Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazement at how white the population of Oregon and the City of Portland is compared to other parts of the country. It is not possible to argue with the figures—in 2017, there were an estimated 91,000 Black people in Oregon, about 2 percent of the population—but it is a profound mistake to think that these stories and statistics tell the story of the state's racial past. In fact, issues of race and the status and circumstances of Black life in Oregon are central to understanding the history of the state, and perhaps its future as well.

Early Contact and Settlement

The first well-documented Black person in Oregon is Markus Lopius, a crewmember of the American ship Lady Washington, captained by Robert Gray in 1788. He was added to the crew when the ship stopped at the Cape Verde Islands in the Atlantic, off the Africa coast. Lopius, described as a young Black man, was hired as Gray's "servant," but he also performed the same jobs and duties as other crew members. At Tillamook Bay on the present-day Oregon Coast, Lopius was on shore cutting grass for the ship's stock when a local Native ran off with his cutlass. Lopius caught the thief, upon which other Indians attacked him with knives and spears. He was finally felled by a flight of arrows as he tried to reach his fellow crew members.

Even more information is available about York, the next documented Black person to arrive in Oregon. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled down the Columbia River on the last leg of its journey to the Pacific Ocean. York, William Clark’s slave, was a member of the expedition. He played a significant role in the success of the enterprise, transporting supplies, hunting for food, participating in scouting and side trips, and constructing forts and shelters. He was also the first Black person that some of the Natives they encountered had ever seen, making him an important diplomatic asset in establishing relationships with resident populations. When the expedition was near starvation on the return trip in 1806, York was able to secure needed provisions as an emissary to people who lived along the way.

In the years that followed, the development of the fur trade in the Pacific Northwest attracted a group known as mountain men, who worked with local Natives to supply beaver and other furs to the Hudson’s Bay Company and other companies. Traders such as Jedediah Smith used Black slave labor in their work; and some free Black mountain men, such as Moses “Black” Harris, became legendary figures in the fur trade and later worked as sought-after wagon train guides.

James Douglas, known as "Black Douglas," served with distinction as chief factor at Fort Vancouver in the 1840s. Douglas was born in Demerara, British Guiana, in 1803. His father, John Douglas, was a Scottish merchant who managed a family sugar plantation, and his mother, Martha Ann Ritchie, was a free "coloured" woman from Barbados. Douglas’s parents never married, but his father took him to Glasgow in 1812. In 1819, James Douglas entered the North American fur trade as an indentured worker with the North West Company. After many years of working for the Hudson's Bay Company, he reached the pinnacle of his power in the 1850s and 1860s when he served concurrently as the second governor of Vancouver Island and the first governor of British Columbia. For his service, Douglas was knighted by Queen Victoria.

Exclusion Laws

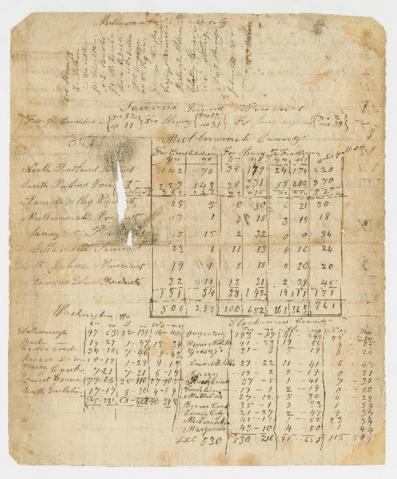

During the wagon train era, from 1840 to 1860, Black participation in overland trail migration was kept small by both national and local public policy. Nationally, over three million Black people in the American South were restrained by their status as slaves held by white owners. The provisional and territorial governments in Oregon banned slavery, but some settlers were determined to create a white homeland by making Black residence of any kind illegal. To do so, it was necessary to exclude both slave and free Black people.

The first Black exclusion law in Oregon, adopted in 1844 by the Provisional Government, mandated that Black people attempting to settle in Oregon would be publicly whipped—thirty-nine lashes, repeated every six months—until they departed. There is no documented record of any official whipping—the law was written with a grace period, and it was repealed before it had expired—but the concept was clear. In 1849, the Oregon Territorial Government adopted a second Black exclusion law, which was repealed in 1853.

The Oregon constitution, adopted in 1857, banned slavery but also excluded Black people from legal residence. It made it illegal for Black people to be in Oregon or to own real estate, make contracts, vote, or use the legal system. Like earlier exclusion laws, the constitutional ban, which took effect when Oregon became a state in 1859, was not retroactive, which meant that it did not apply to Black people who were legally in Oregon before the ban was adopted.

There were several periods between 1840 and 1860 when Black people could establish legal residence in Oregon: (1) for about four years, before the adoption of the 1844 ban; (2) for about four years, after the repeal of the 1844 law and before the adoption of the 1849 law; and (3) for about six years, after the repeal of the 1849 law and before the constitutional ban of 1859. During those twenty years, therefore, there were more years when it was legal for Black people to reside in Oregon than when it was illegal. Nevertheless, Oregonians made it clear that Black people were not welcome, and few established residence in Oregon during this time.

The greatest impact of the exclusion laws was not in how many Black people were whipped, sent out of the state, or stopped at the state line but in their deterrent effect on potential Black immigrants. The laws made it clear that Oregon was a hostile destination for Blacks contemplating a move west, and they proved to be remarkably effective. Potential Black immigrants who had the means and the motivation to go west simply chose to go elsewhere. The other factor that complicated issues of Black residence and slavery was the Dred Scott v. Sanford Supreme Court decision in 1857, which declared that slave masters had the right to take their slaves anywhere in the country. That ruling compromised all laws about race and slavery in Oregon at the time.

The Donation Land Act of 1850

The exclusion laws notwithstanding, by far the most devastating anti-Black law passed during this era was the federal Donation Land Act of 1850, which declared that land would only be granted to "every white settler...American half breed Indians included"; the second group was included to make eligible the offspring of early white male settlers and their Indian wives.

By removing most Indians to reservations and excluding all but white landownership, the vision of a white homeland in Oregon was embedded in public policy. In subsequent generations, the profits, power, and political influence that flowed from near exclusive white landownership were manifested in the construction of a racially stratified society in which white ascendancy was assured and nonwhite marginalization was profound. To understand later patterns of political, economic, and social inequality in Oregon, it is necessary to be aware of these early examples of race-based public policy that benefited only the state's white population.

The Civil War Years and Beyond

During the Civil War (1861-1865), the Oregon legislature approved additional anti-Black prohibitions, including a Black poll tax in 1862. The state also prohibited whites from marrying not only Black people but also Chinese, South Pacific Islanders, and any person with more than half Indian parentage. The law, on the books until the 1950s, also punished the person who performed any such marriage ceremonies with a fine and prison. Like the exclusion and land laws, the most powerful effect of such laws was the message they sent that Oregon was a place where only whites were welcome.

In spite of this hostile environment, a small number of Black people immigrated to the Oregon Country, where they made significant contributions. George Bush, for example, crossed the trail from Missouri in 1844 and established a successful frontier farm at present-day Tumwater, Washington. One of his sons would serve in the Washington territorial legislature before the turn of the twentieth century. George Washington, a person of mixed race, crossed the trail with his adopted white family in the early 1850s and established a homestead in western Washington, where he founded the town of Centralia in the 1870s. Significantly, both men settled north of the Columbia River in the part of the Oregon Country that had been under the control of the Hudson's Bay Company, where the influence of American racial policies was less pervasive.

In general, the hostile racial climate continued to retard the immigration of a significant Black population to Oregon between the Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century, and the status and security of those already in the state remained questionable. Black people found it difficult to accumulate wealth and property, and it was virtually impossible for them to acquire political power and influence. Black people who did settle in Oregon lived throughout the state, although in different concentrations and circumstances.

While the percentage of Black people as a part of Oregon's total population was consistently small—less than one percent until as late as 1960—in absolute numbers, there were scores of Black people in Oregon during the trail period, hundreds during the post Civil War era, and thousands during the twentieth century. In the early years, Black people settled wherever whites did in Oregon, experiencing both harsh failures and impressive successes. Generally, their status depended on how they had arrived, who they were associated with, and how well they interacted with their neighbors in a frontier environment.

Changing Labor Opportunities and Restrictions

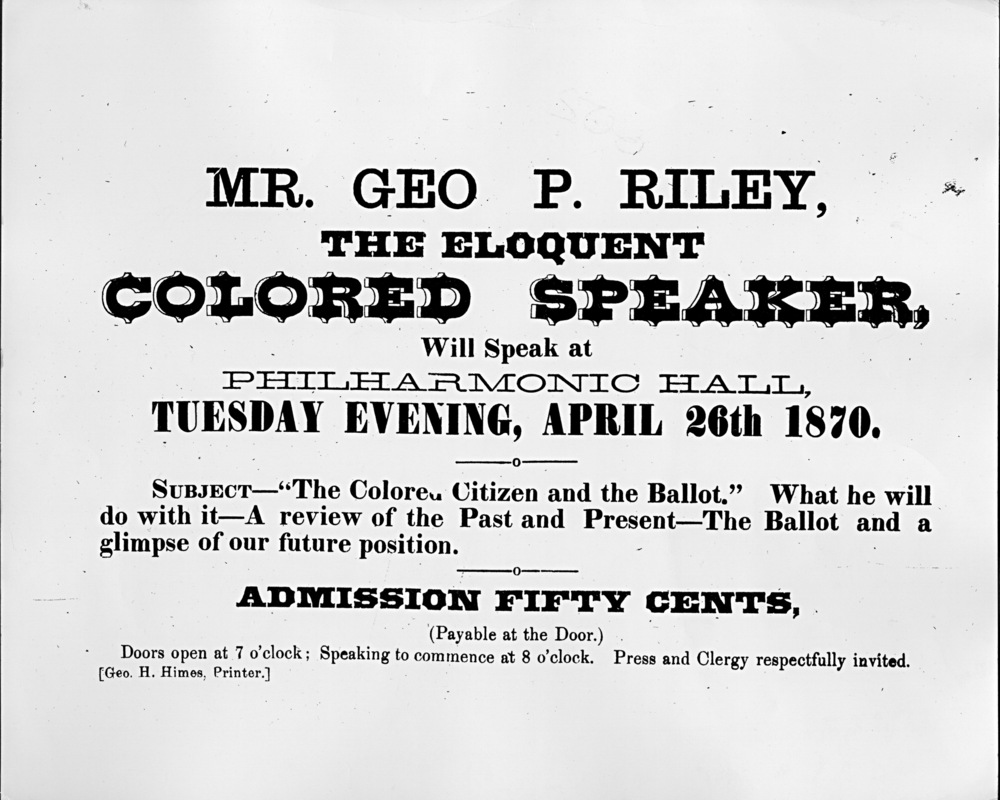

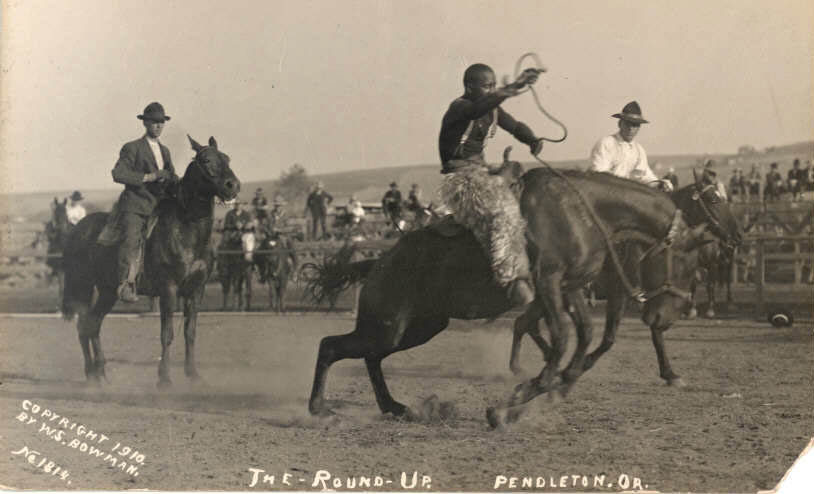

Wherever a demand for specialized labor materialized, Black workers might be recruited elsewhere, imported to Oregon, and then often deported, by formal or informal means, after the need for their labor was exhausted. In the 1890s, for example, when coal deposits were found in the hills around Marshfield (present-day Coos Bay), hundreds of Black people from Appalachia were brought to work in the mines. When the coal was gone, they were encouraged to leave. A few Black cowboys worked the ranches in the Pendleton area and became prominent in the rodeo culture in eastern Oregon during the 1910s. In northeastern Oregon, in the 1920s and 1930s, Black loggers worked the forest around Maxville until the yields were no longer profitable. After the arrival of the railroad in eastern Oregon, some Black families lived in small towns, such as La Grande, providing related services for the railroads.

Wartime and military activities often resulted in the creation of small Black colonies in unexpected places. The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, an all-Black unit known as the Triple Nickles, was stationed in Pendleton during World War II, and the U.S. Air Force base in Klamath Falls later attracted a small Black population. After the 1950s, every city or town in Oregon with a university or college had Black residents, often athletes but also scholars and students. In most of these situations, Black people were expected to accept a subordinate place in Oregon life, forced by circumstances to accept an inferior status, but they did not discard the vision that things would be better for their children.

These relatively small groups of specialized Black labor, however, are not the main story of Black settlement and residence in Oregon. During the late nineteenth century, most Black Oregonians, effectively excluded from rural Oregon by land laws and racial hostility, gravitated to urban centers. Most went to Portland, where they worked for the railroads and related industries. Transcontinental rail service had reached Portland in the 1880s, and the Portland Hotel was built to service the growing business and travel-related needs of the city. While administrative, management, and most supervisory jobs were held by whites, Black people staffed the visible and profitable restaurant and entertainment facilities and provided manual, domestic, and other types of labor. Employment in these two growing industries created the first recognizable Black neighborhood in Portland in what is now Old Town Chinatown and the Pearl District. Work on the railroad and in service—both commercial and domestic—became the economic pillars of Black community life.

Discrimination in the Early Twentieth Century

There was another, less savory economic component to Black Oregon life. When an entire population is prevented by law and social practice from achieving legitimate success through respectable labor and commerce, some members of that population turn to illegitimate activities. Portland was a wide-open town, where police and political corruption thrived well into the twentieth century. Consequently, the city’s underworld of illicit entertainment and “forbidden pleasures”—including bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution—emerged as the most racially fluid and integrated aspect of Portland life. There were legitimate businesses as well, of course, many of them in the Williams Avenue, Vancouver Avenue, Broadway corridor, which became a popular entertainment center of Portland. Black-owned clubs, restaurants, and small businesses flourished in the neighborhood, protected by a well-lubricated system of bribes and kickbacks to local police and political powerbrokers.

Oregon had formalized the practice of racial discrimination early in the twentieth century. In 1904, Oliver Taylor sued a theater owner for refusing him a box seat because of his race; the trial judge dismissed the suit. Lawyer McCants Stewart won the case in appeal (Taylor v. Cohn) in the Oregon Supreme Court in 1906. A subsequent discrimination case argued by McCants in 1917, Allen v. People's Amusement Park, was identical in circumstances to Taylor v. Cohn, but lost in the Oregon Supreme Court, confirming and sanctioning the practice of racial segregation in public places and services—a ruling that would remain in place until the legislature passed an anti-discrimination law in 1953. Segregation was most widely and powerfully practiced in the real estate industry. Restrictive covenants, redlining, and prohibitions in the real estate handbook established the inner northeast section of the city for Blacks. Outside Portland, many rural towns with small or nonexistent Black populations enforced Sundown Laws that required Black people to be out of town by nightfall or face hostile action by the police, private citizens, or both.

By the 1920s, Oregon had a well-established and well-earned reputation as a hostile and dangerous place for Black people. That reputation was solidified by the presence in the state of the largest Ku Klux Klan chapter west of the Mississippi River. The power of the Klan was based on the political influence of its leaders, the potential for economic coercion of whites who did not support Klan ideology, and the awareness that the Klan would not hesitate to use violence to enforce its dictates. During the 1920s, the primary targets of the KKK in Oregon were Catholics and Jews, not Black people. The decades of exclusionary practices had been so successful in keeping the Black population small and isolated that Black people were a secondary target. Still, the Klan was a visible and intimidating force in Oregon politics and society, and it was not uncommon for KKK members to parade through city streets in full regalia—displays that were often followed by torchlight rallies and public cross burnings. Walter Pierce was elected governor in 1923 with KKK support; from 1932 to 1942, he was Oregon’s congressman in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Oregon Black people resisted Klan activities and influence on multiple levels. One of the first NAACP chapter swest of the Mississippi River was organized in Portland in 1914, and it fought KKK propaganda through educational campaigns and protests. When Black people were denied access to white services and goods, individuals in the Black community filled the gap. Black people owned hotels, restaurants, and other small businesses; and fraternal and social organizations and clubs provided both community and recreation. A Black weekly newspaper, the Advocate, owned and edited by activist Beatrice Morrow Cannady, provided communication and inspiration, and Black churches were places to associate, bond, and maintain spiritual and psychological strength.

The years of the Great Depression were a severe challenge to Portland’s Black community, bringing higher unemployment as jobs formerly considered inappropriate for whites were sought after by whites desperate for work. Many Black businesses, chronically underfunded, failed, further fracturing the economic stability of the Black community. Surviving the Depression required all the ingenuity and strength people could muster.

World War II and Changing Demographics

Between the beginning of the twentieth century and World War II, there was a gradual change in the size and location of the Black community in Portland. In the early years, Blacks lived in outlying areas; but as the railroad industry boomed, they gravitated to the neighborhood around Union Station and Old Town. As the size of the community grew, it jumped the Willamette River to the inner northeast area, on Broadway, Williams Avenue, and Vancouver Avenue. By 1940, Oregon’s principal Black community lived in Portland—small, geographically isolated, and artificially confined by the practices of the city’s white power structure. Yet, it was also a cohesive, viable entity that provided what was needed for a fully functional community.

World War II changed the realities of race in Oregon and brought on the beginning of the modern Black experience in the state. Change was both dramatic and swift, as Portland became the center of a wartime shipbuilding industry. Portland’s Black population exploded from about 2,000 in 1940 to a high of 22,000 in 1944, as Black shipyard workers, many of them with families, were recruited from other parts of the country and moved to Portland. A temporary federal housing project, the largest in the country, was built on the Columbia River to house wartime workers. About a quarter of the residents of the new city, named Vanport for its location between Portland and Vancouver, were Black. The major racial issue during this period involved the largest shipyard union, the Boilermakers, which prohibited Black membership, with the complicity of shipyard management. As a result, Black workers had the least skilled jobs in the yard, which made them more vulnerable than whites to layoffs and unemployment.

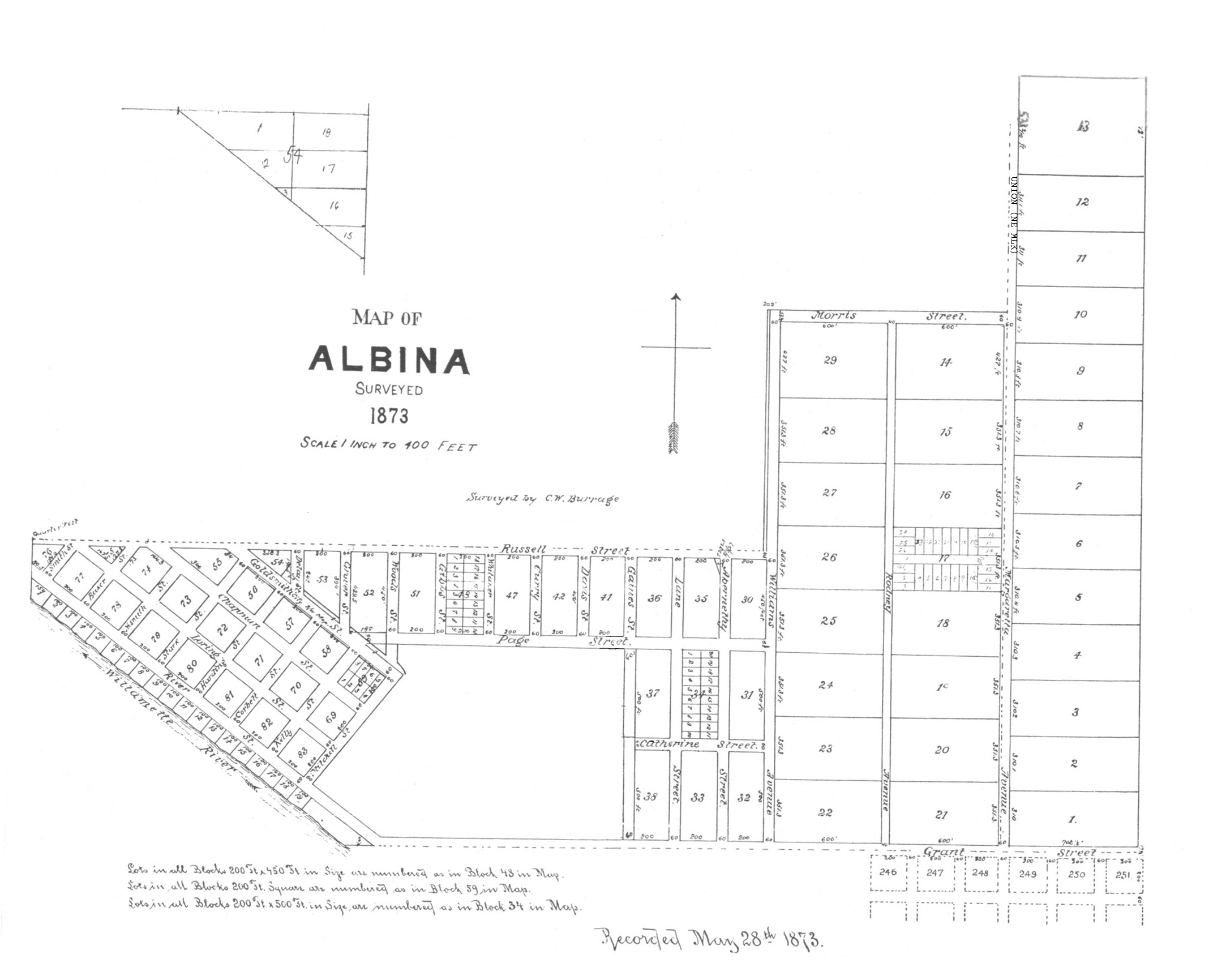

At the end of the war, many Black people left the state as shipyard jobs disappeared, but many decided to stay. The postwar Black population stabilized at about six times the size of the prewar population. Most lived in Vanport, until a devastating flood on the Columbia in 1948 swept that city away. Finding a place for displaced Black residents from Vanport to live became a racial crisis. The inner northeast area of Portland, known as the Albina District, was identified by the city’s financial and political power structure as a target area for Black resettlement. The neighborhood was favored because of its older, less desirable housing and its proximity to both Vanport and the older Black community. Further, more and more whites were leaving the city for the suburbs, and creating a Black neighborhood in Albina did not interfere with or threaten that exodus.

The circumstances of these demographic changes pushed Portland in new directions in racial matters as Oregon entered the 1950s. The war against racism overseas during World War II had revealed some unpleasant racial practices and realities in the United States. The most blatant example was the internment of innocent Japanese American citizens in concentration camps without due process. Some German and Italian nationals and citizens were incarcerated, but in much smaller numbers than the Japanese. The war years had also focused attention on the long-standing issues of racism directed at Black Americans.

After the war, most Black people in the South were still prevented from voting, holding public office, getting a quality education, and having access to financial and economic success. Black people in the South could not even be said to have a right to life under Southern racial traditions. This system of white supremacy was maintained by the willingness of racist police and terrorist organizations like the KKK to use racial violence to protect the status quo. In the North and the West, Black people were not generally in as much danger, but they did suffer from systematic repression. Employment discrimination, racial quota systems in higher education, de facto segregation in schools, discrimination in banking and financial services, real estate prohibitions, police brutality, and policies that forced most Black people to live in segregated circumstances were all routinely a part of Black life in the West. Popular culture projected negative racial stereotypes on Black people, and then used the stereotypes to justify discriminatory treatment.

After World War II, however, racial and civic reform movements began to gain energy and support from a growing number of whites. In Oregon, this activist element combined with persistent historic efforts by Black people to achieve a series of progressive advances and victories—a fair employment law (1949), a public accommodations law (1953), and a fair housing law (1957). Although the new laws did not automatically change prevailing racist practices, they did represent a counterpoint to Oregon’s and the nation’s anti-Black traditions.

Schools, Community-Police Relations, and Activism

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. By the 1960s, Portland and many other communities in the country were struggling with how to integrate schools in a segregated city—a legacy of the housing restrictions placed on Black people in the past. The NAACP pushed hard for the integration of Portland schools, but stiff resistance from the city’s educational and political elites, including the school board and conservative-leaning politicians and residents, led to the Blanchard Plan, named after the superintendent of Portland schools, Robert Blanchard. The plan, to be implemented in 1970, called for busing Black students to white schools and systematically closing schools in Black neighborhoods. By the mid-1970s, the school board had voted to close Jefferson High School, which served most of the city’s Black community.

Under the Blanchard Plan, a grade level in schools in Black neighborhoods were to be closed each year—that is, eighth grade one year, seventh grade the next, and so on. Black students in that grade would have no option but to attend a white school. In 1979, for example, the 450 Black students who could no longer attend King Elementary School were scheduled to be sent to forty-two different schools in outlying white neighborhoods. The capstone of the Blanchard Plan was to be the closure of Jefferson High School, and many Blacks at the time considered both Blanchard and Newman to be educational villains for their dogged determination to close the schools in Black neighborhoods. In 1979, school board chairman Jonathan Newman resigned when a longtime critic of the Blanchard Plan was appointed to the board. In 1980, Blanchard was fired in an acrimonious end to his eleven-year tenure as superintendent. Jefferson High School remained open.

Much of the turmoil had been caused by the board's refusal to embrace the findings and recommendations of the Community Coalition for School Integration, a broad-based collection of twenty-eight organizations that opposed closing Jefferson High School. After the board disbanded in frustration, the Black United Front emerged as the principal opponent of the school board. Firmly based in the Black community and under the leadership of co-chairs Rev. John Jackson and Ron Herndon, the Front challenged the board with an aggressive array of tactics, which included heated rhetoric, boardroom invasions, community rallies, street protests, and threatened school boycotts.

Eventually, Front-advocated approaches became a battlefield in the so-called culture wars that raged as the neoconservative movement became more powerful in the nation. New approaches and new strategies would be tried over the coming decades, but problems like the achievement gap between Black and white students, uneven application of discipline to students of color, and graduation rates continue to be unsolved in the twenty-first century.

The other major racial issue in Oregon during this period involved the relationship between the Black community and the police, as many Black people charged the police with brutality and racism. In the summers of 1967 and 1969, race riots exploded along Northeast Union Avenue, the main thoroughfare of the Black community at the time. Police and their supporters attributed the riots to "outside agitators" and lawless militants. Many Black people laid the blame on police incitement and the harassment of Black youth.

Beginning in the 1970s and through the 1980s, several high-profile police shootings of young Black men in Portland and questionable police practices created intense animosity toward the police. In 1981, two policemen admitted that they had placed four dead possums in front of the Burger Barn, a popular Black-owned, late-night hangout at 3962 Northeast Union Avenue. The incident escalated into a major confrontation and had a long-term effect on police community relations. The person in charge of the Portland Police Bureau was Black commissioner Charles Jordan, who received a vote of no confidence from the police union. Mayor Frank Ivancie fired the chief of police and removed the bureau from Jordan’s portfolio, bringing it under his own supervision.

On November 2, 1982, the voters approved Ballot Measure 51, which established the first public police review committee in Portland. The committee of nine citizen volunteers appointed by the city council and three city council commissioners would review the results of all internal affairs cases in the bureau and make recommendations. One such case occurred in 1985, when Lloyd Stevenson, a Black man, was killed by a policeman using a choke hold. Neither of the two officers involved was disciplined. The case took a bizarre and controversial turn when on the day of Stevenson's funeral, two police officers sold t-shirts to fellow officers bearing the slogan “Don't Choke 'Em, Smoke 'Em.” They were fired but were eventually reinstated with back pay.

By the last decades of the twentieth century, two other racial developments helped define Black-white relations in Portland. In the late 1980s, a violent skinhead movement identified Oregon, particularly Portland, as one of several locations in the Pacific Northwest suitable for white homeland, and Portland became a very real danger zone for Black people. After the murder of Ethiopian exchange student Mulugeta Seraw in November 1988, Kenneth Mieske, a member of East Side White Pride, was convicted for the crime. Tom and John Metzger, neo-Nazis from California and founders of White Aryan Resistance (WAR), were convicted in a civil trial for encouraging Mieske and others to commit violence against Black people.

The second development, one with more lasting consequences, had begun years earlier in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the construction of Memorial Coliseum and Interstate 5 removed much of the Black community on the Northeast Broadway, Williams Avenue, Vancouver Avenue corridor. In the 1970s, the expansion of Emmanuel Hospital did the same to Black residents in the Williams Avenue, Vancouver Avenue, and Russell Street neighborhood. While the destruction had created hardships and generated hostility and suspicion toward white decision makers, there remained the belief that Portland would continue to have a geographically identifiable Black community.

That belief came under fire in the 1990s, when real estate developers and a resurgent interest in an urban lifestyle ushered in an era of gentrification that transformed traditional Black neighborhoods and forced many Black people into low-income housing in suburbs like Gresham and Beaverton. Many Black people were left to wonder if the threat of a white homeland had finally been realized in northeast Portland. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Portland and Oregon continue to have a significant Black population that will be represented in whatever future lies ahead for the state.

-

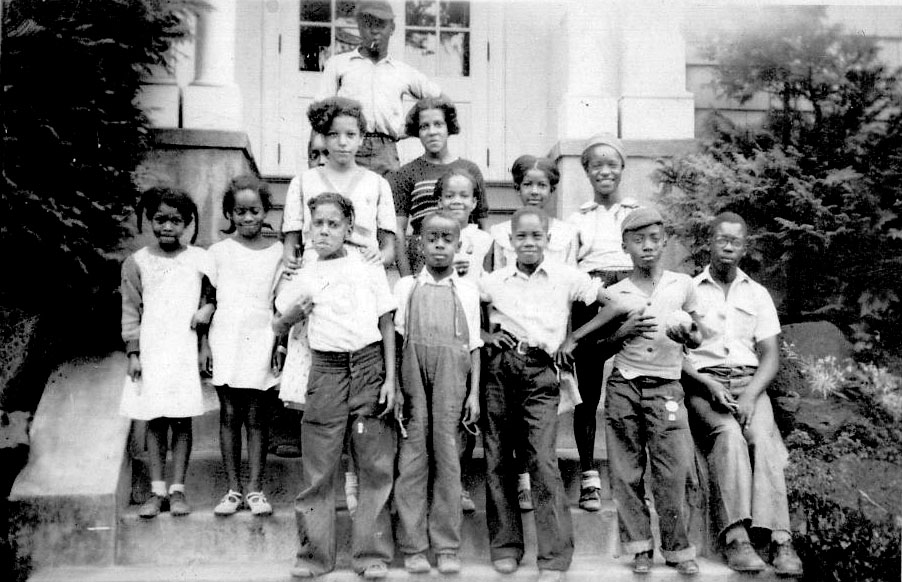

![YWCA children's band in Portland. Photo by Elizabeth Hall.]()

YWCA children's band.

YWCA children's band in Portland. Photo by Elizabeth Hall. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![Sybil Harber, midwife in Lakeview, Oregon.]()

Sybil Harber, c. 1900.

Sybil Harber, midwife in Lakeview, Oregon. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 10690

-

![Officer George Hardin, first black police officer in Portland, 1894-1915.]()

Officer George Hardin.

Officer George Hardin, first black police officer in Portland, 1894-1915. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi81769

-

![Unidentified woman living in Oregon, c. 1890]()

Unidentified woman living in Oregon, c. 1890.

Unidentified woman living in Oregon, c. 1890 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi94390

-

![Matilda Booth Thatcher, matriarch of the Thatcher-Flowers family, Portland. Her family owned land around Mt. Scott.]()

Matilda Booth Thatcher.

Matilda Booth Thatcher, matriarch of the Thatcher-Flowers family, Portland. Her family owned land around Mt. Scott. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi25140

-

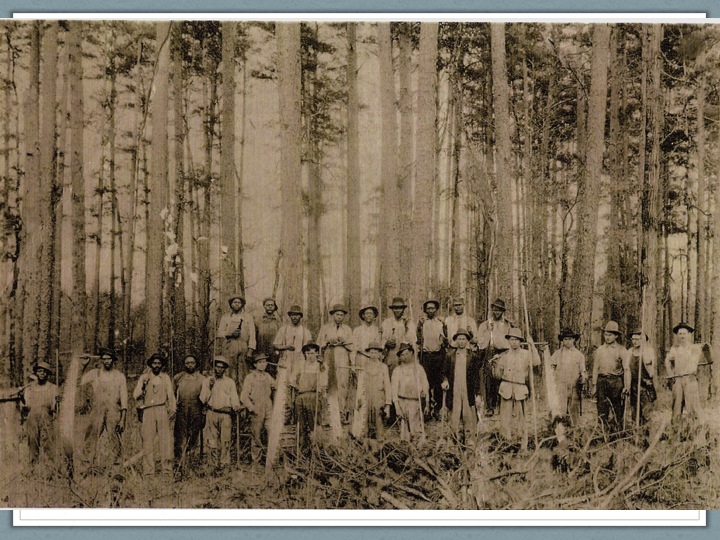

![Loggers in Clatsop County]()

Loggers in Clatsop County.

Loggers in Clatsop County Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi93132

-

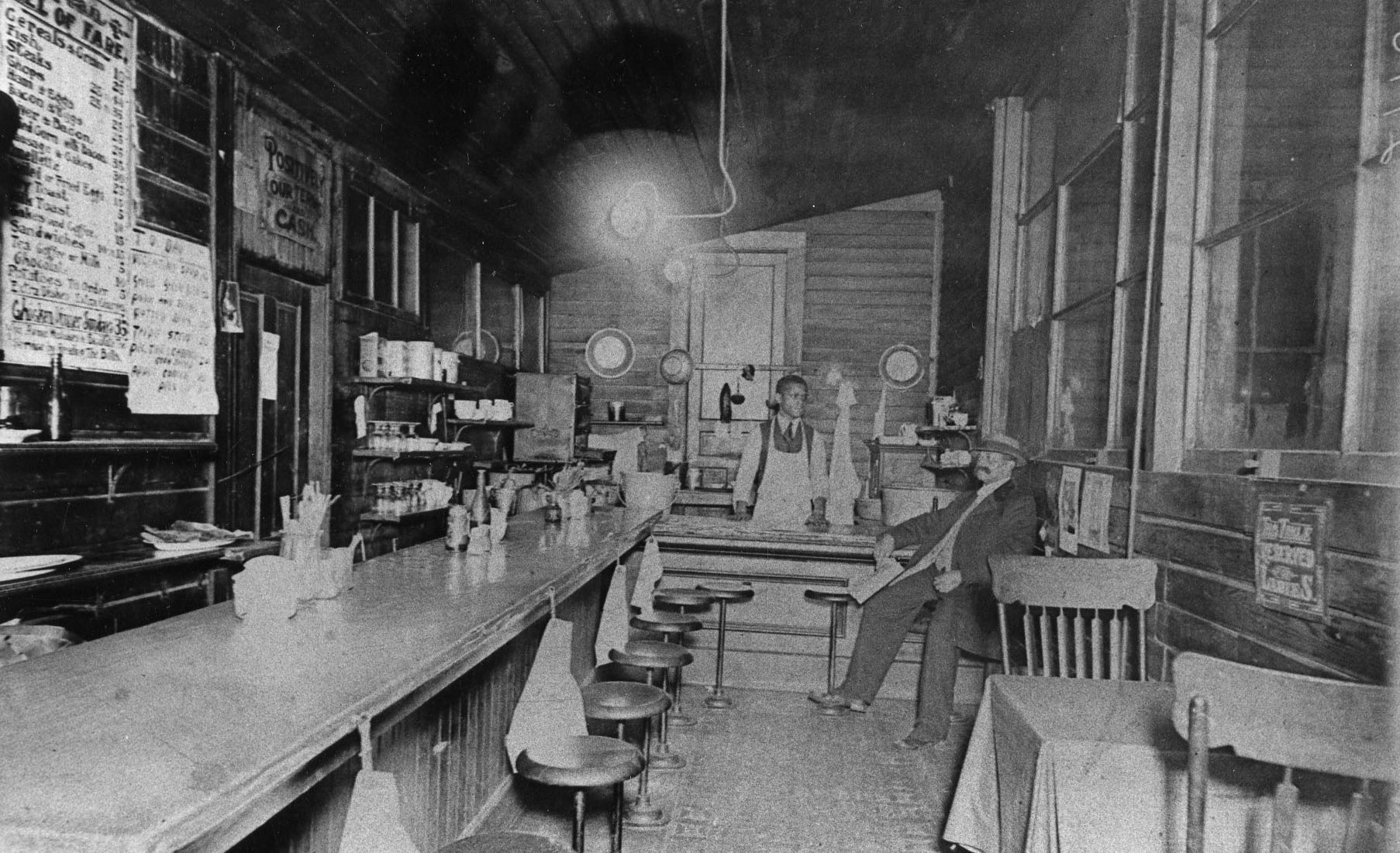

![Hegpeth Restaurant on Flanders Ave., Portland]()

Hegpeth Restaurant, Portland.

Hegpeth Restaurant on Flanders Ave., Portland Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![(L-R) George Morgan, Wyatt Williams, Mrs. Edward Cannady (Beatrice), Miss Holbert (no first name listed), Raymond Cage (seated).]()

Willamette Orchestra.

(L-R) George Morgan, Wyatt Williams, Mrs. Edward Cannady (Beatrice), Miss Holbert (no first name listed), Raymond Cage (seated). Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., org lot 679010

-

![Webb's Orchestra]()

Webb's Orchestra.

Webb's Orchestra Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi101260

-

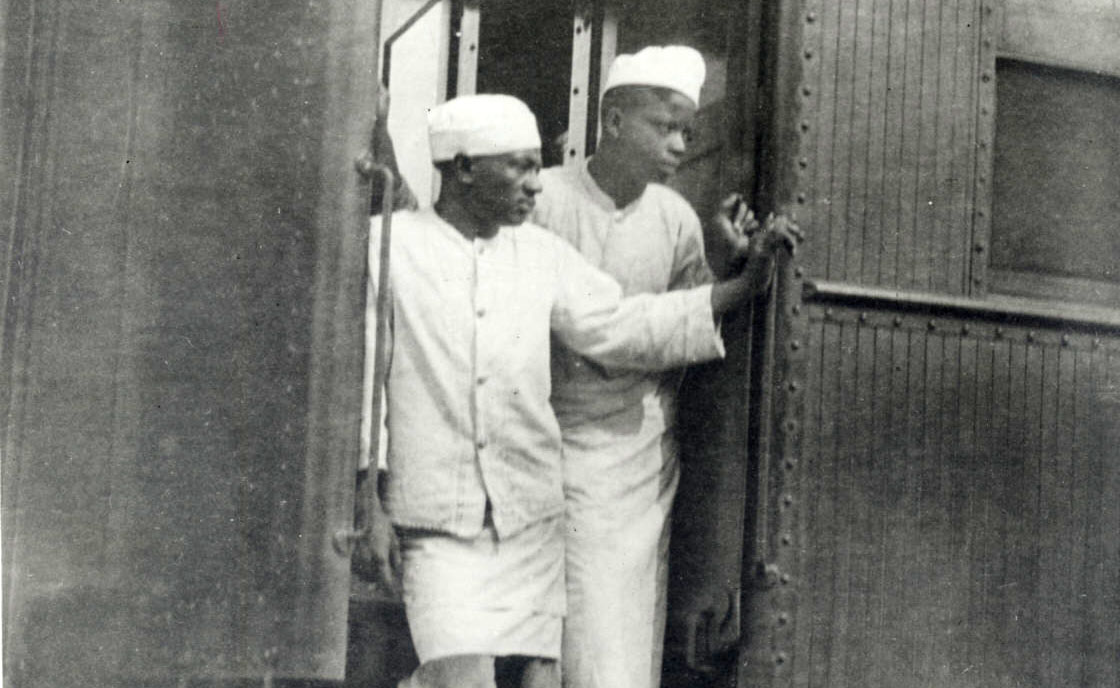

![Employees on the S&P railroad, 1919]()

Employees on the S&P railroad, 1919.

Employees on the S&P railroad, 1919 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 24250

-

![]()

Black Student Union walk-out, Oregon State University, 1969.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lot 1859

-

![]()

African Liberation Day, Irving Park, Portland, May 1979.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lot 1359

-

![]()

African Liberation Day, Irving Park, Portland, May 1973.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lot 1859

-

![]()

A family walks by the Albina branch of the Multnomah County Public Library, Portland, November 1968.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Lot 1959, Oregonian

Documents

Related Entries

-

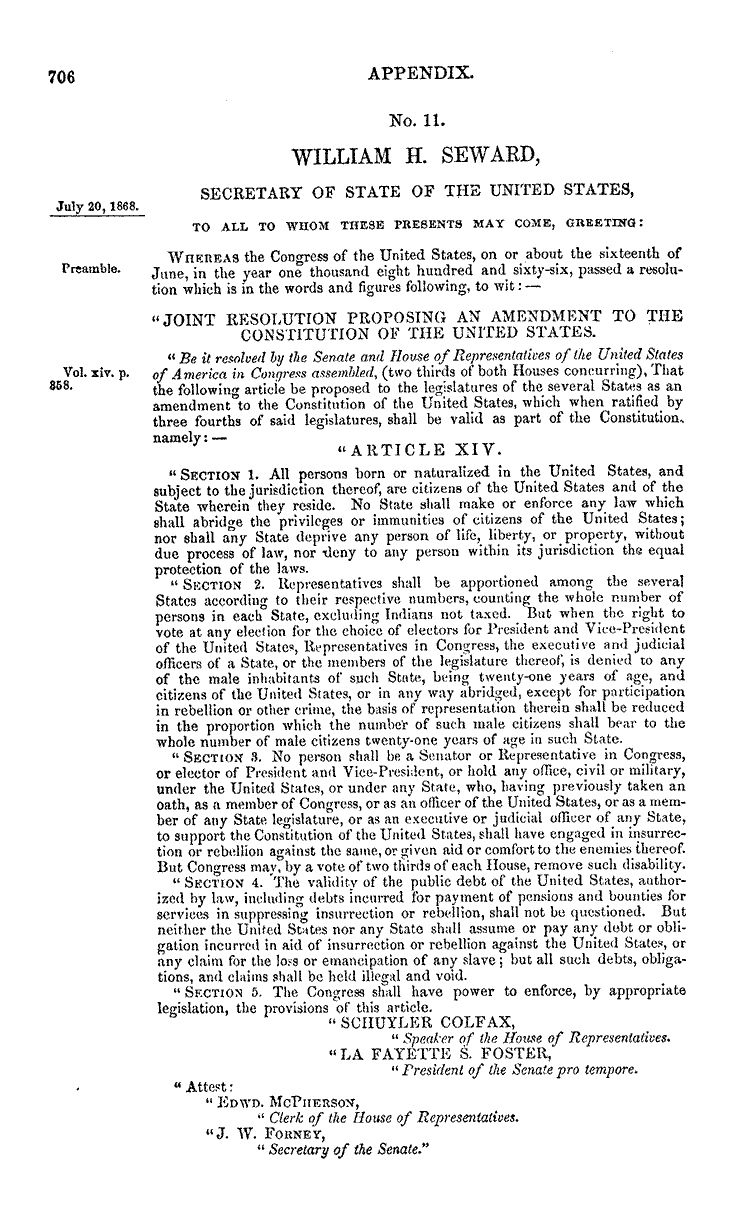

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![15th Amendment]()

15th Amendment

Civil War Reconstruction arguably culminated with the Fifteenth Amendme…

-

Albina area (Portland)

By the late 1880s, Albina, located across the Willamette River from Por…

-

![Avel Gordly (1947-)]()

Avel Gordly (1947-)

In 1996, Avel Louise Gordly became the first African American woman to …

-

![Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)]()

Beatrice Morrow Cannady (1889–1974)

Beatrice Morrow Cannady was the most noted civil rights activist in ear…

-

Billy Webb Elks Lodge

The Billy Webb Elks Lodge, a modest, shingle-sided building located at …

-

![Black Cowboys in Oregon]()

Black Cowboys in Oregon

The history of African American cowboys in Oregon begins well past the …

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black Panthers in Portland]()

Black Panthers in Portland

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) was founded in October 1…

-

![Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks]()

Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks

For thirteen months beginning in 1899, a company of 103 soldiers from t…

-

![Charles Ray Jordan (1937–2014)]()

Charles Ray Jordan (1937–2014)

Charles Ray Jordan was a towering figure in Portland history. The first…

-

![DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)]()

DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)

In 1929, Portland was a city deeply divided. Its small population of Af…

-

![George Bush (c. 1790-1863)]()

George Bush (c. 1790-1863)

George Bush, sometimes named as George Washington Bush in the historica…

-

![Golden West Hotel]()

Golden West Hotel

The Golden West Hotel, located at Northwest Broadway and Everett Street…

-

![Holmes v. Ford]()

Holmes v. Ford

On April 16, 1852, a former slave named Robin Holmes filed suit against…

-

![Jim Hill (1947-)]()

Jim Hill (1947-)

Jim Hill was the first person of color to be elected to statewide offic…

-

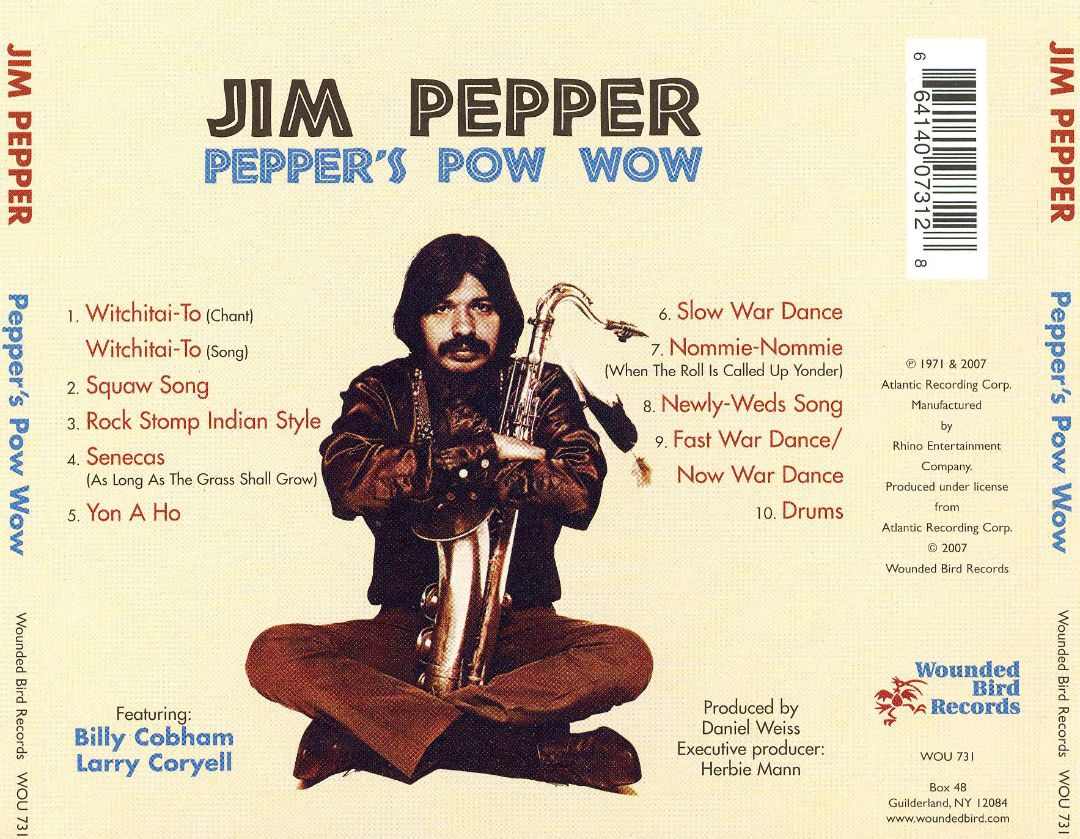

![Jim Pepper (1941-1992)]()

Jim Pepper (1941-1992)

Tenor saxophonist Jim Pepper was an internationally recognized and infl…

-

![Ku Klux Klan]()

Ku Klux Klan

Fiery crosses and marchers in Ku Klux Klan (KKK) regalia were common si…

-

![Lizzie Weeks (1879-1976)]()

Lizzie Weeks (1879-1976)

Lizzie Koontz Weeks was an African American activist in Portland in the…

-

![Maxville]()

Maxville

Maxville, in northeast Oregon east of the town of Wallowa, was home to …

-

![Salem's Colored School and Little Central]()

Salem's Colored School and Little Central

The first school open to African American students in Oregon—referred t…

-

![Thelma Johnson Streat (1912-1959)]()

Thelma Johnson Streat (1912-1959)

Thelma Johnson Streat was a multi-talented African American artist who …

-

![Triple Nickles -- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion]()

Triple Nickles -- 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion

The 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, nicknamed the "Triple Nickles" …

-

![Vanport]()

Vanport

In its short history, from 1942 to 1948, Vanport was the nation’s large…

-

![William A. Hilliard (1927-2017)]()

William A. Hilliard (1927-2017)

William A. Hilliard was the first African American editor of the Oregon…

-

![Willie Mae Young Hart (1915-2017)]()

Willie Mae Young Hart (1915-2017)

In addition to the community organizing that characterized so many of h…

-

![York (ca. 1770–?)]()

York (ca. 1770–?)

York was William Clark's slave and an integral member of the Lewis and …

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

BlackPast, The Online Reference Guide to African American History. www.blackpast.org

Millner, Darrell. "York of the Corps of Discovery." Oregon Historical Quarterly (Fall 2003).

Taylor, Quintard, Jr. In Search of the Racial Frontier: African American West, 1528-1990. New York: W.W. Norton, 1998.

Taylor, Quintard. "'There Was No Better Place to Go': The Transformation Thesis Revisited, African American Migration to the Pacific Northwest, 1940-1950." In Paul Hirt, ed., Terra Pacific: People and Place in Northwest America and Western Canada. Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1998.

McLagan, Elizabeth. Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940. Athens, GA: Georgian Press, 1980.