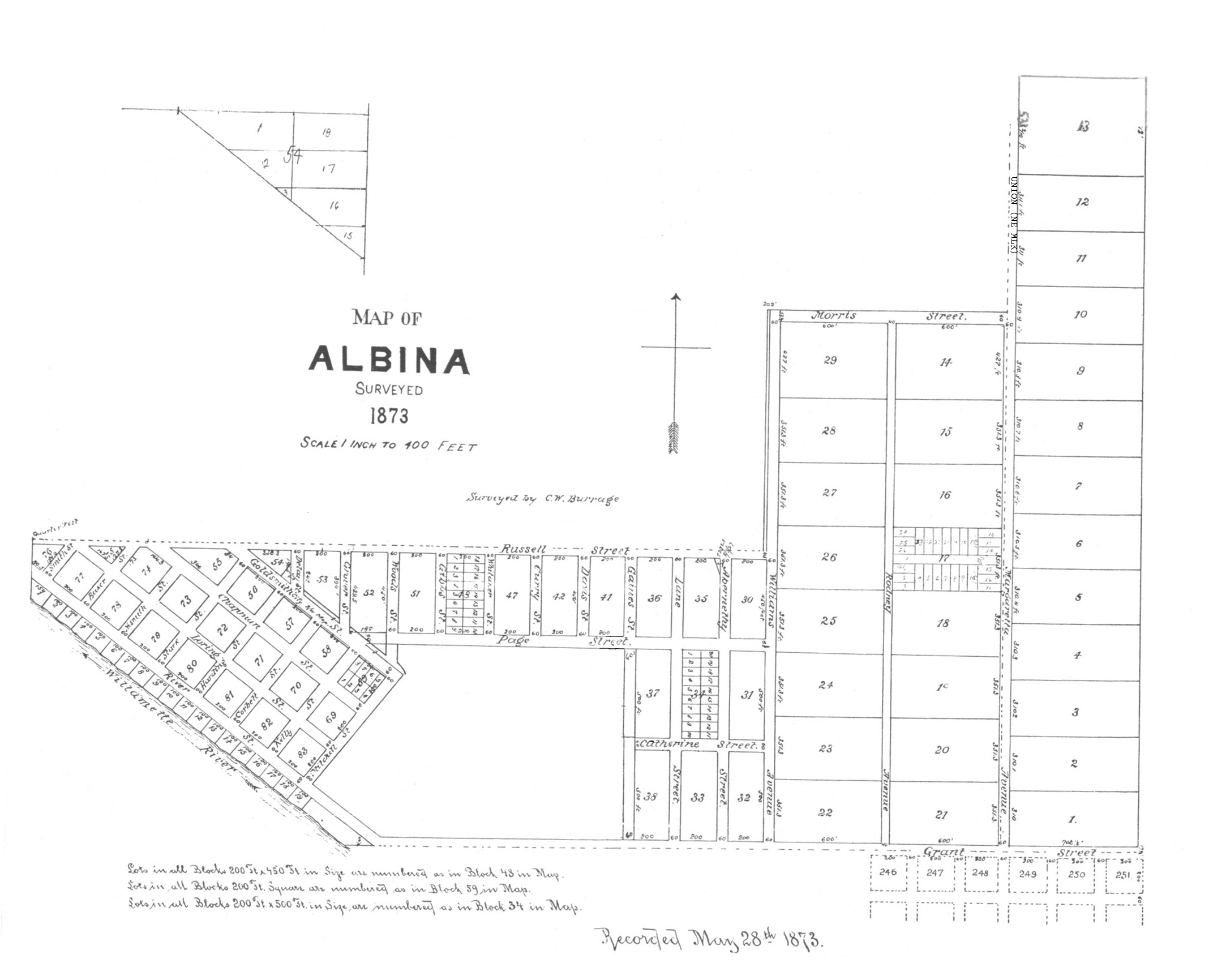

The first group of Volga Germans arrived in Oregon in 1881, encouraged by the economic opportunies offered by Henry Villard's transportation and resources company, the Oregon Improvement Co. About twenty-four households from Kansas traveled on the Union Pacific to San Francisco, where they boarded a Portland-bound steamer. Some households from the Kansas party remained in Oregon, while the majority settled on railroad company land in Eastern Washington in the fall of 1882. A second group of approximately thirty-six households from Nebraska traveled by rail and wagon train to Walla Walla in the summer of 1882. The majority remained in Walla Walla or moved onto land near Ritzville, Washington. A smaller number of households continued their migration to Portland where they settled in the newly platted railroad town of Albina (annexed to Portland in 1891), on the east side of the Willamette River. Many more Volga Germans immigrated to the area between 1890 and 1895, primarily from the colony of Norka, Russia.

The Volga Germans trace their history to the Volga River region in Russia, where they settled as the subjects of an eighteenth-century colonization project designed to modernize Russia and secure its borderlands. The project came to fruition when Catherine the Great issued the Manifesto of 1763 to offer special benefits and a protected colonial status for immigrants who agreed to settle in Russia, particularly in the borderlands of the lower Volga region. The privileges she promised settlers included freedom of religion, the right to retain a traditional language, the provision of free farming land, and permanent exemption from military service for colonists and their descendants. Russian diplomats and recruiters promoted the Manifesto across Europe, and the campaign proved exceptionally successful in the central regions of the Holy Roman Empire’s kingdom, where the devastation of the Seven Years’ War provoked widespread social, political, and economic turmoil. The enlightened offerings described in Catherine’s Manifesto of 1763 lured thirty thousand immigrants to Russia between 1764 and 1767.

The first groups of Volga Germans migrated to the United States in 1875, leaving their Russian homeland when Tsar Alexander II abrogated the freedoms promised by Catherine's Manifesto. The immigrants initially settled primarily in Kansas and Nebraska, where they established farms under the provisions of the 1862 Homestead Act. After several years of drought and grasshopper infestations, many migrated to the Pacific Northwest.

The heavily forested land around Portland was unsuitable for farming, so some of the newcomers moved to the Palouse in eastern Washington Territory. A small number of families settled on farmland near Bethany, Cornelius, and West Union in Washington County, while others moved to Canby, Silverton, and Philomath in the Willamette Valley. The majority remained in Albina and took jobs with the railroads, mills, and factories on the rapidly growing east bank of the Willamette River. They built modest homes in and near Albina and established stores that primarily served their own community, although some businesses, such as Steinfeld's Foods, served a larger market. For decades, local Volga German families—including the Deines, Derr, Glanz, Helzer, Hohnstein, Klaus, Lehl, Miller, Schleining, Schnell, Schwartz, Spady, Traudt, and Wacker families—owned ninety percent of the garbage collection businesses in Portland. Records typically classified them as Russian immigrants who spoke German, and some Portlanders referred to the Albina settlement as "Rooshian Town" or "Little Russia." But their first language was German, and they identified as Germans from Russia or as Volga Germans.

Volga German immigrants attended and helped build several churches in the area, some of which still stand. Established in 1882, the St. Peter's Lutheran Church in Blooming (near Cornelius) is the first known church in the greater Portland area with Volga German members, primarily from a group that arrived from Kansas in 1881. It has been rebuilt three times, most recently in 1989. Although Volga Germans traditionally belonged to a variety of denominations, many joined the German Congregational Church after settling in the United States. The Ebenezer German Congregational Church, built in 1892 at Northeast Seventh Avenue and Northeast Stanton Street, became the mother church of several Volga German Congregational churches. It was replaced by a larger structure in 1904 and sold to the Northeast Community Fellowship Foursquare Church in 1994. Several early settlers in Albina, who had been converts of the Seventh-day Adventist church while living in Nebraska, established the Albina Seventh-day Adventist German Reformed Church in 1889, formerly at North Vancouver Avenue and Northeast Failing Street. Catholic Volga Germans typically attended the Immaculate Heart of Mary Catholic Church on Northeast Williams Avenue. Other churches established by the Volga Germans include the Free Evangelical Brethren Church (1904), St. Paul’s Evangelical and Reformed Church (1904), the Second German Congregational Church (1913), and the Zion German Congregational Church (1914). All but the St. Paul’s church building remain standing.

A second wave of Volga Germans emigrated directly from Russia to the Portland area in the early decades of the twentieth century. By 1920, about 7,000 German Russians lived in Oregon, a large percentage of them in Portland. World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the Russia Civil War impeded communication between Volga Germans in Russia and those in the United States, bringing immigration to a halt. Anti-German feelings increased in the U.S. during this period, but the Volga Germans bore no ties to the German Empire, which did not emerge as a nation until 1871. Volga Germans also did not identify culturally or ethnically as Russians. During the war, they asserted their American identity by serving in the U.S. military, buying Liberty Bonds, and proudly displaying American flags at their homes.

By 1920, more than five hundred Volga German families in Oregon lived in the ethnic enclave bound roughly by Northeast Alberta Street to the north, Northeast Fifteenth Avenue to the east, Northeast Knott and Northeast Russell Streets in the south, and North Mississippi and North Albina Avenues to the west. When a famine struck the lower Volga region in Russia in the early 1920s, George Repp and George W. Miller turned to the community to help form the Volga Relief Society. The organization worked with Herbert Hoover's American Relief Administration (ARA) to send food and clothing to the stricken area. Repp, who had immigrated to Portland from Russia, left his grocery and meat market business on Union Avenue and traveled to Russia to direct relief efforts in the Volga German colonies. The collaborative effort saved thousands of lives. Many Volga German men and women also served in the armed forces and worked in local shipyards and factories during World War II.

The forces of assimilation common to many immigrant groups broke down the old order in the Volga German community during the postwar period, as members of the younger generation no longer wished to use German as their primary language and many married outside the community. Community members continue to engage their history through cultural programs held by the Oregon Chapter of the American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, established in 1971.

-

![]()

Portrait of Johannes Jörg, one of the early Volga Germans to settle in Albina, Oregon..

Courtesy of Ruth Ann Plue

-

![]()

Wedding portrait of a Volga German couple in the Albina district, early 1900s..

Courtesy Stacy Hahn

-

![]()

The congregation of the German Evangelical Congregational Brethren Church, NE Mason and Garfield Ave., Portland, c1927.

Courtesy Steven Schreiber

-

![]()

Zion German Congregational Church, on NE 9th and Fremont, taken from Irving Park, Portland..

Courtesy of Marie Trupp Krieger

-

![]()

Immaculate Heart Church, Portland.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., PAM 282.79111.133comm1963

Related Entries

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

The Volga Germans. https://www.volgagermans.org

Haynes, Emma Schwabenland. Emma's Thesis: The German-Russians on the Volga and in the United States. Lincoln, Neb.: AHSGR, 1996.

Pleve, Igor R. The German Colonies on the Volga: The Second Half of the Eighteenth Century. Trans. Richard R. Rye. Lincoln, Neb.: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, 2001.

Sallet, Richard. Russian-German Settlements in the United States. Fargo: North Dakota Institute for Regional Studies, 1974.

Schreiber, Steve. Norka, Russia. Last modified August 6, 2020. https://www.norkarussia.info/

Schreiber, Steve. The Volga Germans in Portland. Last modified August 6, 2020. https://www.volgagermansportland.info/

Scheuerman, Richard D., and Clifford E. Trafzer. Hardship to Homeland Pacific Northwest Volga Germans. Pullman, Washington: Washington State University Press, 2018

Viets, Heather. “Little Russia: Patterns in Migration, Settlement, and the Articulation of Ethnic Identity Among Portland’s Volga Germans.” MA thesis, Portland State University, 2018.