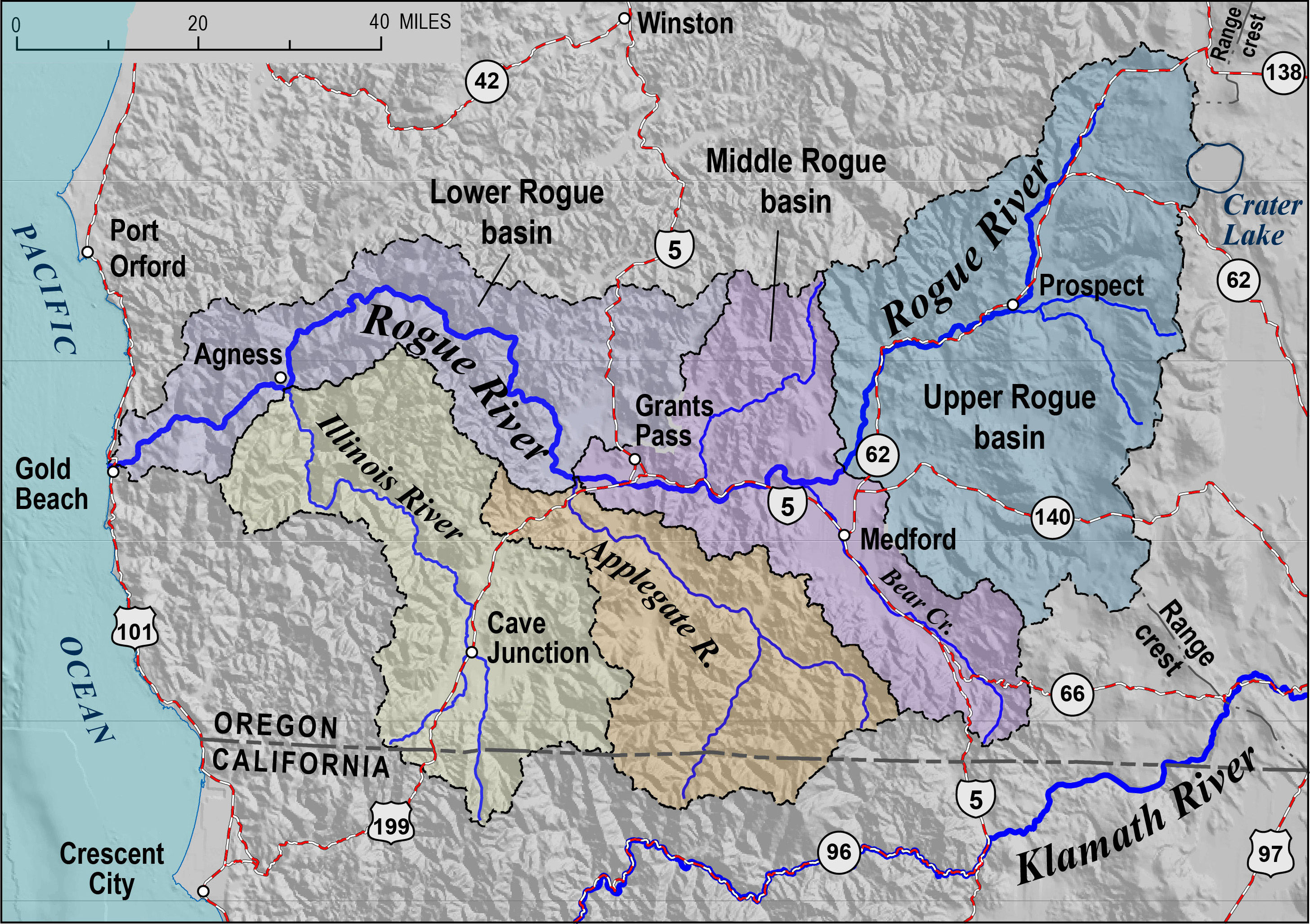

The Rogue River, Oregon’s third-longest river (after the Columbia and Willamette), flows through the southwestern part of the state for 215 miles. Descending from its source high in the Cascade Range, the Rogue reaches the Pacific at the City of Gold Beach. The river’s watershed occupies 5,164 square miles, nearly all of it in Oregon (3 percent is in California). Most of the river’s drainage is in mountainous terrain, although each of the river’s three main tributaries—Bear Creek, the Applegate River, and the Illinois River—flow through valleys with the overwhelming majority of the population, more than 250,000 people. During the 1850s, the Rogue River country was the site of the first gold rush in Oregon as well as the scene of the state’s most bitter conflict between Native people and white settlers, the Rogue River Wars. During the twentieth century, the river gained renown for salmon fishing and challenging whitewater boating.

The natural hydrology of the Rogue River is characterized by high winter and spring flows and markedly lower summer and early-fall flows. The river’s average annual discharge is slightly more than 7,800 cubic feet per second (cfs). The maximum discharge, as measured above the Illinois River at Agness, reached nearly 300,000 cfs during the Christmas flood of 1964. With the Illinois River's discharge of 92,000 cubic feet during the 1964 flood added to that figure, the Rogue's total discharge at Gold Beach would have been close to 400,000 cubic feet per second.

The Rogue River can be divided into three segments—upper, middle, and lower. (Although segment boundaries vary slightly among users, for sports-fishery purposes the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife uses a somewhat different upper/middle/lower segmentation of the river than is used here.) The main stem of the river’s 70-mile-long upper segment follows a generally southward course, beginning at Boundary Springs (at 5,200 feet above sea level) in Crater Lake National Park and ending near the town of Shady Cove. The upper watershed includes two other forks, the Middle Fork and South Fork of the Rogue, which join the main stem (called the Upper Rogue or, less often, the North Fork) near the town of Prospect. All three forks of the Rogue’s upper section flow within steep-walled canyons and lava-rock chasms. One notably turbulent place along the main stem is Natural Bridge, where the river disappears into a lava tube for several hundred feet before emerging downstream. Other significant tributaries on this section of the river include Big Butte Creek and Elk Creek. Most of the drainage area has steep relief and is heavily forested with conifer trees. A large flood-control dam impounds a 10-mile section of the Rogue’s upper segment to create the Lost Creek Lake reservoir.

The middle segment of the Rogue extends from Shady Cove to Hellgate Canyon, downstream from the City of Grants Pass. Flowing generally westward for 64 miles through much gentler terrain, the middle segment has few notable rapids. Little Butte Creek joins the Rogue near Upper Table Rock after flowing through the expansive flatlands of Agate Desert. A short distance downstream, at river mile 126.5, Bear Creek enters the Rogue. Bear Creek Valley, extending to the southeast, has the best agricultural land in the watershed, as well as the cities of Central Point, Medford, Jacksonville, Phoenix, Talent, and Ashland. Extending immediately north from the river, opposite the mouth of Bear Creek, Sams Valley is smaller. Below Table Rock, a steeper terrain bounds the river until it reaches Grants Pass, where the landscape opens into an extensive area of gentle, often nearly level land. The Applegate River joins the Rogue a few miles downstream. Collectively, this segment of the Rogue—that is, Agate Desert, Bear Creek Valley, Sams Valley, and downstream past Grants Pass—is called the Rogue River Valley.

The lower segment, from Hellgate Canyon to Gold Beach, follows an 82-mile-long deep-canyon route through the rugged, forested terrain of the Siskiyou Mountains, a sub-range of the far more extensive Klamath Mountains. With challenging whitewater at such locations as Blossom Bar, this segment’s watershed also includes the steep canyon of the lower Illinois River. The Illinois Valley, located well upstream of this confluence, contains the small community of Cave Junction.

The Rogue River passes through successively older geologic formations as it flows to the Pacific. Beginning among some of the youngest rocks in Oregon—the 7,700-year-old pumice deposits from the eruption of Mount Mazama, which created the Crater Lake caldera—the river then cuts into the nearly one-million-year-old volcanic flows of the High Cascades, followed to the west by the earlier and far more eroded volcanic formations of the Western Cascades. Although much of the middle segment’s valleys are capped by thick layers of alluvium (deposited by the river and its tributaries over a half million years ago), beneath those layers are marine sediments dating from 60 to 100 million years ago, predating the initial buildup of the Western Cascades.

After entering the Siskiyou Mountains, the Rogue flows through some of the oldest geologic formations in Oregon, mostly metamorphic rocks that include altered volcanic flows and marine sediments originally deposited on the ocean floor. Subsequently, these deposits were folded, crumpled, and pushed up against the ancient North American continent by plate tectonics, the entire process, which included the late intrusion of magmas that cooled slowly into granitelike rocks in the eastern Siskiyous, spanned between about 100 million and 350 million years ago.

People first entered the Rogue River drainage at least 10,000 years ago. We do not know what these first people called themselves or what language they spoke. In far more recent centuries, Native peoples inhabiting the Rogue River drainage included a group of Southern Molalla along its uppermost stretch, as well as Takelman-speaking Latgawa who ranged downstream to the Table Rocks, Shasta who occupied the southern Bear Creek Valley, and the Takelma from near Table Rocks to well below Grants Pass. Tututni and other groups lived along the lower river. The annual runs of spawning Chinook and coho salmon and steelhead trout in the Rogue provided their most important source of protein, and dugout canoes made from of sugar pine logs enabled transport. According to early written accounts, "Trashit" was one of the Native names for the Rogue.

The first non-Native person known to reach the Rogue River was Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader Alexander Roderick McLeod, who traveled south from the Coquille River to reach the north bank of the lowermost Rogue on January 11, 1827. He wrote in his journal that his Native guides called the river “Toototenez.” He returned north after a two-day visit. A month later, on February 14, 1827, HBC fur trader Peter Skene Ogden reached the Rogue’s south bank. After crossing Siskiyou Pass, he had followed Bear Creek downstream to reach what he called the “Sastise” river. For nearly a month, Ogden’s party trapped the streams of the middle watershed, taking over 500 beaver pelts. By the 1830s, episodes of conflict with the Takelma led HBC French Canadian trappers to call it “Riviere des Coquins” (river of rascals, or rogues), resulting in the present name. Other names for the Rogue on early maps include McLeod’s, Sastey, Gold, and Rouge (likely a cartographer’s spelling error).

Over the years, the Rogue River came to occupy an iconic place in Oregon culture, in part because of dramatic historic events that include the Rogue River Wars and the simultaneous extension of the California Gold Rush into southern Oregon's rugged terrain. The Rogue's early twentieth-century national reputation as a remote fly-fishing paradise also contributed to the popular image of the river.

River Crossings: As farmers and miners moved into southwestern Oregon during the early 1850s, the Rogue River presented a barrier to travel and commerce. A few pulley-system ferries provided early crossings along the middle segment; most were gone well before 1900, replaced by wooden bridges. The last ferry on the Rogue River, at Shady Cove, served travelers on the Crater Lake Highway until 1921. By the late 1850s, the first bridge spanned the river at Rock Point, a rocky narrows about two miles below Gold Hill. In 1919, the current Rock Point Bridge, a graceful concrete structure designed by Conde McCullough, replaced the previous bridges. Between 1880 and 1920, wooden and steel-truss bridges were constructed on the middle segment of the river. Concrete dominated the river’s bridge construction beginning in the 1920s, including McCullough’s Patterson Bridge over the Rogue at Gold Beach (1930) and his Caveman Bridge in Grants Pass (1931).

Effects of Mining: The lower Rogue and two main tributaries, the Applegate and the Illinois, were the locations of substantial placer-gold mining beginning in the 1850s. In particular, large-scale hydraulic mining operations for placer gold grew rapidly after 1870, profoundly affecting fish habitat. Lengthy ditches diverted water from tributary streams to the mines, sometimes greatly reducing the water quantity in smaller creeks. With huge annual volumes of silt discharged by hydraulic mines into the three rivers, reproductive success of salmon declined. A report by state fisheries specialist Cole M. Rivers on various pre-1941 impacts to the Rogue's fish populations states that these three rivers often “ran red” from the mines’ turbid outwash, which coated gravel spawning beds with silty mud.

Fishing: Commercial fishing began on the Rogue when Robert D. Hume established a salmon cannery at the river’s mouth in 1877. Although Hume established fish hatcheries, his near-monopoly on capturing large quantities of salmon did not last. With other gillnetters competing for the take, serious overfishing resulted by 1900. Due to pressure from fish biologists and sportsmen, Oregon banned commercial fishing on the Rogue in 1935. Sports fishing grew in popularity, particularly after western writer Zane Grey promoted the Rogue as an excellent fly-fishing river in the 1920s. In addition to Grey, celebrities who fished the Rogue included President Herbert Hoover and film star Clark Gable, giving the river further cachet as a fly fishing stream. With hundreds of state-licensed fishing guides operating on the Rogue, sports fishing now generates considerable local income.

Navigation: The first successful passage of a watercraft down the Rogue’s lower segment from Grants Pass occurred in 1869. The small boat was built and rowed by William Windsor, who apparently had no other purpose than to be the first to do so. In 1894, two Curry County ranchers brought their boat upriver to Grants Pass to get supplies, a trip that took forty hours and required lining the craft with ropes from shore past rapids and falls. After 1906, when hard-rock gold mines spread along the lower Rogue, miners occasionally received small quantities of supplies from Grants Pass by boat. Log drives (many unsuccessful because of rapids) occurred on the less formidable middle segment of the Rogue between 1885 and 1915; by 1915, most of the easily accessible timber along the river had been cut. Since the 1970s, tourists have taken commercial jet boat excursions through the Hellgate section near Grants Pass and mail boats from Gold Beach to Blossom Bar along the lowermost Rogue. The Wild and Scenic section of the river, from Grave Creek to Foster Bar, has become popular with rafters and kayakers, who have to obtain date-specific permits for most of the boating season. Only expert boaters tackle the whitewater of the Rogue’s uppermost segment.

Dams and Irrigation: Dams on the Rogue River have generated limited amounts of hydroelectric power. In 1902, private companies built the Ament Dam above Grants Pass and the Gold Ray Dam below Bear Creek to generate power. A target of dynamiting efforts by angry fishermen, the so-called fish-killer Ament Dam was removed in 1921. A higher concrete structure replaced the original Gold Ray Dam in 1941; it ended operations in 1972 and was removed in 2010. PacifiCorp continues to operate hydroelectric facilities, built from 1928 to 1933, on the Rogue’s three upper forks: the main fork of the Upper Rogue, the Middle Fork, and the South Fork.

In terms of irrigation supply, water has been diverted from smaller tributaries of the Rogue’s middle segment. The exception is the Savage Rapids Dam, built in 1921 upstream from Grants Pass, which took water directly out of the river. The dam was removed in 2009 to improve fish passage, and irrigation water is now provided by riverside pumps. During the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation aided Bear Creek Valley irrigators by building higher dams on the Rogue's middle-segment tributaries, the North Fork of Little Butte Creek (at Fish Lake) and in the upper Bear Creek Valley (at Emigrant Lake), where earlier dams (built in the 1920s by local irrigation districts) no longer provided sufficient water to meet the need of orchardists and others.

Because of the periodic propensity for highly destructive floods on the Rogue, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built two large flood-control dams during the 1970s and 1980s, the Lost Creek Dam (officially named the William L. Jess Dam) ten miles above Shady Cove and the Applegate Dam on the upper stretch of the Applegate River. The two reservoirs provide recreational facilities and cooler water for fish during summer months. The Corps planned a third Rogue Basin Project dam on Elk Creek, but it was halted in midconstruction due to environmental impacts on anadromous fish. The Rogue now flows free of dams along the 146-mile stretch from below Lost Creek Dam to the ocean.

Wild and Scenic River: The U.S. Congress designated most of the Rogue’s lower segment as a Wild and Scenic River in 1968, and whitewater rafting, kayaking, and fishing from drift boats bring thousands of recreationists to the Lower Rogue Wild and Scenic River each year. The Wild Rogue Wilderness, established in 1978, and the forty-mile-long Lower Rogue River Trail attract hikers to explore much of the lower river’s canyon. The Upper Rogue Wild and Scenic River, designated in 1988, receives far less use due to its many hazards, but its entire length is paralleled by the forty-mile-long Upper Rogue River Trail, which is easily accessible from the Crater Lake Highway and brings thousands of visitors to the river.

-

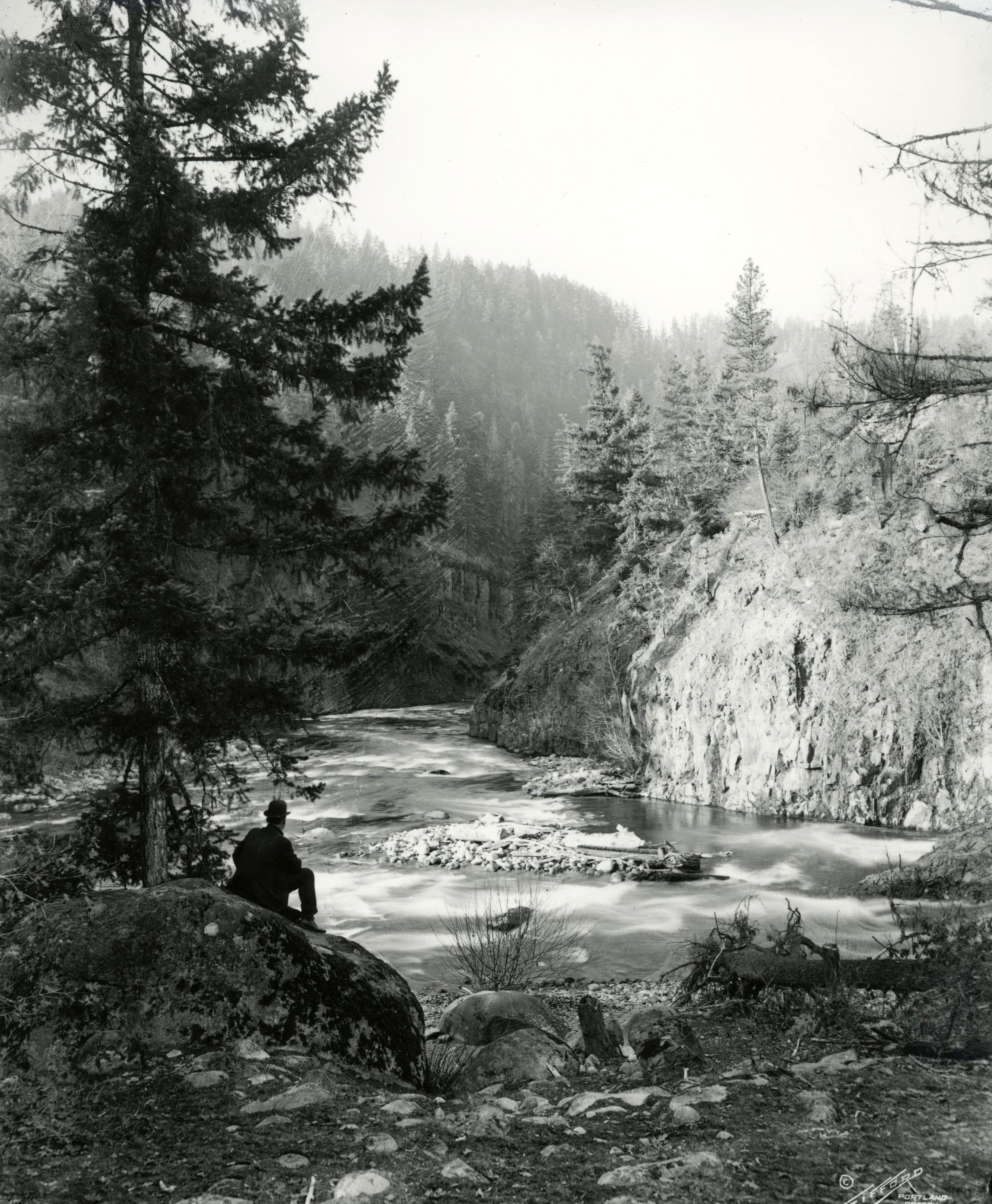

![]()

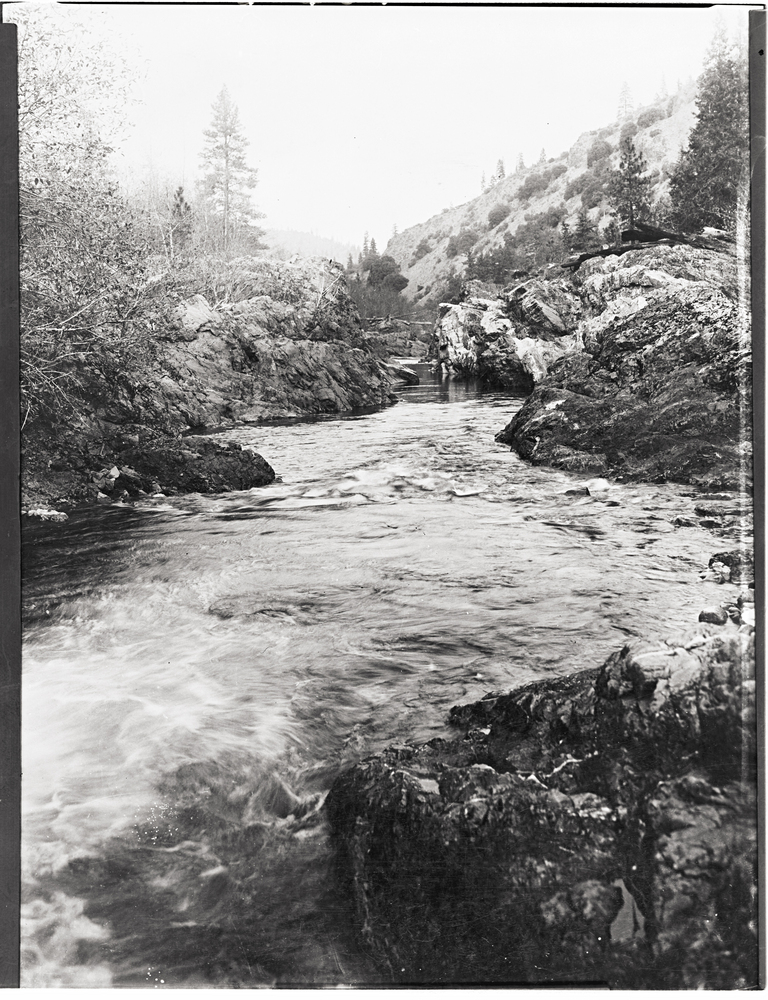

Rogue River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Benjamin Gifford, Org. Lot. 982, Box 3, folder 21, Gi1926

-

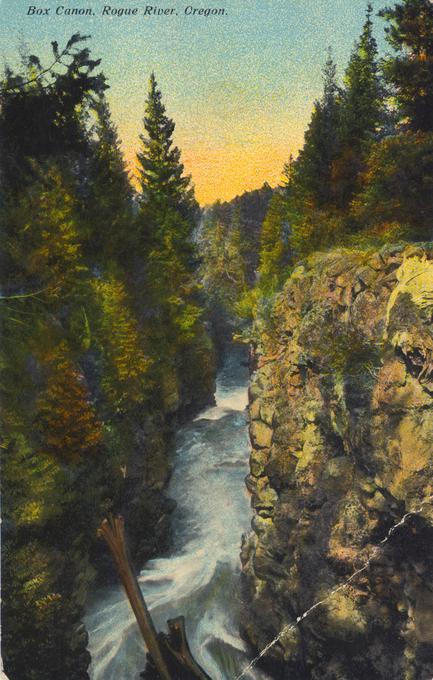

![]()

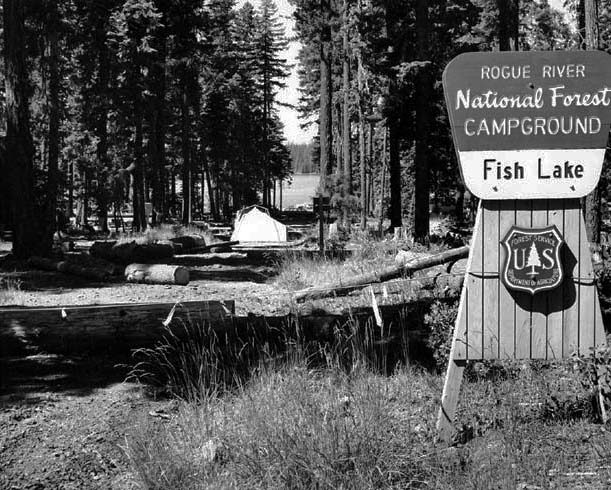

Box Canyon, Rogue River, c.1910.

Courtesy Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Gerald Williams coll.

-

![]()

Rogue River, c.1965.

Courtesy Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Robert Henderson

-

![]()

Rogue River Basin map.

Courtesy Oregon Encyclopedia

-

![]()

Rogue River Basin Project Distribution System Map, 1954.

Courtesy U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

-

![]()

Rogue River Basin Project Map, 1965.

Courtesy U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

Related Entries

-

![Applegate River]()

Applegate River

The approximately sixty-mile-long Applegate River is one of three north…

-

![Bear Creek Valley]()

Bear Creek Valley

Oregon has over ninety separate streams named Bear Creek (far more, in …

-

![City of Gold Hill]()

City of Gold Hill

The city of Gold Hill was founded on gold and the railroad—along with t…

-

![Gold Beach]()

Gold Beach

The City of Gold Beach sits just south of the Rogue River, about forty …

-

![Grants Pass]()

Grants Pass

Located on the Rogue River about thirty miles northwest of Medford, Gra…

-

![Rogue Basin Coordinating Council]()

Rogue Basin Coordinating Council

In 1995, the Oregon legislature passed HB 3441, which provided guidance…

-

![Rogue River Bridge]()

Rogue River Bridge

The Rogue River Bridge spans the mouth of the Rogue River between Gold …

-

![Rogue River National Forest]()

Rogue River National Forest

For over a century, the Rogue River National Forest has filled an impor…

-

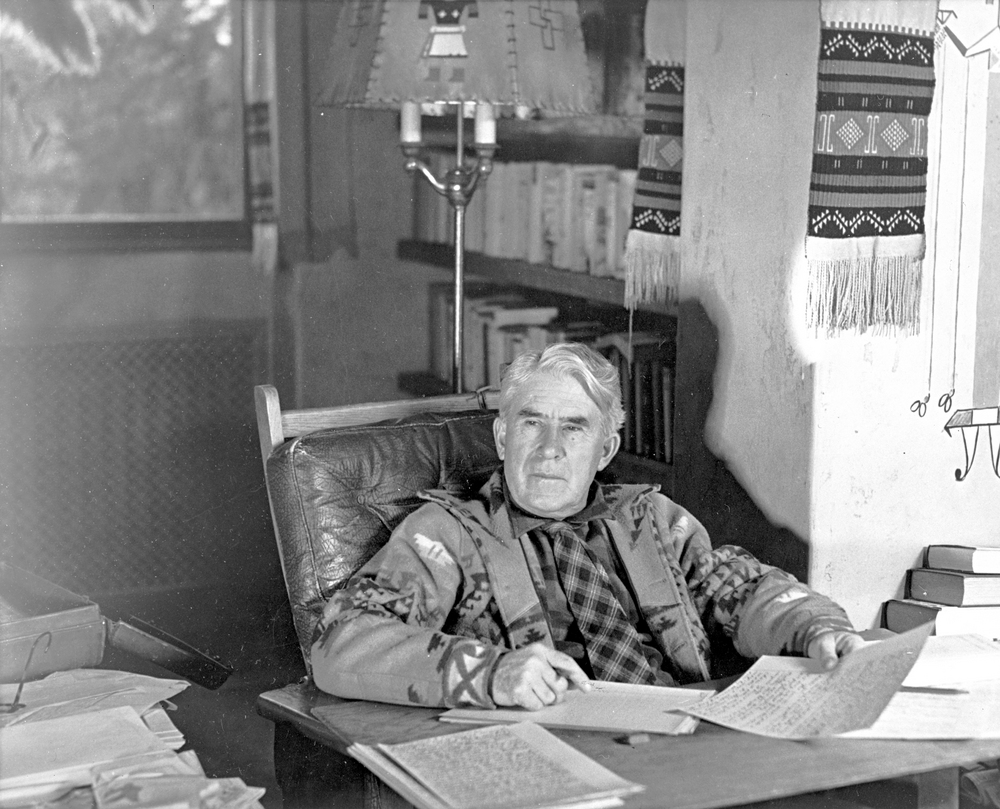

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Siskiyou Pass]()

Siskiyou Pass

Siskiyou Pass, including the 4,310-foot-high Siskiyou Summit of Interst…

-

![Table Rocks]()

Table Rocks

The Table Rocks, two large mesas north of Medford, rise nearly 800 feet…

-

![Zane Grey (1872–1939)]()

Zane Grey (1872–1939)

Inveterate angler Zane Grey, writer of highly popular Western fiction, …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

(Please note that, for sports-fishery purposes, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife uses a somewhat different “upper/middle/lower” segmentation of the river’s course than is used above).

Crown, Julia, Bill Meyers, Heather Tugaw, and Daniel Turner Introduction: Rogue River Basin TDML Study. Salem: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, 2008.

Oregon Department of State Lands. Rogue River Navigability Report, 2008. (Archived document maintained by Oregon State Library at: http//:digital.osl.state.or.us > islandora > object > osl:14109)

Orr, Elizabeth L., and William N. Geology of Oregon (6th ed.). Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2012.