The Pioneer Period, 1850-1860

The Cantonese-Chinese were the first Chinese in Oregon. They immigrated to America primarily from the Pearl River Delta region in southeast China in the century from 1850 to 1960. This region forms the central third of their home province of Gwongdung (Cantonese pronunciation; Guangdong is the standard Pinyin "Mandarin" Chinese spelling, formerly spelled in Wade-Giles Mandarin as Kwangtung.) This group decisively shaped the first century of Chinese experience in Oregon.

Small groups of Cantonese-Chinese miners, who arrived in Oregon Territory in 1850-1853, represented the first Chinese migration beyond northern California, the earliest and primary location of Cantonese-Chinese settlement in America (1850-1860). In the early 1850s, these miners and a handful of merchants settled in two different but widely separated parts of Oregon Territory.

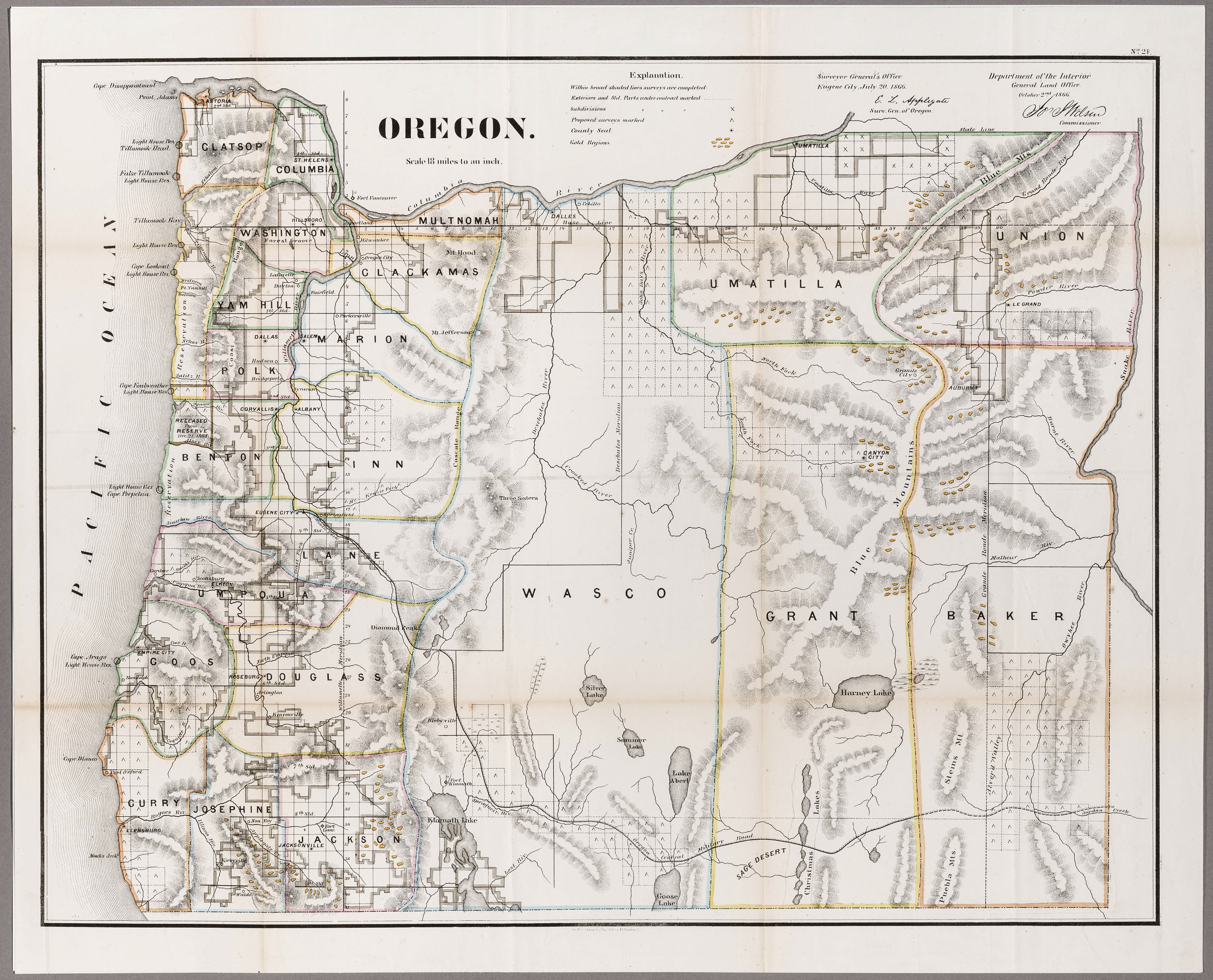

They went first to southwest Oregon, with the largest number settling in Josephine and Jackson Counties; fewer went to Douglas and Grant Counties. These Chinese formed a geographical and chronological extension of Cantonese-Chinese mining activity in northern California’s Shasta and Trinity Counties. The second location was in northeast Oregon, which became the gateway to the Inland Empire in the southeast corner of Washington Territory (1859-1889), with specific reference to Walla Walla and the Boise Basin in present-day Idaho (1863-1890).

From 1855 through 1865, the majority of Cantonese-Chinese settlers in Oregon were miners, with a minority of merchant types. Their numbers were unstable, rising and falling with the boom and bust of gold mining. The 1860 census officially lists thirteen Chinese in all of Oregon, with ten of them in Benton County. Given the unstable material conditions of the time and the general reports of locals, it is safe to surmise that this number represents a serious undercounting. It is more accurate to say that there was a likely range of from a few dozen to a few hundred Cantonese-Chinese in Oregon, especially in the early 1860s.

The Cantonese-Chinese presence is best characterized as that of a pioneer community, which embraced a small population of highly mobile miners and merchants who moved about in response to opportunities to mine for gold or to "mine the miners" (both Chinese and white). Conditions were not conducive for the formation of permanent ethnic Cantonese-Chinese communities in Oregon.

Continuous migrations of single young men, however, did not require permanently structured communities. There were no Chinese women as wives and mothers—just a few prostitutes and slave girls—and certainly no Chinese families. After the mid-1860s, Cantonese-Chinese settlement in Oregon underwent a major transformation, characterized by accelerated population growth, geoterritorial expansion, and the establishment of permanent ethnic Cantonese-Chinese communities.

The Sojourner Period, 1860-1885

The heyday of nineteenth-century Cantonese-Chinese settlement in Oregon occurred from 1860 to 1885. Changing material conditions in Oregon and elsewhere in the American West opened up economic opportunities that attracted increasing numbers of Cantonese-Chinese from California and directly from Gwongdung. Major factors included (1) new and more diverse economic opportunities; (2) accelerated Chinese demographic growth; (3) urbanization, chiefly in the Portland area; (4) sociopolitical bifurcation—that is, communal leadership by a minority of merchant elites, with a demographically larger but sociopolitically subordinate mass of laborers; (5) institutional development by way of establishing community-wide social organizations with overlapping political, economic, and sociocultural functions; and (6) the anti-Chinese movement in the American West, including Oregon.

Between 1860 and 1870, new and diverse economic developments occurred in the West, specifically in Oregon. Precious metals increasingly lost their allure as a quick and easy way to get rich, and there was a shift away from mining activities. Some Chinese and non-Chinese miners followed gold and silver strikes elsewhere and moved to other locations in the American and Canadian West to mine. Others abandoned their roles as prospectors and took jobs working for corporate mining enterprises. For example, Chinese were hired by white-owned hydraulic-mining companies to dig ditches, burrow tunnels, and construct bridges and trestles. Underground mining closely associated with corporate mining enterprises undoubtedly figured more prominently elsewhere, especially in California, Nevada, Colorado, and Wyoming.

In addition, increasing numbers of Chinese were more attracted to economic opportunities other than mining. This most often took the form of jobs in commercial agriculture, salmon canneries, railroad construction, domestic service, and service work (e.g., in hand laundries or as cooks in lumber camps and on ranches). This squares well with the general pattern of economic development engineered by white society in Oregon during the same period. Consequently, the shift in the kinds of enterprises that local Chinese merchants became identified with and the kinds of jobs Chinese laborers undertook mirrored the changing economy of Oregon in the later nineteenth century.

These changes motivated scores of Cantonese to seek alternative economic opportunities either as laborers or as small businessmen and entrepreneurs. A minority—those with a small amount of capital—opened cafes, laundries, general stores, and laborer brokerages to serve the needs of Chinese seeking jobs and both Chinese and non-Chinese employers seeking Chinese workers.

The railroads provided especially important benefits for the Chinese in the American West, giving them a source of income and directing Chinese migration throughout the region. The era of transcontinental railroad construction, from 1865 through the 1880s, also stimulated the building of regional spurs. In this way, Cantonese-Chinese not only worked their way across the land, but they also were introduced to new destinations.

In Oregon, Cantonese-Chinese migrated to and settled in eastern Oregon, on the Oregon Coast, and in the Willamette Valley. Commercial agriculture, lumbering, fisheries, and canneries provided jobs for many. Other employment opportunities in white American society included jobs in domestic service (e.g., as cooks, gardeners, houseboys, and nannies), light manufacturing, truck gardening, hand laundries, cafes and restaurants, and nurseries.

The number of Chinese in Oregon grew dramatically after the mid-1860s. By 1870, their numbers were distributed unevenly across southwest Oregon, especially in Josephine and Jackson Counties; the central Willamette Valley, in Lane, Benton, Linn, and Marion Counties and some in Polk and Yamhill Counties; the northern Willamette Valley, in Multnomah, Clackamas, and Washington Counties; in northwest Oregon, in Clatsop and Columbia Counties; and on the Columbia Plateau, in Wasco, Umatilla, and Union Counties, with some Chinese also in parts of Baker, Wallowa, Morrow, and Grant Counties. The number of Chinese in Oregon rose steadily from 3,330 in 1870, to 9,510 in 1880, to 9,540 in 1890, cresting at 10,397 in 1900. Few Chinese lived in the northern and central Cascades, in the southeast corner of the state as part of the Great Basin, and on the coast from Tillamook south to Coos Bay.

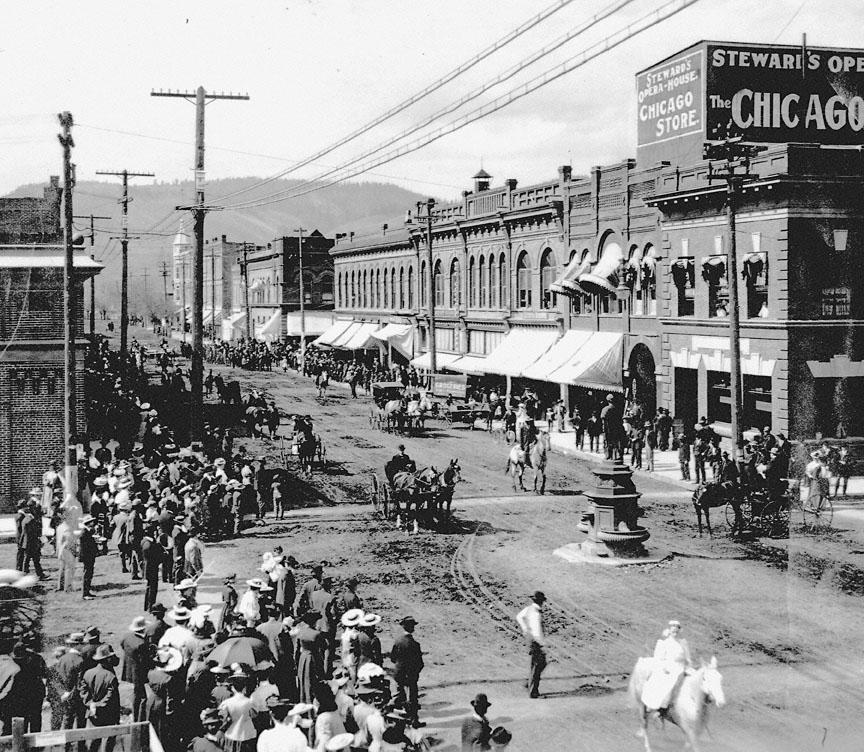

The most notable change in the resident Cantonese-Chinese population in Oregon during 1870-1885 occurred in Portland, where 22 Chinese lived in 1860, 200 in 1865, 500 in 1869, and 720 in 1870. By 1880, there were about 2,480 in the city. This accelerated population growth and high-density concentration were the result of the confluence of timely developments. Strategically located between the Columbia and Willamette Rivers, Portland served as a transportation and communications hub and a financial center not only for Oregon but also for much of the Pacific Northwest before Seattle eclipsed it after 1885. Not only the dominant white society, but also the Cantonese-Chinese minority benefitted from Portland's attractions and advantages. With the largest Chinese community between San Francisco and Vancouver, B.C., the city not only housed an increasingly large and stable ethnic Cantonese-Chinese community, but it also served as a key routing center for the migration of Cantonese workers across the Pacific Northwest.

From 1860 to 1885, thousands of Cantonese-Chinese immigrants effectively transitioned from transient migratory pioneers, constantly on the move and anticipating a quick return home to China, to longtime resident sojourners. There remained the expectation of return home; but as years stretched into decades, increasing numbers of Cantonese pioneers settled into structured and permanent ethnic communities, such as the one in Portland.

As resident Chinese communities became larger and more permanent, social tensions emerged. This contributed to a bifurcation of Cantonese sojourner society into two social classes. At the top was a numerically smaller but socially prominent, economically prosperous, and politically well-leveraged class of businessmen, merchants, and entrepreneurs. They provided jobs and loans and dominated social life through community organizations, which they led. They also directed the flow of social services and philanthropic activities. The only other social class consisted of laborers, who were generally poor, socially disadvantaged, and politically weak. They formed the majority of Cantonese-Chinese ethnic communities.

Both classes engaged in and were alternately helped and harmed by communal conflicts. These conflicts could be social and cultural in nature—for example, based on subethnic factors or speech-community divisions, including Say-Yup Cantonese (four districts, southwest of Canton) versus Sam-Yup Cantonese (three districts, immediately adjacent to Canton), or the Hakka (settlers in Gwongdung after 1000 CE) versus the Bundae ("Natives," or settlers in Gwongdung before 1000 CE).

Conflicts also could be political, including turf wars between rival clan (or family) associations, district (or native place) associations, and secret societies (or Tongs). After 1890, political conflict also involved nascent political parties and advocacy groups. Portland's Chinese community, for example, had local chapters of the Pao Huang Hui (Protect Emperor Society, commonly known as the Chinese Empire Reform Association) and the T'ung Men-hui (Revolutionary United League). In addition, local Chinese Christians and the local Chinese Chamber of Commerce were active advocacy groups.

In the more than half-century between 1855 and 1940, Cantonese-Chinese Portland was organized much like Cantonese San Francisco and other major Chinese communities in North America. Merchants helped establish social organizations that came to exercise political control over the community's civic and social life. They did so by monopolizing the leadership of key organizations, including (1) lineage, clan, or family associations, organized on the basis of commonly shared surnames; (2) the wooi-kun, commonly known as district associations or "native place" organizations, where membership revolved around identification with a Chinese district or group of districts (much like counties); (3) guilds and other professional groups; (4) secret societies in the form of large fraternal lodges or smaller "fighting tongs"; and (5) Chinese Christians and community independents.

These organizations provided a complex web of affiliation, which embraced both benefits and liabilities. Individually and collectively, they provided social service benefits, including loans, medical and legal help, a place to stay, job referrals, and protection. They also stimulated and expanded intracommunal rivalries and conflicts between community organizations. Consequently, community life was both complex and problematic. The rise of fighting tongs and their monopoly of the vice trades—prostitution, opium, gambling, and smuggling—contributed to violent conflicts.

Portland's Chinese community not only had its own local tensions, but its members also became embroiled in conflicts that spilled over from San Francisco and elsewhere. In this way, the city provided a safe haven from anti-Chinese harassment and violence, but it also harbored its own challenges to the personal security and material wellbeing of its residents.

From 1870 to 1885, a rapid acceleration and expansion of the anti-Chinese movement took place in Oregon, paralleling similar developments elsewhere in the American West. A decade earlier, a nascent anti-Chinese movement in the state had produced isolated instances of ridicule and harassment, and local anti-Chinese ordinances had been designed to put the Chinese in their place, as outsiders. In the 1870s, the movement gained strength as state labor and political leaders called for both the expulsion of Chinese residents and the exclusion of future Chinese from Oregon.

As late as the mid-1880s, expulsion efforts included the burning of two large buildings in Portland's Chinatown and the raid by eighty masked men on Chinese woodcutters' camps near Albina, with the Chinese there being shipped to Portland. The anti-Chinese club in Portland sponsored rallies with speeches, fundraising, brass bands, and dancing. In 1885, about five hundred Chinese were ejected from Tacoma, Washington, and many were sent by rail to Portland, creating further tensions in the city.

The most notorious incident occurred in 1887, when a small group of white men massacred thirty-four Chinese miners in Hells Canyon in Wallowa County. The injury and ejection of Chinese in Oregon and throughout the West helped usher in Chinese exclusion.

The Exclusion Period, 1885-1940

In 1878, the Page Act banned the immigration of Chinese women of "immoral character"—that is, those considered to be prostitutes. The law, both substantively and procedurally, set the pattern for discriminatory federal policies and laws designed to ban Chinese immigration to the United States. As the first federal law to target Chinese, the Page Act established a presumption of liability that required a person so accused to overcome the presumption with evidentiary proof. Thus, women were presumed to be "immoral" and, therefore, deportable until they could prove otherwise.

In 1882, Congress passed the first federal Chinese Exclusion Act, which specifically banned the entry of Chinese laborers to the United States for ten years. As a practical matter, the law banned the entry of nearly all Chinese, even though Chinese merchants, diplomats, professionals, and students were exempt. Under the law, there existed the presumption that every Chinese immigrant seeking entry into the United States was a member of the banned class of laborers, until he could prove otherwise. In 1892, the Geary Act renewed Chinese exclusion for an additional ten years and required every Chinese to carry photo identification. In 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Law was renewed and made permanent; it was not repealed until 1943.

In Oregon, the period 1882-1943 is known as the Exclusion Era. During this period, as a practical matter Chinese could not legally enter the United States, and Chinese women were excludable as wives of banned Chinese laborers. Oregon also banned interracial marriage. Cantonese-Chinese men in America had several options: (1) remain celibate; (2) engage prostitutes; or (3) seek out common-law marriages or consensual arrangements with Black, Native American, Hispanic, or white women. During this time, Chinese were ineligible for naturalization on the basis of a 1789 law that limited naturalization to white immigrants. Additionally, Chinese were discriminated against in housing; banned from attending public schools, entering professions, and serving on juries; and not allowed to vote or hold office.

Without the possibility of new generations of Chinese, either by immigration or by birth, the Cantonese population in Oregon and elsewhere in the United States began to decline. As a result of forced ejection, violence, and federally mandated exclusion, Oregon's Cantonese population declined from about 10,390 in 1900 to 7,363 in 1910, 3,090 in 1920, 2,075 in 1930, and 2,086 in 1940. The number bottomed out at 2,102 in 1950.

Daily life for Cantonese-Chinese in Oregon was challenging. Most Cantonese lived in Portland, which like Cantonese communities in San Francisco, Vancouver, Oakland, Seattle, Chicago, and New York City had become isolated and insulated. The Chinese in Portland were never walled off and isolated in a ghetto, and they continued to interact with both mainstream white society and other ethnic groups (e.g., African Americans) in Portland and elsewhere. They lived in their own communities, but many also left to work elsewhere. Whites and other non-Chinese often crossed ethnic and racial neighborhood boundaries to conduct business or as visitors and tourists.

During this time, three identifiable Cantonese-Chinese ethnic communities developed in downtown Portland, on the west bank of the Willamette River. The initial Chinese community was bounded by Front and Second Streets and Market and Jefferson Streets. It later expanded to include several square blocks bordered by Front and Third Streets and stretching from Clay to the south and to Ash to the north. A second community, consisting of Cantonese farmers working their vegetable gardens, grew up in the heights overlooking the first area of settlement. This atypical rural community, set within Portland’s increasingly crowded downtown, thrived from 1879 until 1910. It lay west of Fourteenth Street and north of Market. By 1900-1901, the first Cantonese community had expanded north and extended to the other side of Burnside Street. This extension included portions of Second, Third, and Fourth Streets to the north, which became the nucleus for Portland's third Chinatown, which still exists. (In the twenty-first century, a fourth Cantonese Chinese community, which includes ethnic Chinese from Southeast Asia, developed on the east side of the river along the corridor of 82nd Avenue.)

Chinese were not allowed to live in areas beyond their own community, except possibly as live-in domestics. A few men with wives and children formed a small nucleus of Cantonese-Chinese families. Despite the rigors of exclusion, there were a few dozen to a few hundred American-born Cantonese youth in Portland by the 1940s. Because the Chinese in Oregon were racially segregated from whites, children were banned from attending public schools. Chinese also encountered prejudicial discrimination in housing, jobs, commercial opportunities, education, and medical and social services. Over time, the Cantonese-Chinese community in Oregon became almost invisible on both the rural and urban landscape.

The Cultural Assimilation Period, 1940-1960

If exclusion and the Great Depression made daily life difficult for the Chinese in Oregon, World War II and the end of exclusion reversed things. The older sojourner generation declined, as many retired, returned to China, or died. Oregon's increasing numbers of Chinese were either American-born Chinese (ABC), whose numbers increased dramatically between 1940 and 1970, or emigrants to Oregon from California and elsewhere. These Cantonese-Chinese, as Chinese Americans, were culturally assimilated, having either been born, raised, and educated in America or immigrated (legally and illegally) in their youth. Their experiences and identifications led them to successfully compete in both classrooms and the job market.

Among the foreign-born Cantonese, a significant number had served in the U.S. armed forces during World War II, and as veterans they were allowed to send for or otherwise obtain Cantonese-Chinese wives. Scores of Chinese in Oregon began to relocate beyond Portland’s Chinatown, living and working in mainstream white society. In Portland and other urban communities, these Chinese were viewed in a positive way. They worked hard and were friendly, law-abiding citizens who paid their taxes and did not get involved in anti-social behavior (e.g., their children were well behaved and excellent students). They also spoke English well and had nice homes and cars. In this way, the Chinese in Oregon transitioned from being viewed as undesirable foreigners to admired fellow Americans.

After World War II, the Cantonese-Chinese, along with American-born Japanese and Korean Americans, became known as "model minorities." Members of all three groups experienced a rapid and smooth cultural assimilation in classrooms, at home, and on the job. Scores went to college, and many became physicians, lawyers, architects, engineers, educators, social workers, scientists, and other professionals.

The subtext of this effort, however, was motivated by the same racism that Asian immigrants and Asian Americans have always endured. The pressure to be an "ideal American citizen"--a notion vaguely and arbitrarily defined by whites--carried with it threats of economic and cultural discrimination, exclusion from legal protections, and violence. Under those circumstances, assimilation can be traumatic, and cultural groups have worked to maintain cultural identies in recognition of the effects of race-based discrimination and loss.

In 1943, by executive order, President Franklin D. Roosevelt repealed the Chinese Exclusion Law. A few years later, in 1952, Congress passed the McCarran-Walter Act, which provided that only 105 Chinese could immigrate to the United States each year. The law, together with the rapid increase in the number of American-born Cantonese-Chinese, significantly changed the demographics of Chinese in Oregon. From 1945 into the 1960s, most Chinese in Oregon, and elsewhere in America, were born, raised, and educated in the United States. For the first time, foreign-born Chinese formed a small minority of Chinese in Oregon. The vast majority lived in urban and suburban communities.

Portland's Chinatown, as Oregon's oldest and largest ethnic Cantonese-Chinese community, experienced dramatic change. Geographically and demographically, its boundaries, businesses, and residents declined, as increasing numbers of Chinese worked and lived outside Chinatown. Chinatowns in Washington, D.C., Oakland, Seattle, Boston, Chicago, and Honolulu experienced similar changes. The era of the "model minority" brought an accelerated cultural assimilation of American-born Chinese Americans and an accelerated decline of those born in China. This process was abruptly reversed after 1965.

Chinese American Renaissance in Oregon, 1960-2000

With the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act, more commonly known among Asian Americans as the Pan Asian Immigration Law, greater numbers of Chinese emigrated to the United States from more diverse parts of the Chinese-speaking world. By 1968, the Chinese had begun to fully subscribe their allotted quota of 20,000 immigrants per year. That number, however, did not include individuals seeking reunification with their families. When they are included, the quota was actually about 100,000 per year.

After 1968, most of the 100,000 Chinese who entered the United States each year settled in California, New York, and elsewhere. Consequently, between 1968 and 1980, there were about a million new Chinese immigrants in the country. Few settled directly in Oregon, but instead initially settled in California or elsewhere and then some relocated to Oregon. Once a nucleus of these new immigrants settled in Oregon, they sent for members of their extended families. Thus, by the early 1980s, a greater number of Chinese from more diverse places had begun to settle in Oregon, especially in Portland and its suburbs.

After 1980, many Chinese immigrants were not Cantonese, but were Chinese from Taiwan, Burma, Singapore and Malaysia, and Indochina (Vietnamese Chinese, Cambodian Chinese). After the later 1980s, there appeared a growing number of Chinese immigrants from Mainland China. In this way, Min speakers from Fujian, Wu speakers from Shanghai and elsewhere in the lower Yangtze, and Mandarin speakers from northern and southwest China settled in growing numbers in America. These groups are well represented among the Chinese in Oregon since 1990.

Since 1990-2010, many Chinese have emigrated from Latin America and the Caribbean, where they speak Spanish and a variety of Chinese dialects, including Hakka, Hokchiu, Hokkien, and Teochiu (Chaozhou) as well as Cantonese and Mandarin. Consequently, the several thousand Chinese who live in Oregon are diverse ethnically (e.g., Cantonese, Min, Wu, Teochiu, Mandarin, and ABC English speakers), socially (e.g., families, singles, young couples, and seniors), and economically (e.g., lower middle class to upper middle class, professionals, affluent entrepreneurs, and business leaders). Culturally speaking, there are non-English speakers and limited-speakers, and there are highly educated, culturally assimilated, and articulate bilingual speakers.

Geographically, most of Oregon's Chinese live in the Willamette Valley, especially in urban areas such as Portland, Salem, Albany, Corvallis, Eugene, and Medford. Fewer live in central and eastern Oregon and in urban locations on the north coast (Lincoln City and Astoria). As in the past, few Chinese live in the southeast corner of the state, in the Cascades, or along most of the southern coast. The Chinese American community remains historically a socially bifurcated society, divided between the foreign-born and the American-born.

After the 1990s, most Chinese who settled in Oregon could be divided into three groups, based on place of origin, socio-economic standing, and degree of cultural assimilation. First, there are the foreign-born, less affluent, nonlimited English-speakers, who came chiefly from Mainland China, Southeast Asia (chiefly Indo-China), and parts of Latin America and the Caribbean. These immigrants, who came with their families, gravitated to the service sector, working in businesses and markets owned and operated by ethnic Chinese. They tended to congregate in urban areas such as Portland and Salem.

The second group consists of foreign-born Chinese who are better educated, more affluent, and more culturally assimilated and who are typically single, married with no children, or married with small children. These Chinese are chiefly from Hong Kong, Taiwan, or major urban areas of China (Shanghai, Beijing, Chongqing), as well as other major urban locations in Singapore, Malaysia, Australia, Latin America, and the Caribbean. They also tended to settle in urban areas and surrounding communities.

The third group of Chinese to relocate in Oregon after 1990 were the American-born or those Chinese Americans who have lived in the United States for a long time. These Chinese relocated to Oregon because of jobs, schooling, and business. They came primarily from California, Hawaii, the Midwest, and the East Coast, with some from western Canada (Vancouver, B.C.).

By the first decades of the twenty-first century, Oregon's Chinese had become much more diverse in their ethnolinguistic, socioeconomic characteristics and in their settlement patterns. They form one of the largest Asian American subgroups in Oregon. Asian Americans in turn form the second largest and fastest growing minority groups in Oregon, after the Hispanic/Latino population.

-

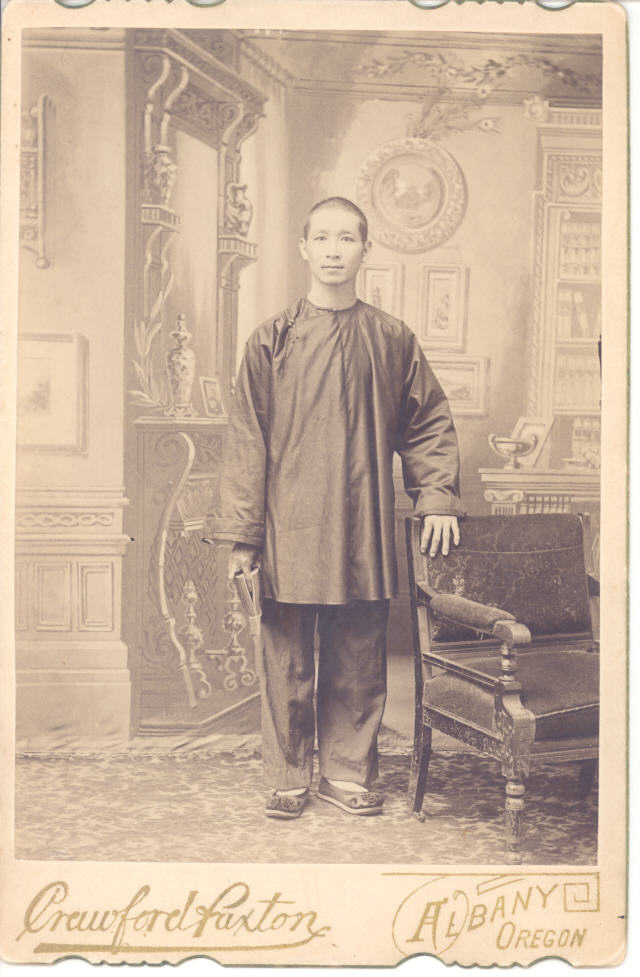

![Unknown resident of Albany, Oregon]()

Unknown resident of Albany, Oregon.

Unknown resident of Albany, Oregon Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

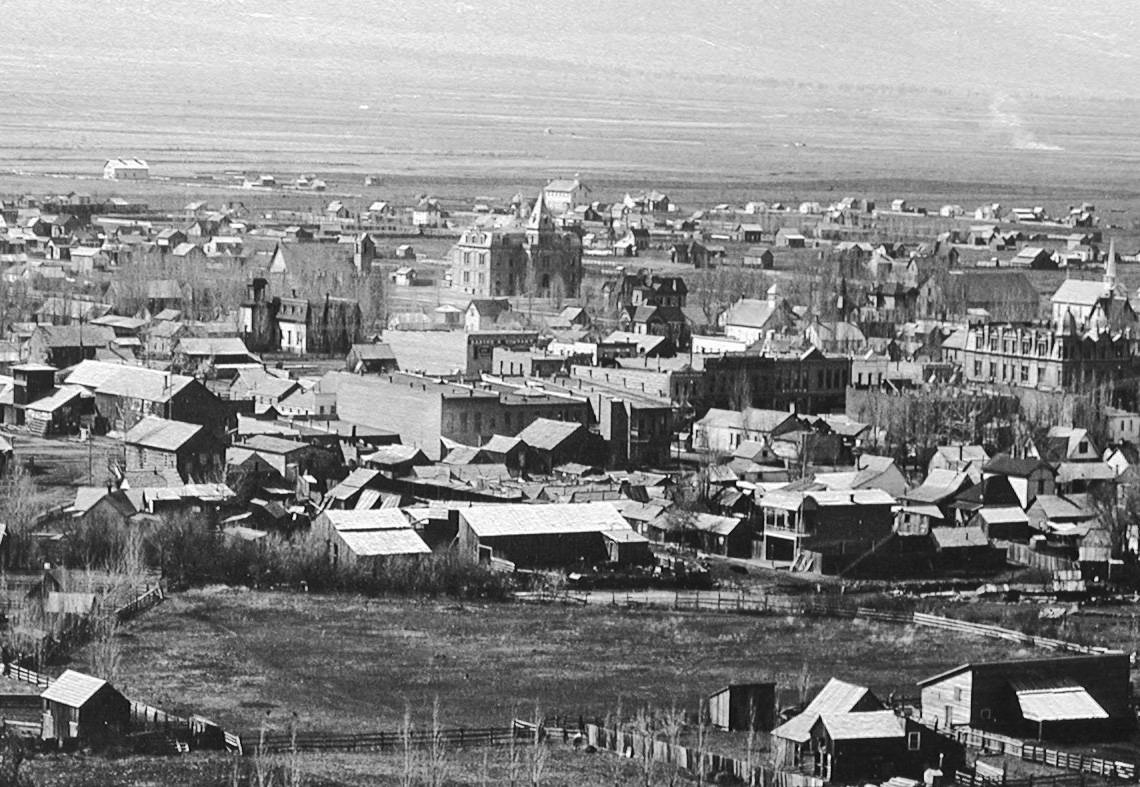

![Millard Chung is identified on the left.]()

Members of the Chinese Flying Club, 1935.

Millard Chung is identified on the left. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 59675

-

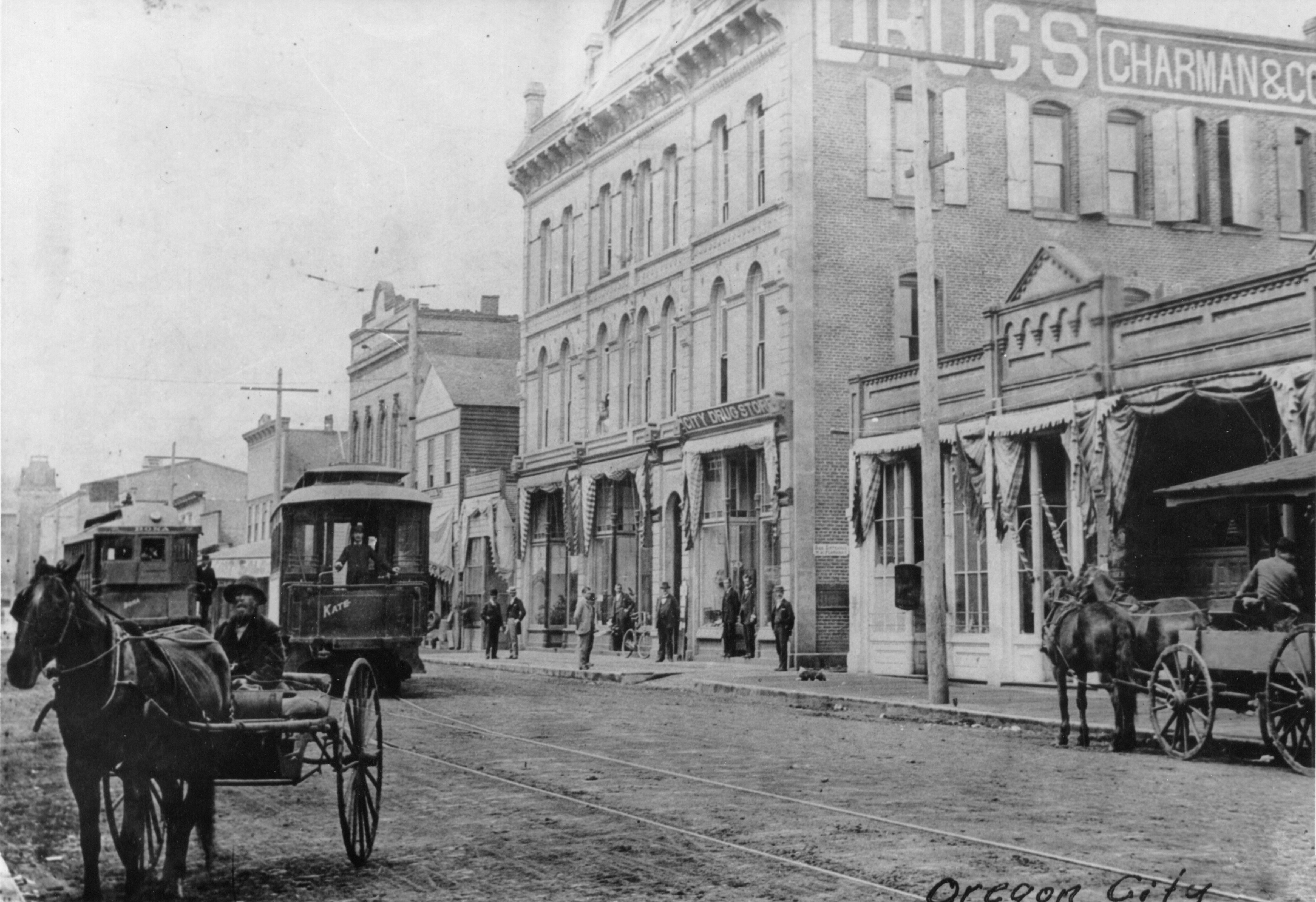

![]()

Lung On, in Baker, Oregon.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 53840

Related Entries

-

![Ah Hee Diggings (Chinese Walls)]()

Ah Hee Diggings (Chinese Walls)

The Ah Hee Diggings, also called the Chinese Walls, are sixty acres of …

-

![Baker City Chinatown]()

Baker City Chinatown

For over seven decades, Baker City had an area referred to as Chinatown…

-

![Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek]()

Chinese Massacre at Deep Creek

Of the many crimes and injustices committed against early Chinese immig…

-

![Edward Wah (1931?-2008)]()

Edward Wah (1931?-2008)

Edward Eng Wah, D.M.D., practiced dentistry in both Portland and John D…

-

Eldorado Ditch

The El Dorado Ditch, also known as the Eldorado and the Big Ditch, was …

-

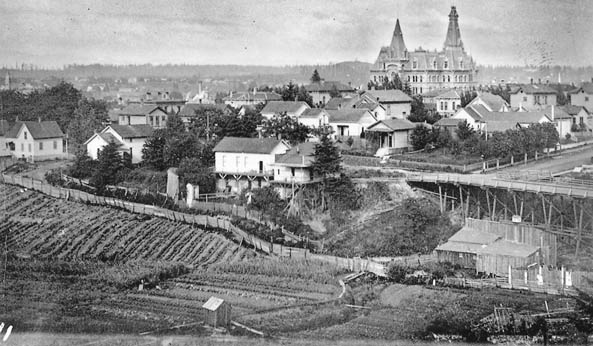

![Expulsion of Chinese from Oregon City, 1886]()

Expulsion of Chinese from Oregon City, 1886

On February 22, 1886, approximately forty men gathered in Oregon City a…

-

![Goose Hollow]()

Goose Hollow

One of the oldest neighborhoods in Portland, Goose Hollow has a history…

-

![Hazel Ying Lee (1912-1944)]()

Hazel Ying Lee (1912-1944)

Hazel Ying Lee, who was born and educated in Oregon, was the first Chin…

-

![Ing Hay ("Doc Hay") (1862-1952)]()

Ing Hay ("Doc Hay") (1862-1952)

Ing Hay (Wu Yunian), also known as Doc Hay, was a partner of Kam Wah Ch…

-

![Kam Wah Chung and Co.]()

Kam Wah Chung and Co.

The Kam Wah Chung and Company (Jin huachang ‘Golden Flower of Prosperit…

-

![Kwan Hsu (1913-1995)]()

Kwan Hsu (1913-1995)

Kwan Hsu arrived in Portland in 1964, a newly minted professor tasked n…

-

![La Grande]()

La Grande

La Grande, the seat of Union County, is nestled in the eastern foothill…

-

![Lan Su Chinese Garden]()

Lan Su Chinese Garden

Poetically named Garden of Awakening Orchids, Lan Su Yuan, the Portland…

-

![Lung On (1863-1940)]()

Lung On (1863-1940)

Lung On (Liang Guanying, also known as Leon) was a partner with Ing Hay…

-

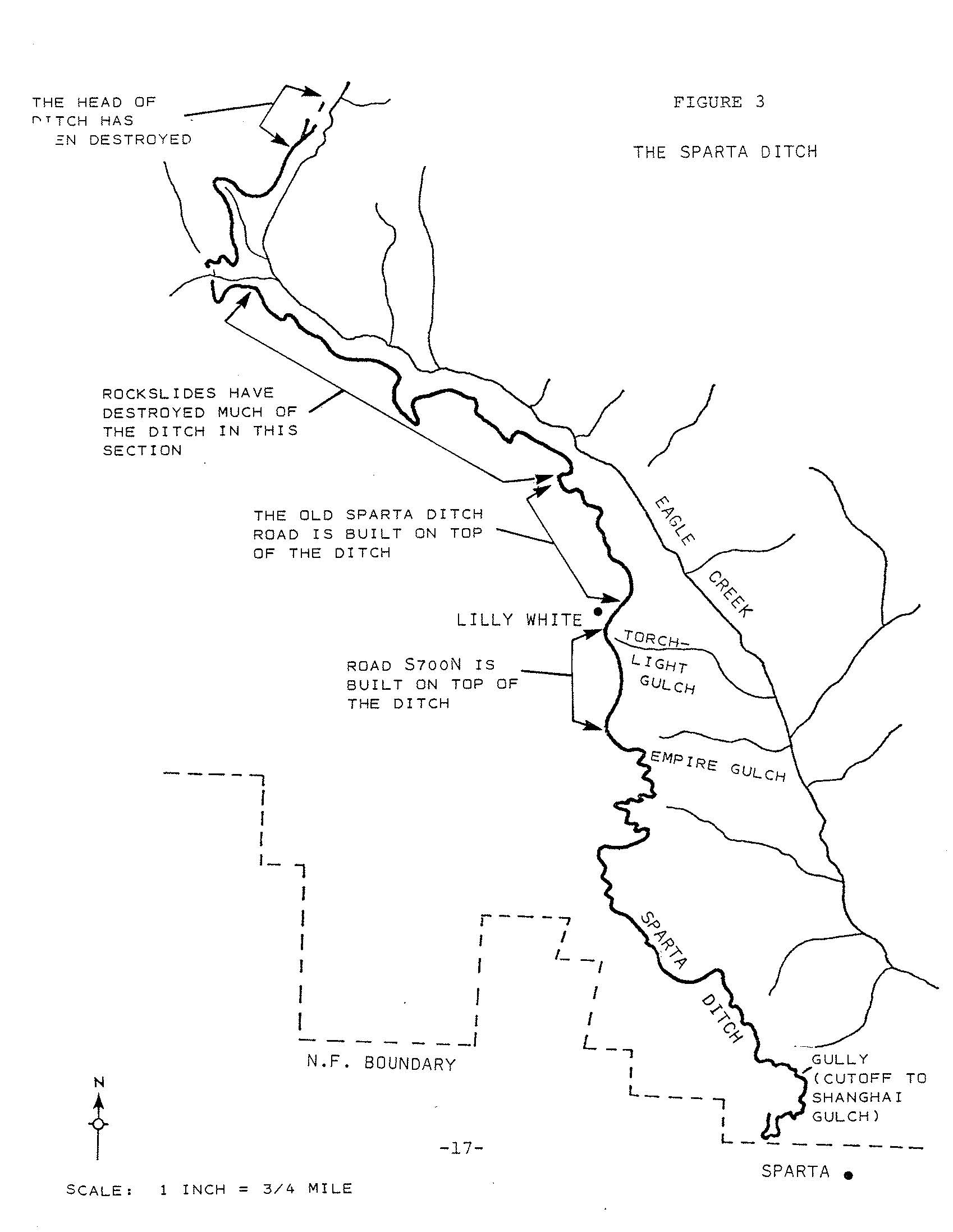

![Sparta ditch]()

Sparta ditch

The Sparta Ditch, a thirty-two-mile-long irrigation ditch straddling th…

-

![Two Dragon mining camp]()

Two Dragon mining camp

Two Dragon Camp was an isolated, 2.5-acre placer mining camp in the Cam…

-

![Waldo Building (Portland)]()

Waldo Building (Portland)

The Waldo Building (also known as the Waldo Block), on the corner of So…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Annals of the Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle: Chinese Historical Society of the Pacific Northwest, Western Washington University, 1984.

Dreams of the West, A History of the Chinese in Oregon, 1850-1950. Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, in association with the History Department of Portland State University. Portland, Ore.: Ooligan Press, 2007.

Chia-chi Ho, Nelson. Portland's Chinatown: The History of an Urban Ethnic District. Portland, Ore.: City Bureau of Planning, 1978.

Wong, Marie Rose. Sweet Cakes, Long Journey: The Chinatowns of Portland, Oregon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2004.