Eugene is a metropolitan center at the head of the Willamette Valley, approximately 110 miles south of Portland. The seat of Lane County, the city had an estimated population of 169,695 in 2018—nearly equal to the capital city of Salem. Eugene is known for outdoor recreation, bicycle and hiking trails, organic farming, a politically engaged citizenry, and a commitment to the arts. The University of Oregon, Lane Community College, and three private colleges are located there.

The region was home to the Chifin band of the Kalapuya, who lived there for thousands of years but whose numbers were decimated during the nineteenth century by introduced diseases, such as smallpox and malaria. When the first white settler, Eugene Skinner, arrived in 1846, he described the small valley between two buttes at a bend in the Willamette River as “beautiful, surrounded by these hills, reminding me of a bird’s nest.” He filed his land claim that July and returned in October to build a cabin partway up the butte closest to the river, known by the Kalapuya as Ya-Po-Ah, meaning “high place,” and now called Skinner Butte. Emigrants on the Applegate Trail used the cabin that winter while Skinner remained in Polk County. The Skinner family moved into their cabin in the spring of 1847.

A post office named Skinner’s was established in 1850, a town site was platted in 1852, and Eugene City was incorporated in 1862. Frequent flooding during the October-to-April rainy season earned it the nickname Skinner’s Mudhole. In 1864, the Eugene City name was changed to City of Eugene, which was shortened to Eugene in 1889.

Resettlers in the early 1850s connected two sloughs off the Willamette River, creating a millrace that ran through town to power grist mills and sawmills. Other businesses along the millrace included a furniture factory and a cold storage plant. A distillery was added in 1856; thirteen years later, it was producing seventy gallons of whiskey per day and paying more in taxes than any other business in the town of about eight hundred people.

Huge tracts of forest spread to the east, south, and west, and Eugene’s first sawmill opened in 1851, powered by water from the millrace. Other mills and wood-related businesses such as a sash and door factory followed, and the city grew into a center for processing and transporting lumber from mills in towns such as Springfield, Saginaw, and Cottage Grove. By the mid-twentieth century, almost half of Lane County’s workforce of 56,000 was employed in lumber-related jobs.

The Oregon and California Railroad arrived in 1871, connecting Eugene to Portland and points beyond. Wheat and oats were regular export crops, while fruit and vegetable packing became a significant industry, with farmers shipping out corn, cherries, walnuts, hazelnuts, and prunes. A farmers market, founded in 1915, lasted for more than forty years. The climate in the upper valley was particularly suited to growing hops, used for beer and malt liquor. Sometimes entire families would work the harvest, living in tents and getting paid a penny per pound.

The first public school was built in 1856, a year before the first church building—the Cumberland Presbyterian—was completed. When incorporation as a city was being debated in the early 1860s, the Eugene State Republican reported that some citizens suggested that money would be better spent on public education than on municipal government.

The University of Oregon opened in 1876, supported by a creative funding drive that included contributions of livestock and produce that could be converted to cash. The school grew into a bedrock of the community, weathering an attempt during the Great Depression to consolidate it with Oregon State College (now Oregon State University) in Corvallis.

By the early 1900s, Eugene was proclaiming itself the Immigrant’s Mecca. The Commercial Club and the Chamber of Commerce sent out brochures and bought advertisements in nationally distributed publications such as Sunset and Pacific Monthly. Special editions of local newspapers were sent East, describing the farmland near Eugene as an agricultural paradise, with claims that the soil produced four-pound potatoes, thirty-pound cabbages, and cornstalks fourteen feet high.

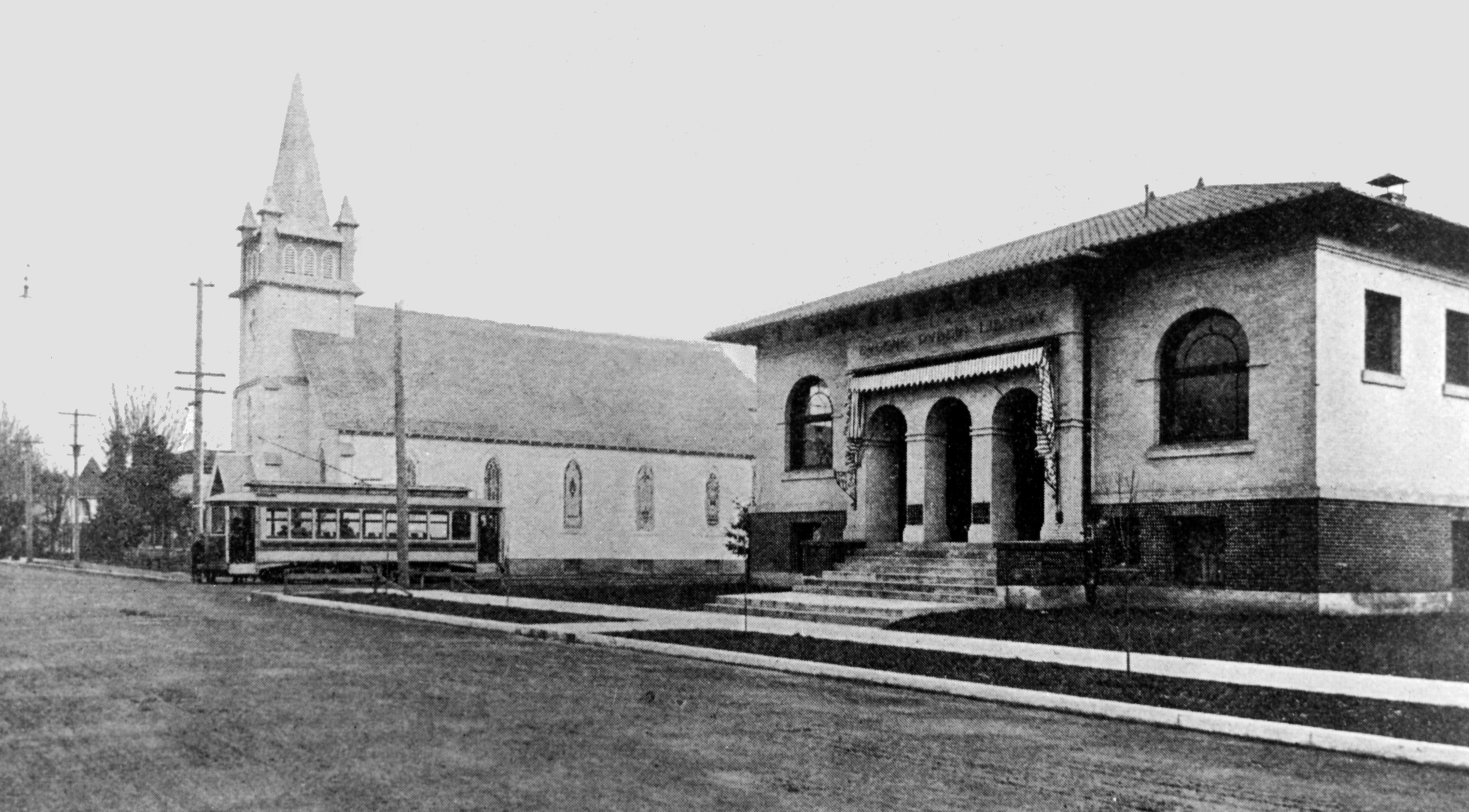

The population of the city more than tripled during the first two decades of the twentieth century, growing from 3,236 in 1900 to 10,600 in 1920. The first automobile arrived in 1904, a public library opened in 1906, and electric streetcars began running the following year.

At times, Eugene has been ahead of the nation in both progressive and conservative politics. A decision recognizing women’s right to vote in Lane County passed in 1900, a decade before women were accorded the vote statewide and twenty years before the nation passed the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The city voted in 1911 to prohibit alcohol, under the “local option” law, nine years before the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified. Across the Willamette River, the town of Springfield remained “wet.” On Saturday nights after that city’s bars closed, a special double streetcar rumbled back to Eugene, carrying its intoxicated cargo and attended by a sheriff’s deputy.

Racial inequality in the city was the standard for many years. When the Ku Klux Klan paraded through Eugene in 1924, the Daily Guard reported “huge crowds.” The day ended with a fireworks display and a large cross-burning on Skinner Butte that cast a “reddish glow” over the town. Laws and covenants excluding nonwhites from certain neighborhoods existed until the 1950s, and crimes such as vandalizing a Jewish synagogue occurred as recently as 2017.

Calls for more diverse naming of city landmarks resulted in a University of Oregon dormitory, originally named for Frederick Dunn, an early professor and member of the Ku Klux Klan, being renamed in 2017 for DeNorval Unthank Jr., the first African American to earn a degree in architecture from the university. In 2018, the Eugene City Council voted unanimously to rename the Westmoreland Community Center for Dr. Edwin Coleman II, an African American and longtime English professor at the university, and to rename the Royal Elizabeth Park in west Eugene for Andrea Ortiz, the city’s first Latina city councilor.

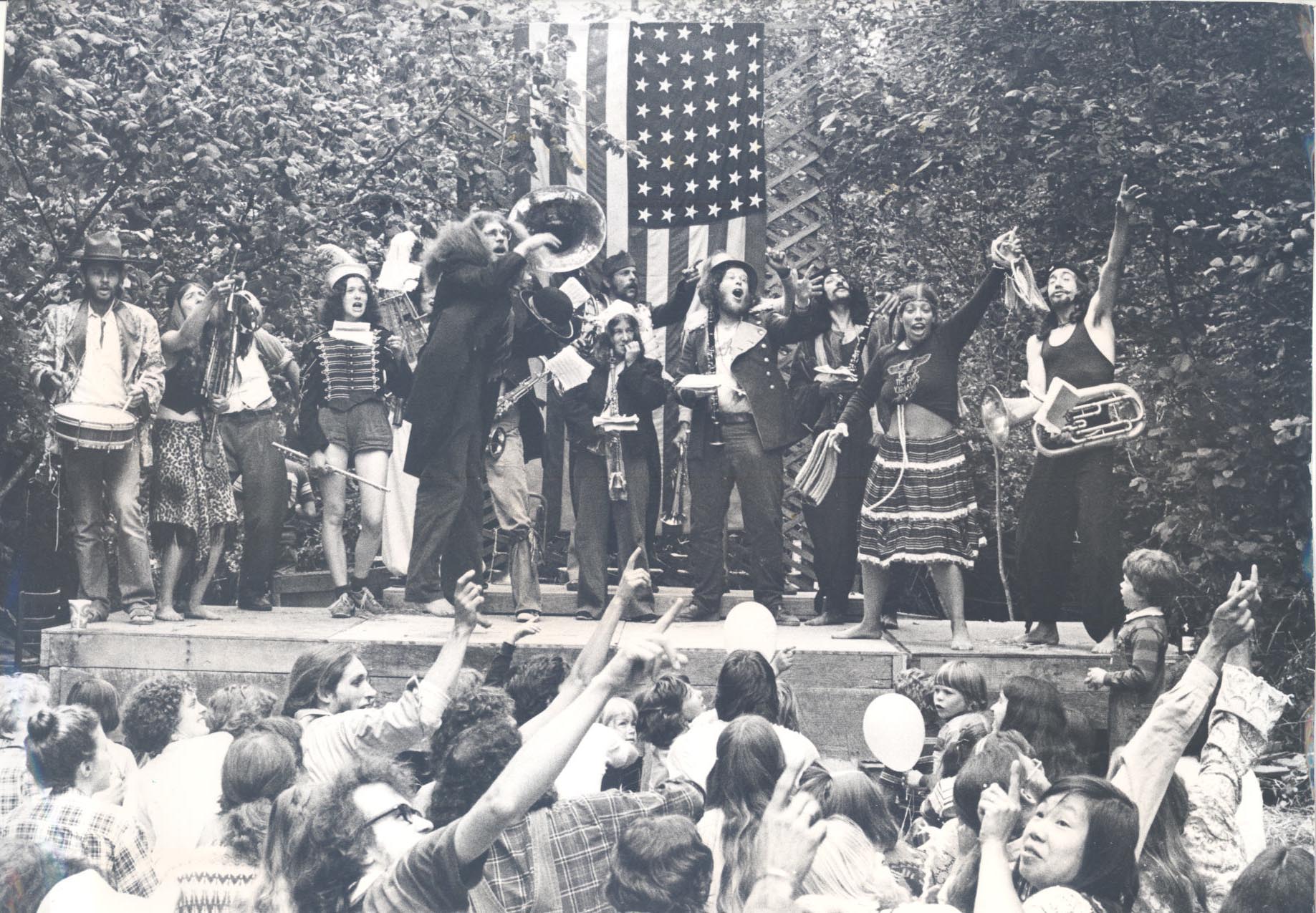

With the influx of baby-boomer students, University of Oregon enrollment topped 10,000 in 1963 and reached more than 17,000 six years later. Through the late 1960s and into the 1970s, Eugene gained a reputation for liberal thinking and alternative lifestyles. Saturday Market, now a weekly institution in downtown Eugene, began on a rainy spring morning in 1970 with a handful of vendors. That same year, an organization named White Bird began offering services in comprehensive health care. Natural foods stores such as The Kiva (1970) and Sundance (1971) opened. BRING Recycling began in 1971, and volunteers collected 400 tons of glass that first year. The Lane County Farmers Market reopened in 1979 and operates twice a week through the spring and fall. The Oregon Country Fair, first held in 1969, draws tens of thousands for its three-day event each summer.

Beginning in 1964, Eugene was visually dominated by a fifty-foot-high concrete cross that a local businessman installed on public property on top of Skinner Butte. The controversy that followed prompted a 1965 story in the Saturday Evening Post, which reported that while Eugene was in many ways politically progressive it also had the highest proportion of churchgoers in Oregon. After thirty years, three trials, and eight court rulings, the cross was removed in 1997 and placed at the Eugene Bible College (now New Hope Christian College) at the south end of the city.

The urban renewal movement of the early 1970s led to many older downtown buildings being razed in Eugene, and larger department stores moved to a new suburban mall, the Valley River Center. Sections of Willamette Street and Broadway, which cross at the city core, were closed to automobile traffic in an attempt to create a pedestrian-friendly shopping area, but businesses struggled and vacant storefronts were common through the 1980s and 1990s. By the end of the twentieth century, all but one block of the two streets had been reopened to vehicle traffic.

Eugene has long valued parks and open spaces. During its earlier years, residents planted and maintained shade trees throughout the residential blocks. Hendricks Park, a forested hillside on the east end of the city, was created from land donated in 1906. During the Great Depression, city residents voted in 1938 to tax themselves and purchase Spencer Butte, a hill outside the city limits which is now a popular hiking destination. In 1970, the city created the Eugene Bicycle Committee to provide a comprehensive plan for creating bike lanes and building dedicated paths. As of 2019, the city has more than forty miles of bike paths, including the 19.5-mile Ruth Bascom Riverbank Trail System.

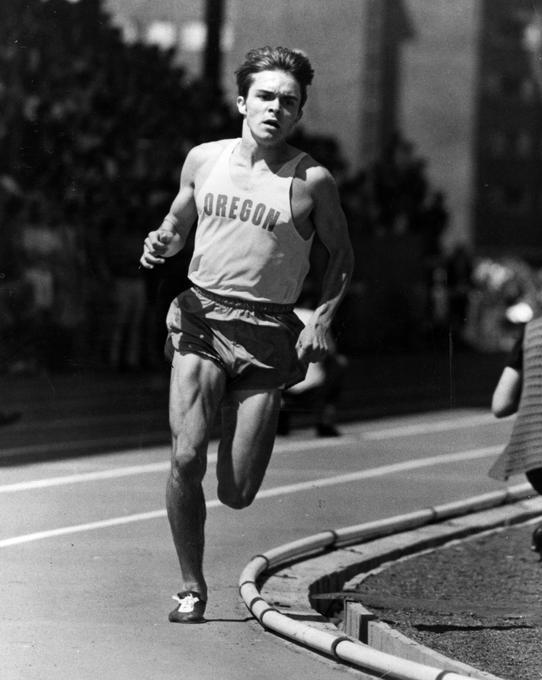

Eugene is often referred to as Track Town, USA, where legendary coach Bill Bowerman coached runners such as Steve Prefontaine, Kenny Moore, Bill Dellinger, and Phil Knight, who later founded Nike. The city is also the birthplace of jogging in America, a movement started in 1963 after Bowerman visited New Zealand and saw people of all ages regularly running in groups at a slow, steady pace. When Bowerman placed an announcement in the local newspaper calling for people interested in feeling healthier to meet at the university intramural field, more than 200 people showed up.

The city is the cultural center of the upper Willamette Valley—home to the Eugene Symphony, the Eugene Ballet, the Eugene Opera, and the Oregon Bach Festival. The Hult Center for the Performing Arts, the Cuthbert Amphitheater, and the Shedd Institute regularly host national and international acts, and the Very Little Theatre, begun in 1929, is one of the longest-running community theaters in the country. Media outlets include the Register-Guard and Eugene Weekly newspapers, six television stations, and more than a dozen radio stations. The famous “chicken salad sandwich” scene by Jack Nicholson in the 1970 film Five Easy Pieces was shot at a Denny’s restaurant on Interstate 5 just south of town. The comedy classic National Lampoon’s Animal House was filmed in Eugene and surrounding areas in 1977.

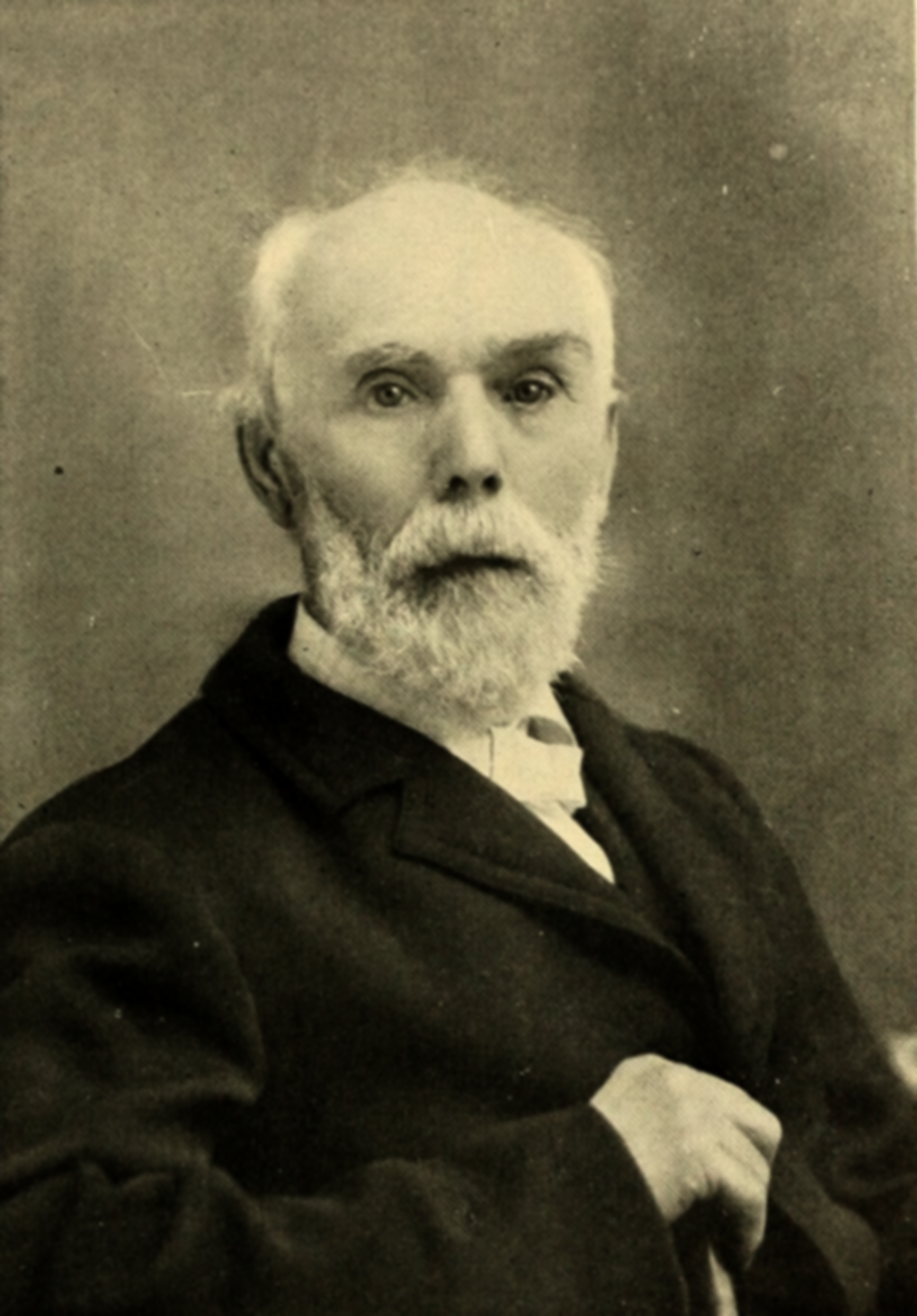

Eugene has been home to Oregon governors John Whiteaker, Neil Goldschmidt, John Kitzhaber, and Ted Kulongoski. Senator Wayne Morse lived there for many years, and his ranch in the south part of town is now a city park. Counterculture icon and writer Ken Kesey has been long associated with Eugene, although he lived east of town in Pleasant Hill. Other noted residents include artist Maude Kerns, actor David Ogden Stiers, and writers Richard Brautigan, Damon Knight, and Kate Wilhelm.

Eugene has grown steadily during the twenty-first century, from 140,600 in 2000 to an estimated 166,575 in 2016. Enrollment at the University of Oregon has increased from 17,800 in 2000 to 23,600 in 2016. Large sports complexes have been built for football, basketball, baseball, and softball, feeding a strong identification with the university’s athletic teams and sports insignia. The school has consistently been one of the area’s top employers, with more than 5,500 employees in fiscal year 2017, second only to the PeaceHealth Medical Group.

The city’s downtown has seen a resurgence through construction of student housing projects, hotels, and businesses that support them. In 2012, a consortium of technology companies began promoting the region as the Silicon Shire, and two years later Lane County had 400 technology-related firms employing 4,500 people with a combined payroll of nearly $300 million. In 2015, Fast Company magazine named Eugene one of the “Next Top 10 Cities For Tech Jobs.” Microbreweries, led by Ninkasi, Hop Valley, and Oakshire, have done so well that a neighborhood on the west side of town is referred to as the brewery district.

Projects such as Envision Eugene, a long-term land use plan, and the city’s 2018 purchase of the Eugene Water and Electric Board’s vacant riverfront property in an effort to create a mix of residential and commercial buildings along the Willamette River, are key elements of the city’s focus on balancing social, economic, and environmental concerns in the twenty-first century.

-

![]()

Willamette Street, Eugene, looking north.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba009167, 24100, photo file 361b

-

![]()

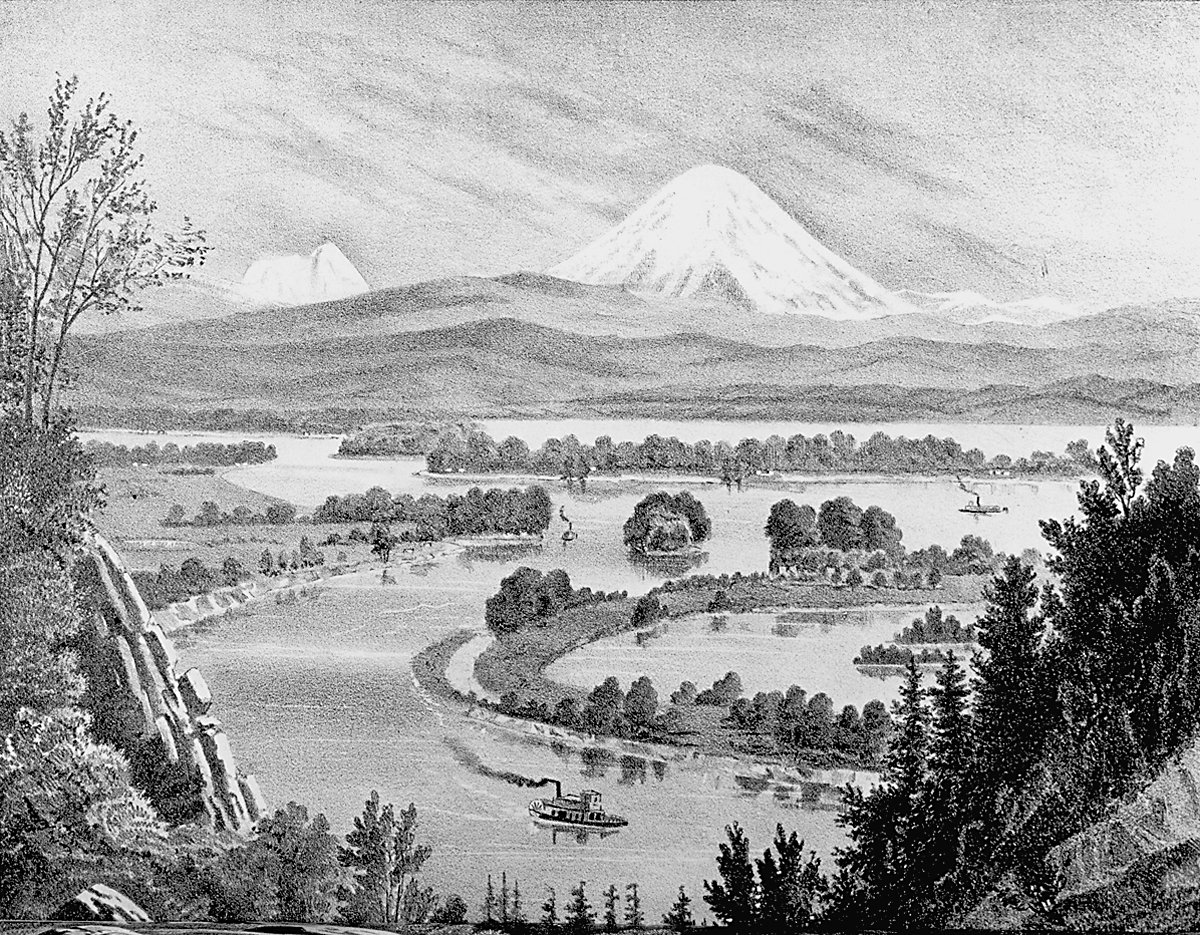

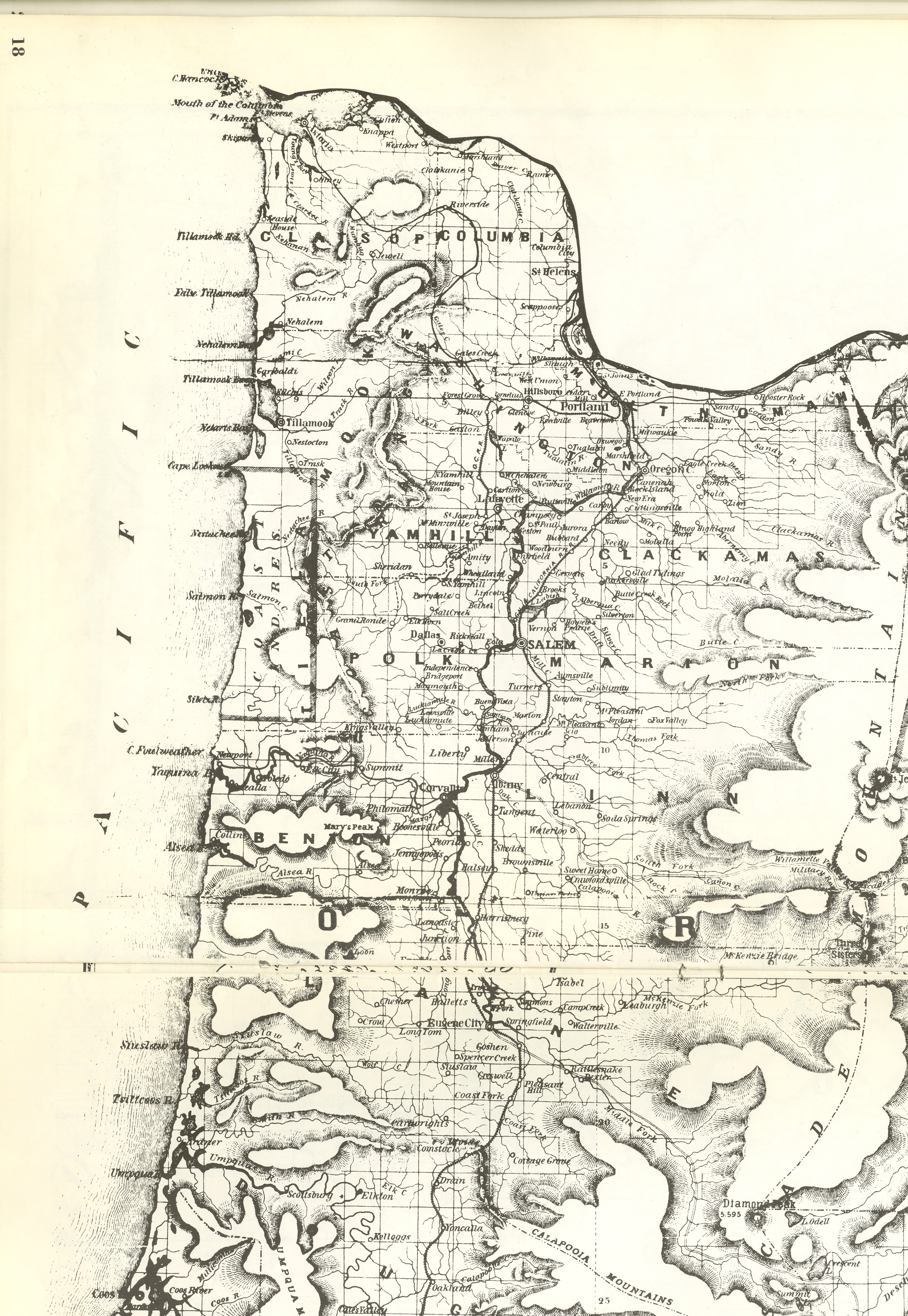

Eugene City, 1859.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba009107, Orhi4861, photo file 361A

-

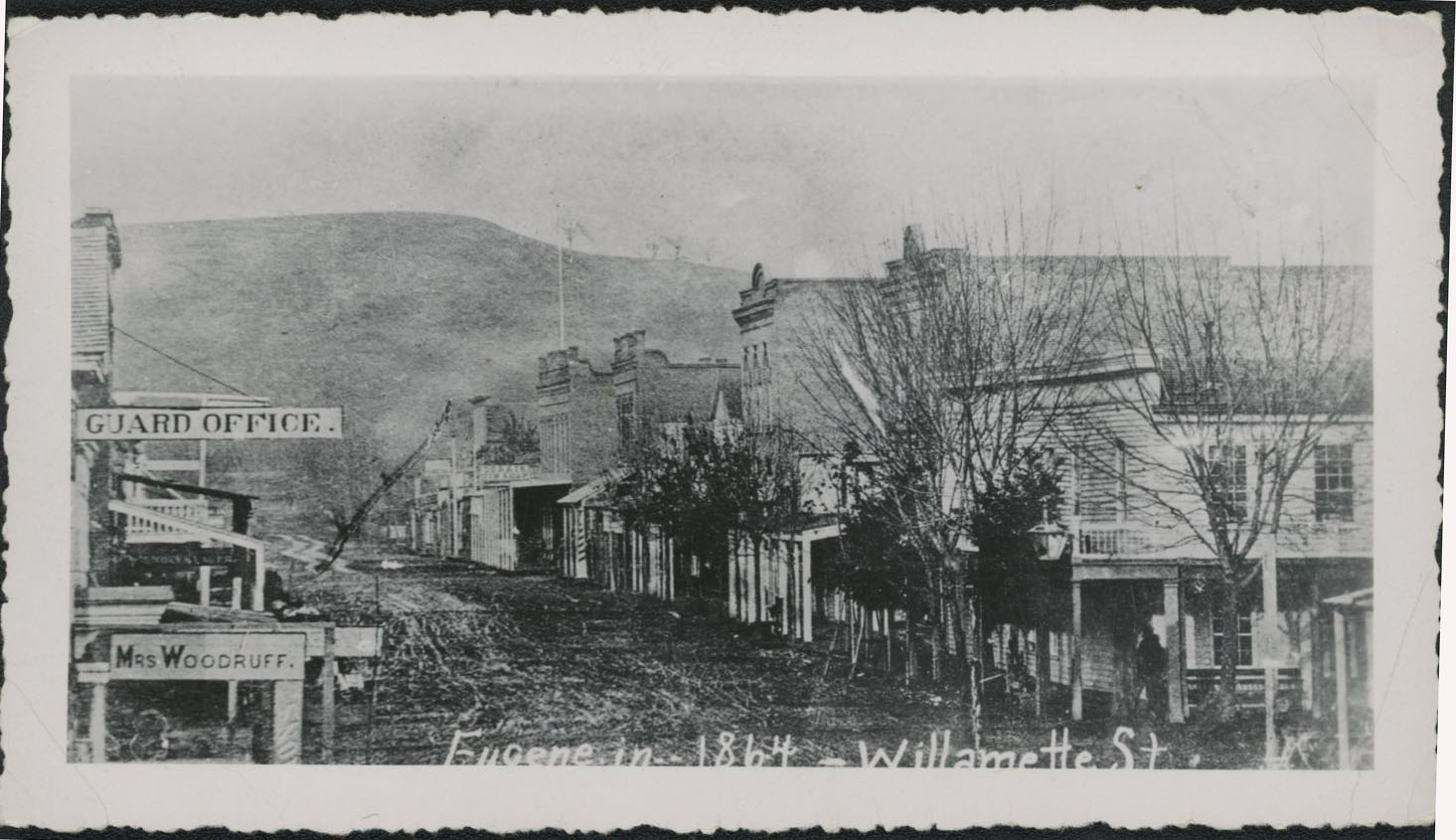

![(Date on photo is incorrect)]()

Eugene, c. 1871.

(Date on photo is incorrect) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi24894, ba009168, photo file 361b

-

![]()

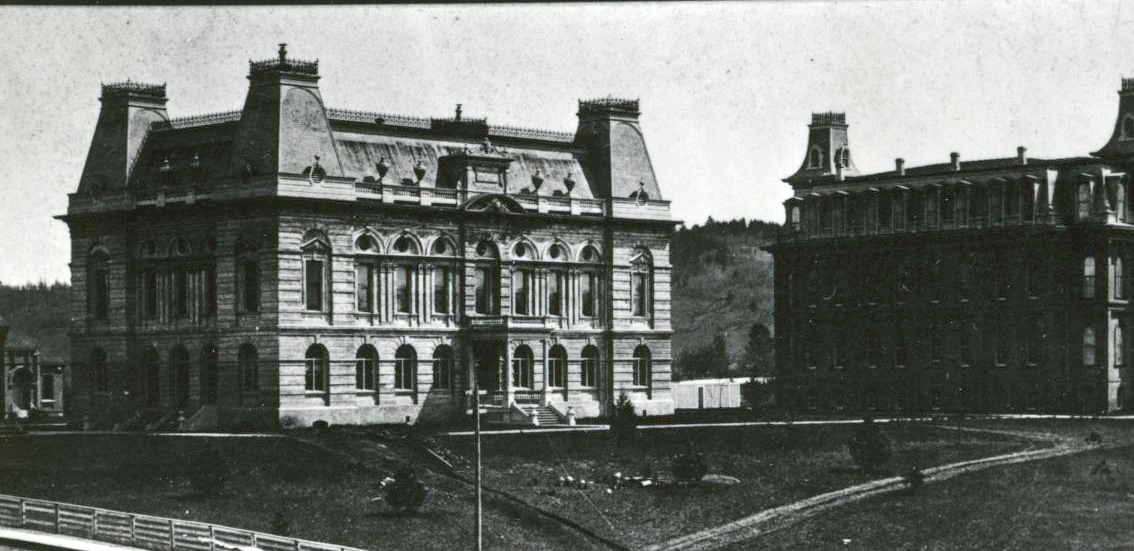

Villard Hall (left), University of Oregon, Eugene, 1888.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 007507

-

![]()

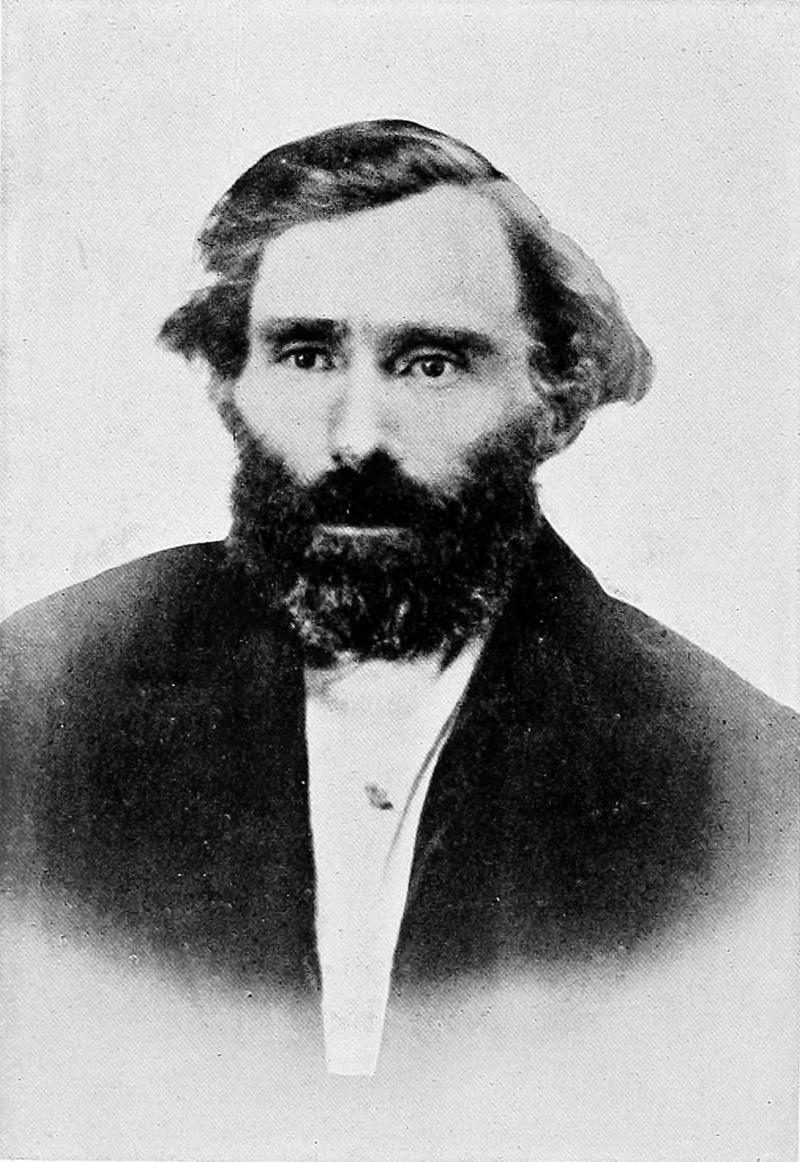

Eugene Skinner.

From Joseph Gaston's Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912 (published in 1912)

-

![]()

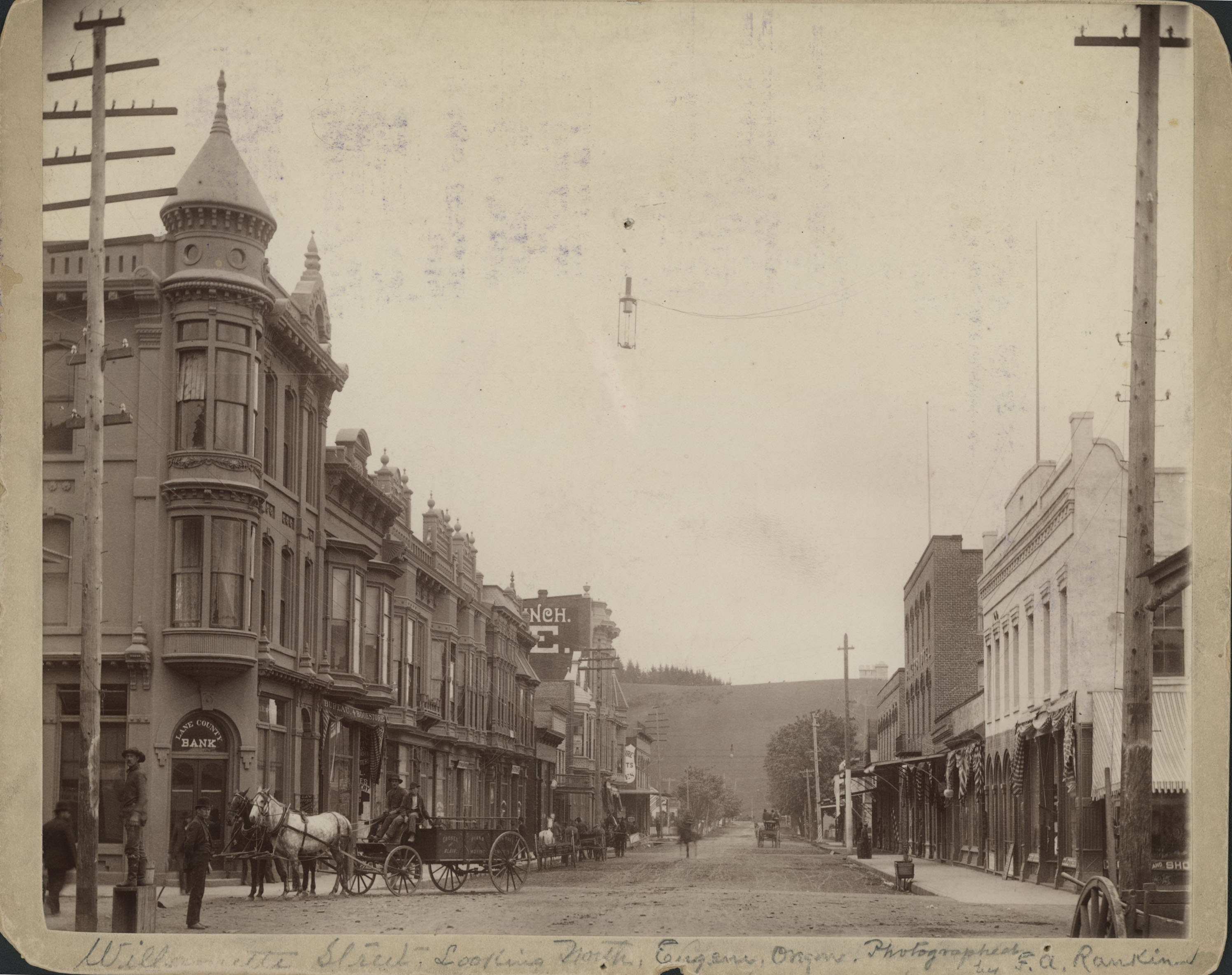

Willamette Street, Eugene, looking north, 1903; old U of O observatory on top of Skinner's Butte.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 24889. photo file 361b

-

![]()

Willamette Street, Eugene, 1896.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba009165, 55756, photo file 361b

Related Entries

-

![Animal House (film)]()

Animal House (film)

National Lampoon’s Animal House, one of the most successful American fi…

-

![Bushnell University]()

Bushnell University

Bushnell University was founded in Eugene in 1895 by Eugene C. Sanderso…

-

![DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)]()

DeNorval Unthank (1899-1977)

In 1929, Portland was a city deeply divided. Its small population of Af…

-

![Eugene streetcar system]()

Eugene streetcar system

The first street railway in Eugene was a mule-powered system that began…

-

![Eugene Water & Electric Board (EWEB)]()

Eugene Water & Electric Board (EWEB)

In the aftermath of a 1906 outbreak of typhoid fever in Eugene, which w…

-

![John Whiteaker (1820–1902)]()

John Whiteaker (1820–1902)

John Whiteaker, a self-educated farmer from Lane County, was elected in…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Ken Kesey (1935-2001)]()

Ken Kesey (1935-2001)

A farm boy from the Willamette Valley, Ken Kesey brought an earthy, ind…

-

![Lane Community College]()

Lane Community College

Lane Community College (LCC) in Eugene opened its doors in 1965, but th…

-

![Oregon and California Lands Act]()

Oregon and California Lands Act

The Oregon and California Lands Act, heralded as a forward-looking cons…

-

![Oregon Bach Festival]()

Oregon Bach Festival

In the summer of 1970, two young choral conductors—one from Stuttgart, …

-

![Oregon Country Fair]()

Oregon Country Fair

Founded in 1969, the Oregon Country Fair (OCF) is a self-sustaining ann…

-

![Steve Prefontaine (1951-1975)]()

Steve Prefontaine (1951-1975)

For Steve Prefontaine, running was a way to find confidence, a way to s…

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

-

![Willamette Valley]()

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bettis, Stan. Market Days. Eugene, Ore.: Lane Pomona Grange, 1969.

Card, Douglas. From Camas to Courthouse: Early Lane County History. Eugene, Ore.: Lane County Historical Society, 2008.

Holt, Kathleen, and Cheri Brooks, eds. Eugene 1945-2000: Decisions That Made a Community, Eugene, Ore.: City Club of Eugene, 2000.

League of Women Voters of Eugene. Eugene . . . and its Government. Eugene, Ore.: City of Eugene, 1962.

Moore, Lucia, Nina McCornack, and Gladys McCready. The Story of Eugene. New York: Stratford House, 1949.

“The Century.” Register-Guard, March-December 1999.

Tweedell, Bob. Millrace History. Eugene, Ore.: The Register-Guard, 1949.