The name Molalla ([moˈlɑlə, ˈmolɑlə], usually spelled Molala by anthropologists; also Molale, Molele, Molalis) refers to like-speaking Indigenous peoples who at the time of their earliest encounters with EuroAmerican occupied the greater part of the Cascade Range in Oregon, from Mount Hood on the north to Mount McLoughlin on the south. The name owes its historical currency to a Chinookan name of obscure origin, recorded in the forms [muˈlɑlɪʃ] and [ˈmolɑlɪʃ].

The best documented aspect of Molalla culture is the language through which it was transmitted. From the mid-nineteenth century into the twentieth, a succession of scholars transcribed samples of spoken Molalla from a people known to anthropologists as the Northern Molalla and known to themselves as the Latiwi [ˈlɑ:ti:wi] or Lati-ayfk [ˈlɑ:tiˈʔɑifq] ([−ʔɑifq] ‘people’). Molalla was formerly classified as part of the so-called Waiilatpuan language family, together with the very poorly attested Old Cayuse language (the language spoken by the Cayuse people of northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington in the early nineteenth century before they adopted the neighboring Nez Perce language). Linguists have since concluded that the evidence does not justify such a classification and that Molalla is an isolated language, although one that shows indications of remote common ancestry with other languages of the same region, especially with the neighboring Sahaptian (Sahaptin and Nez Perce) and Klamath languages.

Molalla also shares a good deal of vocabulary with Sahaptin and Klamath, as well as some with Old Cayuse. These consist mostly of words borrowed in one direction or the other, indicative of historical encounters between speakers of all these languages. By the early nineteenth century, Molallas had become extensively intermarried, particularly with Klamaths. The Molalla peoples of the south, known in English as the Southern Molalla or the Eugene Molalla and in Northern Molalla as the Tulenyangsi ([tuˈlænjɑŋsi] ‘far-off people’), had reportedly adopted the Klamath language in addition to or in preference to Molalla. The Klamaths knew their southern Molalla neighbors as the Chakankni [tʃɑkɢæ:nkni:], literally the 'serviceberry-place people'.

While traveling among Chinookans on the lower Columbia River in 1805–1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark learned of “Shoshone” peoples (their term for people of inland cultural type) to the south, including some three thousand who reportedly wintered on the Multnomah River (later named the Willamette River) while ranging across the Cascades for summer fishing, notably on the Towarnehiooks River (today’s Deschutes River). The location and seasonal movement pattern suggests that these people either were Molallas or included Molallas. According to later descriptions, most Molallas wintered in sheltered locations in the western foothills of the Cascades while ranging east into the high Cascades during summer.

Traditional Culture

All sources agree that Molallas subsisted primarily on game, especially deer and elk, supplemented by aquatic and vegetable resources that included salmon and steelhead in mountain streams, camas and hazelnuts on prairies and savannas in the west, and prized mountain huckleberries in the high Cascades. Game provided fur, feather, and hide for clothing and regalia, as well as meat. Huckleberries were either dried whole or processed into cakelike loaves, which along with venison and dressed deer and elk hides, were important Molalla contributions to regional intertribal exchanges of foods and valuables. The Chinookan village-complex at Willamette Falls was one place where such exchanges customarily took place.

The Northern Molalla winter house was similar in type to that described for neighboring Kalapuyans and lower Willamette Chinookans. The walls and roof consisted of slablike strips of dried cedar or hemlock bark lashed vertically to a gabled pole framework. The interior was semi-excavated and furnished with mats and hides. Dirt banking was added outside. Inside was a central square firepit, and sloping ramps led down from doors at either end of the house. Smoke holes with movable bark covers were on both sides of the roof peak. A winter village had one or more such houses occupied by one or more related extended families.

Political organization was minimal, and leadership was task-oriented. Male and female roles were differentiated, with basket weaving, hide dressing, and the harvest of vegetable resources falling mainly to women and hunting and warfare mainly to men. Disease was thought to be caused usually by small intruding objects that could be detected and removed by a traditional healer (shaman), a man or a woman whose power to cure was achieved through prolonged training and a special relationship with the spirit world. Spirits conferred other powers, too, such as skill in hunting or warfare, and they were deliberately sought by youngsters on nightlong quests at isolated places. Such quests may have been considered more important for boys than for girls.

Molallas devoted considerable ceremonial attention to a girl’s coming of age, a cultural preoccupation that set them apart from neighboring Kalapuyans and Chinookans. In common with Klamaths, with whom they were much intermarried, Molallas greeted a girl’s first menses with five-night dances. Ceremonial specialists, holding long poles from which were hung strings of rattling deer dewclaws, kept time and sang, while the girl repeatedly ran forward then danced slowly backward along a short path. The girl’s headband bore painted wood “horns,” with long shell-adorned strings terminating in deer dewclaws that struck her heels as she danced. During the day, she slept outside or in a separate shelter if it was winter. An attending matron lectured her, and she was subject to numerous restrictions—for example, she could not scratch herself except with a bone scratcher. At the conclusion of the ceremony, she was considered marriageable.

A chief was the wealthiest man of a local kin group. He derived his influence in part through ownership of slaves who, as elsewhere in western Oregon, lived in their masters’ households, where they were regarded and treated more or less as poor relations. Free female infants might be subjected to frontal-occipital flattening, an indication that Molallas valued marriage alliances with Chinookans and Klamaths, who associated flat-headedness with free birth.

History Following Encounters with EuroAmericans

Commencing with the establishment of Fort Astor (modern Astoria) in 1811, EuroAmerican traders began to exert influence on regional Native societies. The fur trade led to a general intensification of regional trading activity, including the Indigenous trade in slaves. Slaves originated either as war captives or by purchase from tribes that customarily sold poor children into slavery. The status was hereditary, with the exception that some peoples, including the Molallas, granted free status to slave women upon marriage to free men. The region’s most active early nineteenth-century slave traders were the Klamaths, who used their family ties to Molallas to facilitate their access to the Willamette Valley, where they traded slaves to early Canadian and American settlers as well as to local slave-owning tribes. The settlers acquired Indigenous slaves as farm or domestic laborers, while the Klamaths preferred horses in exchange.

The Molalla-Klamath relationship was a key factor in the lead-up to the most serious recorded clash involving Molallas and American settlers—the Battle of the Abiqua in March 1848. In that obscure and still controversial episode, local American settlers attacked a group of Molallas and Klamaths encamped where Abiqua Creek emerges from the foothills of the Cascades (near the modern communities of Scotts Mills and Silverton), killing an undetermined number of Natives. The settlers reportedly targeted the visiting Klamaths in particular, thereby hoping to reduce what they perceived as an alarmingly large concentration of armed Natives encamped near their new homes. Among the reasons given for the attack were claims that the Natives had intimidated and harassed isolated settler families. There were also reports that Cayuse emissaries were at the Abiqua encampment, posing the possibility that a plot was afoot to enlist local Natives in the Cayuse War, then taking place to the east of the Cascades.

The latter conspiracy theory is expanded upon in a 1934 account attributed to Dee Wright, born in the town of Molalla in 1872 and well known locally as an outdoorsman, Forest Service packer, and raconteur. According to Wright, a Molalla chief named Crooked Finger was trying to raise a multi-tribal force against the Willamette Valley settlements, only to have his plans thwarted by the settlers’ attack, which Wright alleged included a massacre of women and children. Suspicions that there was a massacre formed part of the motivation for some participants to publish their own accounts in local newspapers. While granting that one or a few Indian women were killed while fighting alongside the men, participants denied that there was a massacre.

What has been missing from the discussion is a full account from the Native side. Only one nineteenth-century commentator, pioneer newspaper man Samuel A. Clarke, cites information from a Native source, identified as Mrs. Joseph Hutchins (also spelled Hudson; Molala name: Sanyef [sɑnˈjɛ:f]) of the Grand Ronde Reservation. Sanyef was a daughter of Kootsta [ˈku:ts.tɑ], the principal Molalla chief involved in the incident, and her mother was Klamath. Clarke acknowledges her claim “that many of these eighty Klamaths [encamped at Abiqua Creek] were her mother’s family connexion [sic], and merely came on a friendly visit to their kindred.” It is unfortunate that Clarke devoted the balance of his account to a verbose justification of the settlers’ attack—writing that it “showed promptness and bravery on the part of the whites, and was important in its consequences by teaching the natives the power and manhood of the settlers,” for example—rather than providing more information from the other side, to which he (evidently alone) had managed to find direct access. He recounts only one anecdote from Sanyef: an Indian crossing a foot-log bridge, whom the settlers believed they had shot and to whom they attributed a red blanket seen floating downstream, was not killed but floated downstream and emerged from the water. This anecdote may be connected to claims by some settlers that a Klamath chief named Red Blanket was killed in the fray.

The only other Molalla account referring to armed conflict between Molallas and settlers appears in a Molalla narrative text dictated in 1911 by Stevens Savage (Molalla name: Pathlilh [ˈp’ɑ:ɬɪɬ]) to the linguist Leo J. Frachtenberg. This narrative bespeaks a Molalla reworking of history, in which an evidently faded memory of the Abiqua engagement is woven into a larger account of Native-settler conflict and negotiation. In this telling, “General Palmer” (Superintendent Joel Palmer, who was not a serving military officer but who did negotiate treaties with Oregon tribes in the 1850s) brings soldiers to Molalla country, demanding that the Molallas submit to removal to a reservation. Two friendly settlers named Whitlock and Woodcock advise the Molallas not to give up their land. Whitlock serves as an intermediary between the Molallas and Palmer, relaying the message to Palmer that the Molallas have decided to fight rather than give up their land. Warning Whitlock and Woodcock to stay clear, the Molallas fight the soldiers for a half-day, after which Palmer agrees to pay the Molallas $46,000 for their land. The name Whitlock matches that of Mitchell Whitlock, known to be a participant in the Abiqua affair. Possibly, the name Woodcock was misremembered (or misheard by Frachtenberg) for that of another participant, John Warnock, who according to Warnock family tradition acted as an intermediary between the two sides in that engagement.

While there is no confirmation from the Molalla side of there having been a massacre at Abiqua Creek, disruption caused by the incident may help explain why documents accompanying the ratified treaties of 1854 and 1855 show a gap between the northern and southern areas of Molalla occupancy. The earlier unratified Champoeg Treaty of 1851 clearly shows a Molalla claim to that central zone. That treaty shows a population of 121 Molallas in 1851, excluding Southern Molallas. Most of these Molallas were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation. In 1881, 55 Molallas, presumably Southern Molallas, were counted among residents of the Klamath Reservation.

The Reservation Era

It is to a handful of Molallas of the reservation era that we owe most of our record of the Molalla language and culture. The most significant single source consists of Frachtenberg's unpublished collection of Molalla-language dictations from Stevens Savage, transcribed with field translations in 1910–1911. Savage had long been associated with the Grand Ronde Reservation, but was then residing at the Siletz Reservation, where his cousin Kate Chantelle (Molalla name: Muswi [ˈmuswi]) had relocated. Kate Chantelle dictated Molalla-language narratives to Melville Jacobs of the University of Washington in 1928; and in 1934 she provided ethnographic information in English to anthropologist Philip Drucker. While Chantelle's Molalla-language narratives consist entirely of untranslated phonetic transcripts, recent progress in deciphering the language promises finally to reveal their contents.

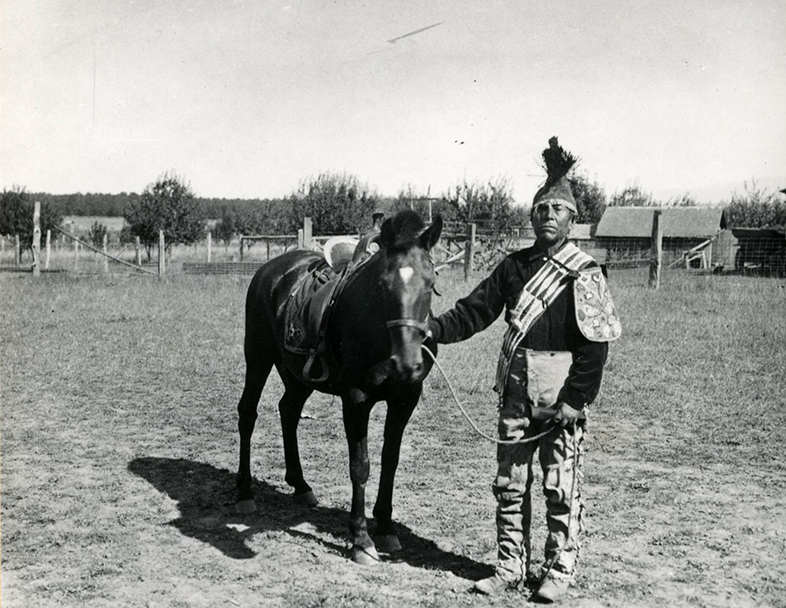

Some Molallas established themselves apart from any reservation. Henry Yelkes, son of the Northern Molalla treaty chief Yelkas [ˈjɛlqɑs], was well known to settlers in and around the town of Molalla. He was also the source of a Molalla vocabulary appearing in volume 8 of Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian; and he was the father of Fred Yelkes Sr., who provided linguistic data to Jacobs. Fred Yelkes Sr. lived until 1958 and was the last person known to have spoken Molalla from childhood.

The rolls of the contemporary Grand Ronde, Siletz, Klamath, Warm Springs, Cow Creek, and Yakama tribal communities include individuals of Molalla ancestry. Not all Molalla descendants are to be found there; others live independently of any tribal community.

-

![]()

Henry Yelkus, 1912.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Drake Bros. Studio, Orhi46975

-

![]()

Molalla Kate Chantal in traditional dress..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi65285

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1856, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)]()

Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)

According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with …

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Elizabeth Jacobs (1903-1983)]()

Elizabeth Jacobs (1903-1983)

Elizabeth D. Jacobs’s fieldwork with the Nehalem Tillamook and southwes…

-

![Henry Yelkus (c. 1843–1913)]()

Henry Yelkus (c. 1843–1913)

Henry Yelkus (also spelled Yalkus, Yelkes, Yelkis, Yal-kus, and Yelcus)…

-

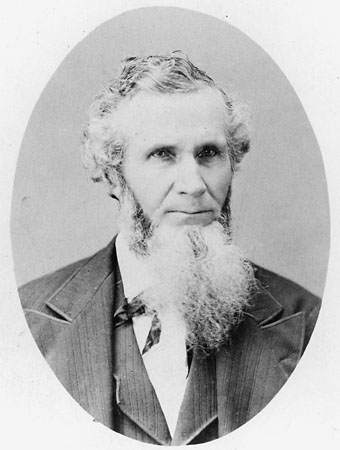

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)]()

Melville Jacobs (1902-1971)

Melville Jacobs did more to document the languages, cultures, oral trad…

-

![Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)]()

Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)

Molala Kate Chantal (also known as Molala Kate)—the daughter of Molalla…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Berman, Howard. "The Position of Molala in Plateau Penutian." International Journal of American Linguistics 62, no. 1 (1996): 1–30.

Brekas, Jeff. “Aumsville Historian Compiles ‘Warnock Family Notes.'” Silverton Appeal.com, April 13, 2005.

Clarke, Samuel A. "Battle of the Abiqua: A Story Never before Fully Told." Sunday Oregonian, September 6, 1885.

“Dee Wright Dies Here on Tuesday.” Eugene Register Guard, April 24, 1934.

Down, Robert Horace. A History of the Silverton Country. Portland, OR: The Berncliff Press, 1926.

Frachtenberg, Leo J. “Molalla Texts and Grammatical and Ethnological Notes, 1910–1911. Mss. 2517, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Olson, June. Living in the Great Circle: The Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, 1855–1905. A. Menard Publications, 2011.

Pharris, Nicholas J. “Winuunsi Tm Talapaas: A Grammar of the Molalla Language.” Ph.D. diss, University of Michigan, 2006.

Rigsby, Bruce. "The Waiilatpuan Problem: More on Cayuse-Molala Relatability." Northwest Anthropological Research Notes 3, no. 1 (1969): 68-146.

Vernon, Stivers. "Saga of the Molalla Hills." Sunday Oregonian, magazine, Pt. 1, April 29, 1934; Pt. 2, May 5, 1934.

Zenk, Henry, and Bruce Rigsby. "Molala." In Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 12: Plateau, ed. Deward Walker and William C. Sturtevant, 439-445. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1998.