The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855, when self-styled volunteers attacked Native people in the Rogue Valley. It ended in June 1856 with the removal of most of the Natives in southwestern Oregon to the Coast Reservation, which later became the Siletz Reservation. From 235 to 267 Indian people are thought to have been killed in the war, together with fifty soldiers, among them thirty-three volunteers and seventeen regular troops. By one account, Indians killed forty-four white civilians.

Before colonization, an estimated ninety-five hundred Indian people lived in the region where the Rogue River War was fought, including speakers of Takelman and Shastan languages to the east, in the main Rogue Valley of present-day Josephine and Jackson Counties, and speakers of Athapascan languages to the west and along the coast. Fewer than two thousand Indian survivors of the war were counted on the reservation in 1857.

The people of the Rogue Valley had a reputation for violence among non-Indians, although trappers who killed Native people in 1834 were responsible for the first recorded deadly encounters with outsiders. Travel on the trail through the valley to California increased in 1848 due to the Gold Rush, and tensions in the valley increased as well. Jacksonville was established in the Rogue Valley after the discovery of gold on Jackson Creek in late 1851 or early 1852.

Volunteer companies organized in the summer of 1853 after a series of violent exchanges. Two battalions commanded by Joseph Lane, territorial delegate to Congress, pursued Native people into rough country north of the Table Rocks. After volunteers made an assault, Indian leaders asked for negotiations; and Lane and Indian Service superintendent Joel Palmer made treaties on September 8 ("a treaty of peace") and September 10 (for "cession and relinquishment" of land). Native leaders sold roughly two thousand square miles to the Americans and accepted a reservation of about one hundred square miles north of the Rogue River.

Clashes in nearby Northern California in the summer and autumn of 1855 and agitation by rival politicians led to an anti-Indian meeting in Jacksonville on October 7. Most of those present expressed approval of a plan put forward by a newly elected Democratic territorial representative, James A. Lupton, to exterminate Native people living off the reservation. Early the next morning, seven parties of about 115 men set out to attack Indian camps. In those attacks, Lupton and another white man were mortally wounded, and ten more were injured in the initial assault, by one report; forty Indians were killed in the first attack. One witness said half the dead were women and children.

Drought had put miners out of work in the Rogue Valley, and the prospect of being fed and eventually paid for joining volunteer companies may have encouraged men to take part in the initial attacks and subsequent war. In June and July, volunteers in the 1853 campaign together had been paid a little less than $70,200; their suppliers got about $151,400.

Followers of the principal chief on the Table Rock Reservation, Toquahear (which means wealthy), known as Sam by whites, declined to fight. He and his followers were removed under military escort to the Grand Ronde Reservation in the northwest Willamette Valley in February 1856. Immediately after the October 1855 Lupton massacre, many other Native people fled westward down the Rogue River, killing at least eighteen white people in their path. About fifty miles downriver, at the mouth of Galice Creek, they attacked a fortified mining camp that was blocking their way, burning down most of the miners’ shacks and killing four men.

In late October, regular U.S. Army troops coming from the coast found the Indians’ hiding place near Grave Creek and, together with local volunteers, attacked them on the morning of October 31. In what became known as the Battle of Grave Creek Hills or the Battle of Hungry Hill, about four hundred troops are said to have taken part in the attack against from seventy-five to four hundred Natives, including many women and children. The troops charged into a canyon, became disorganized, and were driven back, with between eleven and thirty-five killed and mortally wounded. The troops and volunteers withdrew after Indians attacked their camp the next morning.

On February 22, 1856, a Native force, perhaps of people involved in fighting upriver, overwhelmed a volunteer camp near the mouth of the Rogue River. The town of Ellensburg (present-day Gold Beach) and all of the dwellings between the Rogue River and Port Orford were burned, and survivors fled to an improvised fort north of the river. In March, however, regular troops moving north from Crescent City, California, encountered little resistance.

Bvt. Lt. Col. Robert Buchanan, commander of the regulars, camped at Oak Flat on the Illinois River, near its confluence with the Rogue. On May 20, leaders of the bands involved in the war conferred with him. Although Tecumtum refused to surrender, others promised to surrender their bands at Big Bend, downriver from the Meadows. But on May 27, the commander at Big Bend, Capt. Andrew J. Smith, noted followers of Tecumtum infiltrating and stirring up the people gathering there. In the late morning, they attacked his troops. Fighting continued until Smith was reinforced late the next afternoon. Buchanan reported eleven regulars killed.

Most of the Indian survivors of the war were sent by steamboat from Port Orford to Portland and from there to the Grand Ronde Reservation in June 1856. Tecumtum surrendered in late June, and his followers, along with two bands from the south coast, had to make the journey on foot. Many of those sent north were moved to the mouth of the Salmon River on the coast and subsequently to the Siletz Agency on the Coast Reservation.

-

![]()

A notice by the governor to cease vigilante hostilities against Indians.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

A call to arms against Indians in the Rogue Valley region.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.. Coll 400

-

![Tecumtum was also called Chief John, as he was identified in this photograph, likely from a newspaper story.]()

Tecumtum.

Tecumtum was also called Chief John, as he was identified in this photograph, likely from a newspaper story. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi4355

-

![]()

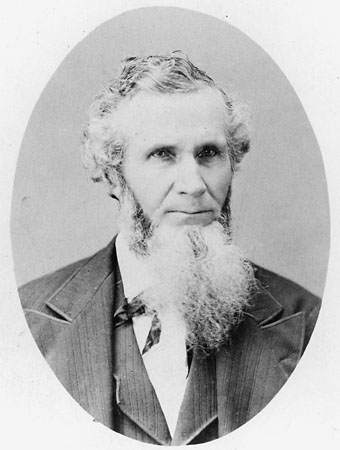

Joel Palmer, c.1860.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi362

-

![General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703]()

General Joseph Lane.

General Joseph Lane, ba018668 OrHi 1703 Credit Oregon Historical Society Research Library

-

![]()

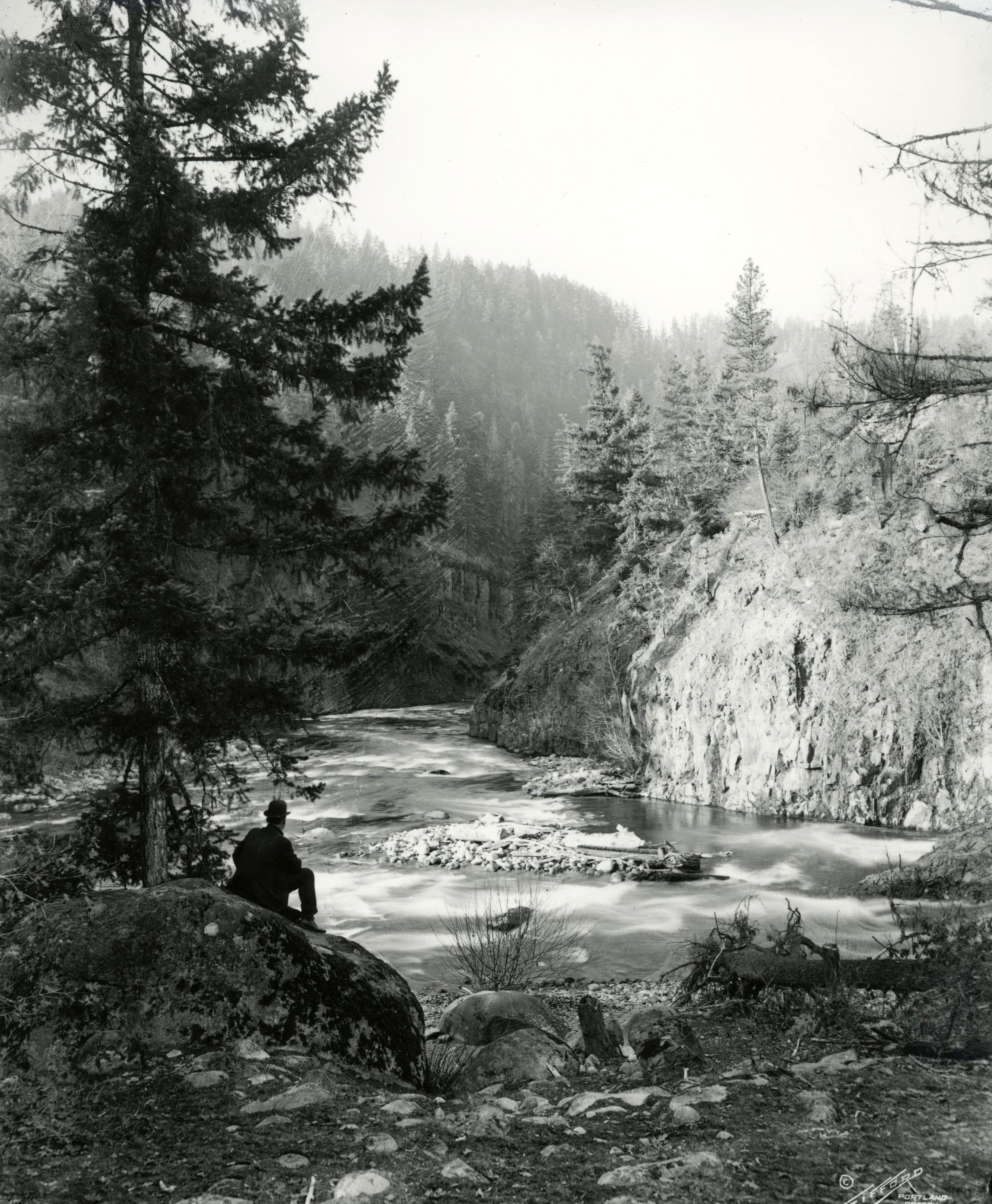

Table Rock, 1887.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 003842

-

![]()

Plaque commemorating the signing of the Rogue Treaty, present-day Camp White, 1942.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 007155

Related Entries

-

![1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry]()

1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry

During the 1860s, the major military-Indian conflicts of the Pacific No…

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1856, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![City of Gold Hill]()

City of Gold Hill

The city of Gold Hill was founded on gold and the railroad—along with t…

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Joseph Lane (1801-1881)]()

Joseph Lane (1801-1881)

Joseph Lane was the first governor of Oregon Territory. A leading Democ…

-

![Rogue River]()

Rogue River

The Rogue River, Oregon’s third-longest river (after the Columbia and W…

-

![Tecumtum (?-1864)]()

Tecumtum (?-1864)

Tecumtum, whose name means Elk Killer, was the principal chief of the E…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beckham, Stephen Dow. Requiem for a People: The Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971. Reprint: Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1996.

Douthit, Nathan. Uncertain Encounters: Indians and Whites at Peace and War in Southern Oregon, 1820s-1860s. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2002.

Schwartz, E.A. The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.