The Portland Metro area rests on traditional village sites of Native peoples. These include those of Chinookan-speaking (or Kiksht-speaking) peoples, such as the Multnomah, Cascade, Clackamas, and Clowwewalla, who made their homes along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers, creating communities and summer encampments in areas rich in natural resources. The Tualatin Kalapuya were the ancestral people in present-day Washington County, and their homelands include portions of West Portland and the towns of Hillsboro, Forest Grove, Beaverton, and Tigard. The traditional homelands of the Molalla people of the northeast Willamette Valley and Cascade Range include areas as far north as Oregon City. In the twenty-first century, Native American residents of urban areas include people from across the region and the larger United States. Enrolled members of Northwest tribes who live in urban areas often have ancestral treaty rights to fish and gather along riverways. Some citizens or descendants of Indigenous people represent degrees of tribal affiliation; some are enrolled, some are not, but all have significant ancestral ties to their tribes and tribal homelands.

“‘Urban’ is not a kind of Indian,” Terry Straus and Debra Valentino (Oneida) wrote. “It is an experience, one that most Indian people today have had.” For generations, many Indigenous people have lived away from their tribal homelands, and Urban Indians from all over the United States are residents of Oregon. Approximately 40,000 Urban Indians live in Portland, the ninth largest such community in the United States, and others live in all thirty-six counties.

Urban Indians have no legal status distinct from Indians who live on reservations. They commonly have social, cultural, or economic ties with both reservation communities and with other Indians who live in their city, while other connections are intertribal and from the result of mixed marriages. Most self-identify as both Urban Indians and as members of tribes.

Among Indigenous individuals and families in Oregon cities, some have assimilated into the fabric of mainstream city life in much the same way that some members of immigrant groups have, by disconnecting from their cultural identity and community. For centuries, this form of “invisibility” has been promoted by non-Native associations as a way to avoid cultural and racial censure.

Native Hubs

“Native hub consciousness,” as defined by anthropologist Renya K. Ramirez (Winnebago), refers to the spaces where Urban Indians have created Native diaspora that connects them to ancestral lands and cultures from a distance. Native hubs, organizations, groups, cultural events, and media provide for intertribal networks. By sustaining a sense of connection to both the city and ancestral homelands, Urban Indians are able to live at the intersection of multiple cultural and national identities. Local Native hubs make this integration possible.

Indigenous people living in cities tend to remain connected to their homelands. As a result, diasporic connections among Urban Indians create and sustain a powerful Native hub consciousness through the recreation of cultural and ancestral relationships in new spaces. For Portland’s Native community, that consciousness has been created through intertribal connections that have survived over generations.

Sovereignty and Trust Obligations

During the intense resettlement period of the mid-nineteenth century, non-Native emigrants claimed land and built towns on land that Indigenous people had inhabited for thousands of years. In an effort to protect their traditional ways of life, tribes ceded their homelands through negotiated treaties or executive agreements with the United States. As a result, 2.5 million acres of land in the Oregon Territory, including all of Portland, were opened to white settlement, and Native residents were removed to reservations.

Oregon has nine federally recognized Indian tribes, whose members are citizens of sovereign nations. Federal recognition, whether by treaty or executive agreement, connects tribal members to the U.S. government, as beneficiaries of trust obligations. In this way, federally recognized tribal members, on or off reservations, have a type of dual citizenship.

Because Congress ratified nation-to-nation treaties with tribes and bands in order to take legal ownership of their land, the government is required to fulfill trust obligations to protect remaining tribal lands, resources, and rights to self-government and to provide services necessary for tribal survival and advancement. Congress has been mandated to maintain trust obligations and authority over Indian affairs in order to ensure American Indians a life of health and decency.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service are the primary federal agencies that were created to provide direct services to reservation communities. Despite an increase in the numbers of Native people living in cities—by the end of the twentieth century, approximately three-quarters of Indians lived away from their reservations—both agencies have struggled to serve them. Because enrolled tribal members live in urban centers, they are not eligible for all services due to reserved treaty rights (although locally enrolled tribal members may have fishing and gathering rights in Oregon unique to enrollment).

Urban Indians in Twentieth-Century Oregon

Since the mid-nineteenth century, the unpredictable fulfillment of trust obligations by federal agencies has contributed to the socioeconomic decline of many reservations in Oregon.

Federal Indian Relocation Policy (1952-1973). After World War II, the Indian Relocation Act in 1956 encouraged people to relocate from reservations into cities such as Portland for jobs and vocational training. The act was in support of the U.S. government’s continuing efforts to assimilate Indians into white culture and to facilitate Termination policies passed by Congress. Indians would continue to leave reservations to work and attend school throughout the twentieth century. For many, the federal programs did not work, and relocated Indians struggled to find jobs, housing, and medical care. While most Urban Indians remained connected to their homeland communities others actively assimilated into their new communities but also maintained contact with families and tribes. Relocation also left thousands of Indians unprepared for city life. They were hampered by social and cultural barriers, including language and spiritual and religious traditions, and had little or no access to resources or services. Nevertheless, Native people in Oregon found ways to protect and sustain their tribal identities.

Oregon Termination Act (1954) and Restoration (1970-1980s) Policy. During and after World War II, large numbers of people, including American Indians and Alaska Natives, migrated from rural communities to cities for jobs and opportunities. A major cause of that movement was federal Termination policy--laws and resolutions that Congress passed during the 1950s to terminate the government’s trust relationship with over one hundred tribes and bands in the United States, including 61 tribes in western Oregon. The law nullified treaty agreements by granting in exchange a series of per capita payments for land and resources. Many reservations in Oregon were dissolved, land was sold, and assimilation policies were implemented to terminate the federal-Indian trust relationship.

Beginning in the 1970s, tribal leaders began to lobby Congress to reverse Termination policies and restore trust relationships and treaty obligations through a legal process called Restoration. By 1977, some terminated tribes had been restored and reinstated, although with a significant loss of homelands and resources. Having survived Termination and regained federal recognition as sovereign nations, restored Oregon tribes control their own destinies.

Military Service. Those who serve in the military in all capacities and eras are deeply respected warriors in Native communities. Indian veterans of World War I were granted American citizenship in 1919, five years before Congress granted citizenship to all American Indians in 1924. During World War II, more than 25,000 Native men and women across the country served in the armed services, and thousands more worked in war industries. As a major shipbuilding center, Portland and Vancouver, Washington, attracted Native workers, many of whom lived in Vanport City. After the war, many chose to remain in the city rather than return to the sometimes difficult conditions on their reservation.

Many veterans resettled in Oregon cities to take advantage of jobs and to have access to assistance programs and the Veterans Administration hospital, provided by the 1944 GI Bill. Many of those who relocated to cities stayed with family and friends, often moving between the city and the reservation for financial, housing, medical, and other support services.

Activism and Community

The fight to preserve tribal sovereignty and treaty rights has long been at the forefront of the American Indian civil rights movement. Supported by Indian students, the community, and non-Native allies, the American Indian Movement (AIM) moved issues forward through marches and demonstrations directed at alleviating and addressing injustices and a lack of services. In one protest in 1972, members of AIM and their allies occupied federal offices in Portland as part of the Trail of Broken Treaties, a national protest. They used the same method in August 1975 when protesters took over Bonneville Power Administration headquarters office in Portland.

Protest movements by local chapters of AIM aligned with the cultural focus of organizations such as Anpo Cultural Camp, whose purpose was to renew traditional beliefs, ceremonies, and sacred spaces. Anpo, which means “dawn” in the Lakota language, held sweat lodge and Sundance ceremonies in collaboration with the community leadership. Youth and family-centered services were based on a cultural healing model of maintaining sobriety and reawakening traditional beliefs and ceremony. The camp, originally located in Estacada in the 1970s, was later relocated to U.S. Forest Service land that had been set aside for Native healing and ceremony. It is a prime example of a Native hub associated with a community. These hubs and centers evolved from the work done by young people in the Urban Indian community during the second half of the twentieth century. Although Anpo Camp has survived into the twenty-first century in name and location, it is now disassociated with the original Anpo model.

The federal government’s self-determination policy, enacted under President Richard Nixon, remains the guiding principle of Indian policy. In a message to Congress in 1970, Nixon said that “the time has come to break decisively with the past and to create the conditions for a new era in which the Indian future is determined by Indian acts and Indian decisions.” The president singled out Indian health and the growing Urban Indian population as “the most deprived and least understood segment of the urban population.”

The Indian Health Service, created by the federal government, did not adequately address the health needs of Urban Indians until 1992, when it created thirty-four urban health programs and helped fund the Native American Rehabilitation Association (NARA) in Portland, founded in 1970. Urban Indians not only share the same health problems that exist in the general Indian population, but their health problems are exacerbated by the mental and physical hardships associated with dislocation from family and traditional cultural environments. Urban Indian youth continue to be at greater risk for mental health and substance abuse problems, suicide, gang activity, teen pregnancy, abuse, and neglect.

The socioeconomic needs of the growing Urban Indian community compelled activists to collaborate with other communities of color. By supporting social services, allies--some representing non-Indigenous communities--helped ease the inequality and inequity Indians experienced. The Chicano Indian Study Center of Oregon (CISCO), formed in 1973, was one of the first nationally recognized Native hubs created by an alliance of Indigenous community members. It provided education, housing, child care, and a health center and included an alcohol and drug treatment program that honored traditional spiritual practices.

Native groups formed other community service organizations, including the Urban Indian Council (UIC), organized as an advisory board of peers modeled after tribal councils. The UIC was formed with representatives of NARA, Urban Indian Program, United Indian Students for Higher Education, Portland American Indian Center, Native American Youth Association, Bow and Arrow Culture Club, and others. The Council provided direction to, for, and by its representative membership. By the late 1970s, Urban Indians knew where traditional sweats were held, where handcrafted regalia could be found, where they could find powwows, how to locate the Indian Education office for tutoring assistance, and where to take classes on basket weaving. Title VI of the Indian Education Act (1972) provided a sense of inclusiveness for Native children in Portland, and the Native American Youth and Family Center provided a social-cultural experience for youth.

During the mid-1980s and 1990s, Urban Indian programs were nationally recognized for expanding service capabilities. Native hub groups began to emphasize broadening cultural expertise, including teaching Native languages in local community centers. The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community and the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians opened offices in Portland and offered social services and culture classes to the urban Native community.

Urban Indians in the Twenty-first Century

By 2017, 78 percent of Indians were living off reservations. For decades, many had worked to retain their cultural identities and had participated in creating and enhancing Native hub consciousness by advocating for the growth of resources and services for Native families in the cities where they lived. Tribal identity among Urban Indians remains intact and is affiliated strongly with homelands. Both reservation and Urban Indians, for example, typically introduce themselves to each other by first sharing their tribal affiliation and then their family name.

Young Urban Indians continue to be drawn to Native hubs in Portland and other Oregon cities, and they have used those connections to become involved in environmental policy-making, economic sustainability, and entrepreneurial projects. Pacific Northwest tribes and Urban Indian programs, often in partnership with each other, continue to collaborate with local governments to fight unemployment, increase the tourism and gaming market, and build intragovernmental efforts.

Urban Indians in Portland are now represented in Portland government, art, education, and business, and their influence is apparent on the city landscape. In 2015, Greg A. Robinson (Chinook) created artwork for a new bridge over the Willamette, Tilikum Crossing (“Bridge of the People in Chinuk Wawa), which was gifted to Tri-Met by the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community. Paul Lumley (Yakama) received the 2017 Spirit of Portland (SOP) award for environmental stewardship; and Clorissa Alexis Ann Stamp (Nez Perce/Northern Arapaho) received the 2017 SOP Outstanding Young Leader award. Elizabeth Woody (Warm Springs, Navajo, Wasco, Yakama) was named Oregon’s poet laureate in 2016, and Tawna Sanchez (Shoshone-Bannock, Ute, Carrizo) is an Oregon state legislator. Portland State University created Indigenous Nations Studies and the American Indian Teacher Program and the Native American Student & Community Center, where groups such as the United Indian Students in Higher Education (UISHE) continue to gather. Rudy Soto (Shoshone-Bannock) was elected the first Native American student body president at PSU in 2008.

Native Americans in Oregon, wherever they live, continue to experience stereotyping, microaggressions, racism, and institutionalized oppression. The Indian community has effectively pushed back through public education and legislative action, and Oregon tribes continue to work with communities to address stereotypical school mascots. In 2017, the Oregon legislature passed Measure SB13, which mandates that the Oregon Department of Education create curriculum on the Native experience in Oregon, including Oregon tribal histories and current events.

Conclusion

The strength of Native people comes from what they bring with them—their sense of culture, community, identity, belonging, and rootedness. Urban Indians stay connected to their cultural identity indirectly by phone, the Internet, social media, and tribal newspapers and directly through traditional ceremonies and intertribal gatherings. As a result, the cultural identity of Urban Indians is fluid and flexible. They maintain a rooted connection to tribal homelands, family, and communities, and Native hubs provide connections that honor tradition and multi-tribal perspectives, resulting in improved and sustainable services. Indigenous stakeholders have made a concerted effort to recreate sacred spaces that honor and provide cultural connections.

Timeline of Federal Indian Policies

Leading with Tradition: Native American Community in the Portland Metropolitan Area

The American Indian Movement (AIM) was founded in 1968 in Minnesota as a policy and civil rights advocacy group. It has been at the center of some of the most significant Native civil. rights actions in the last fifty years, including the occupation of Alcatraz . AIM chapters are active all over the country, including in Portland.

The National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) is a private, non-profit organization based in Portland, Oregon, that has served Native families in the Northwest since the 1980s. In 1992, it expanded its services nationally.

The Native American Youth and Family Center was established in Portland in 1974 as the Native American Youth Association (NAYA) to support the heritage and cultural health and well-being of Native people. It incorporated as the NAYA Family Center in 1994.

Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest (NARA-NW), established in 1970 in Portland, is not only an integrated health services and mental health center managed by and for Native Americans--it also provides substance abuse and social services.

Legislative Commission on Indian Services (LCIS Oregon) was created by statute in 1975 to improve services to Indians in state government and is represented by 13 members representing the Nine Tribes of Oregon (Conf Grand Ronde Tribes, Burns Paiute Tribe, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe, Coquille Tribe, Conf Siletz Tribes, Klamath Tribes, Conf Umatilla Tribes and Conf Warm Springs Tribes), four legislative members and an additional member from the community

-

![]()

Young women from Chemawa trained at the Eugene National Youth Administration for skilled work in the Portland shipyards, 1942.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 013610

-

![]()

Mike Hunter attends the PSU salmon bake with the United Indian Students of Higher Education, 1978.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 1851

-

![]()

Protesting members of AIM take over the BPA office in Portland, 1975.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN022653

-

![Students from PSU, Portland Community College, and Mt. Hood Community College attended.]()

A salmon bake by the United Indian Students of Higher Education, 1975.

Students from PSU, Portland Community College, and Mt. Hood Community College attended. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 1851

-

![]()

Salmon bake at Portland State University, organized by the United Indian Students of Higher Education, 1977.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, photo file 1851

-

![]()

Kathryn Jones (Harrison), far left, speaks at a restoration hearing for the Grand Ronde, 1983.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba0186673

-

![]()

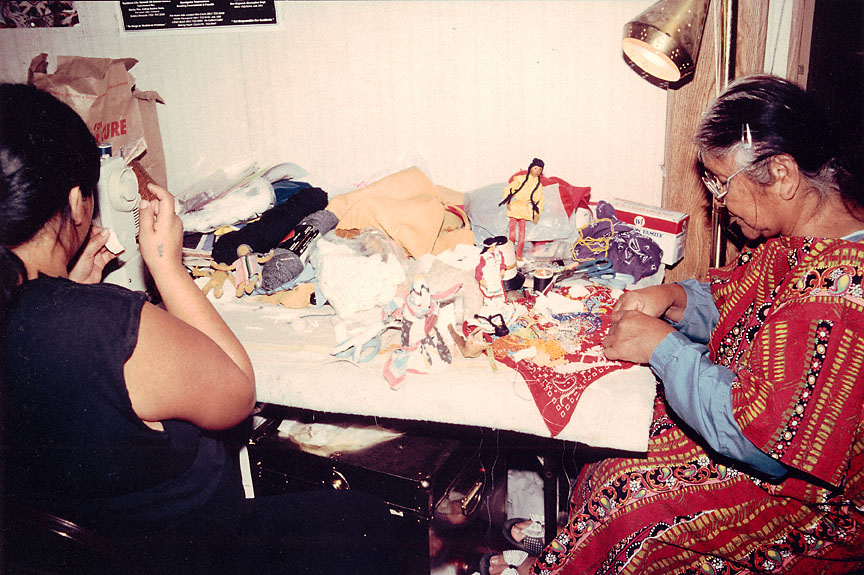

Mary Ann Meanus (Wasco) teaches Rhonda Arthur (on left) traditional doll-making, 1991.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Folklife, P2-41

Related Entries

-

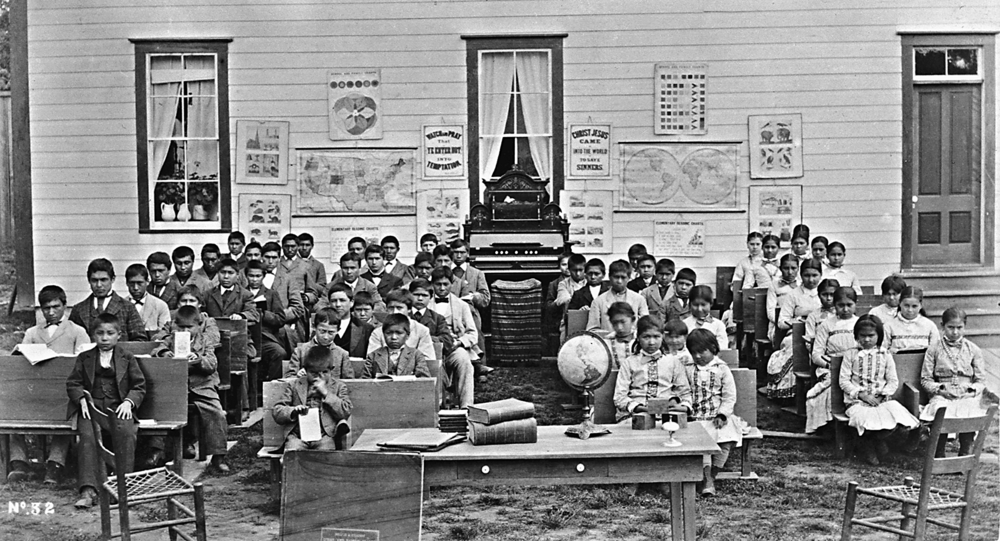

![Chemawa Indian School]()

Chemawa Indian School

Chemawa Indian School, located in the mid-Willamette Valley north of Sa…

-

Indian Boarding Schools

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, only one Indian boarding …

-

![Kaiser Shipyards]()

Kaiser Shipyards

During World War II, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser established three sh…

-

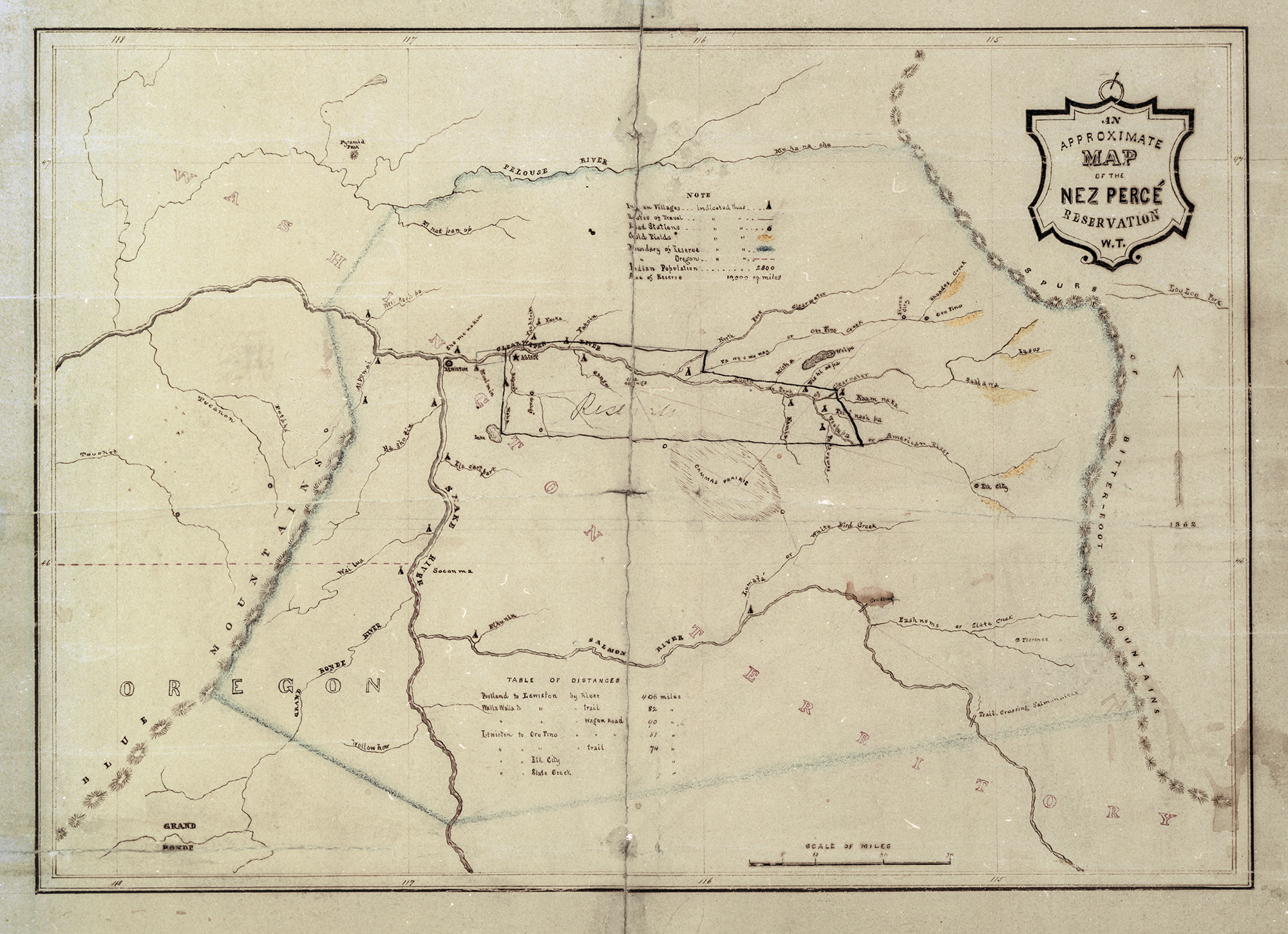

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Termination and Restoration in Oregon]()

Termination and Restoration in Oregon

Termination Of the federal-Indian policies introduced to American Indi…

-

![Vanport]()

Vanport

In its short history, from 1942 to 1948, Vanport was the nation’s large…

-

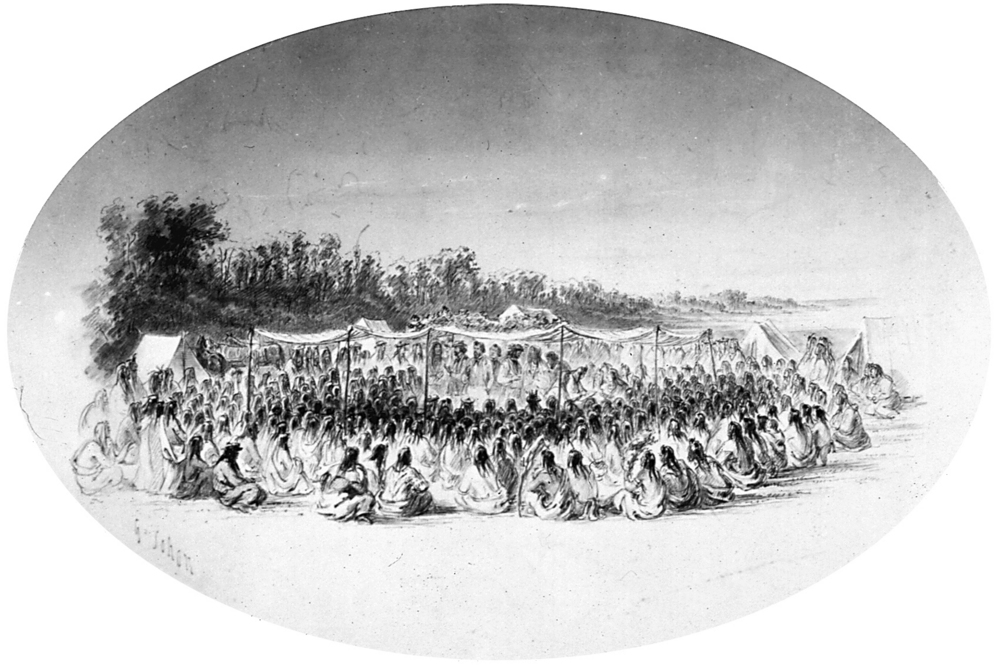

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Wentz-Graff, Kristyna. "Dedication ceremony for artwork at Tilikum Crossing." Oregonian, April 17, 2015.

Ramirez, Renta K. Native Hubs: Culture, Community, and Belonging in Silicon Valley and Beyond. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2007.

Clifford, James. Returns:Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Making the Invisible Visible: A Policy Bluepront for Urban Indian America. Seattle, Wash.: National Urban Indian Family Coalition (NUIFC), 2018

"Report on the Urban Indian in Portland." City Club of Portland Bulletin 56.22 (October 27, 1975).

LaPier, Rosalyn R., and David R.M. Beck. City Indian: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893-1934. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Geiling, Natasha. "How Oregon's Second Largest City Vanished in a Day." Smithsonian.com, February 18, 2015.